Now Playing: War-Gods of the Deep (aka City in the Sea) (1965)

Pros: Great production design, sets and costumes; Excellent cinematography.

Cons: The romantic leads are badly miscast; Comic relief featuring Herbert the rooster misfires; Underwater action scenes are overlong and plodding.

Special note: This post is part of the Vincent Price blogathon intrepidly hosted by Gill and Barry at the Realweegiemidget Reviews and Cinematic Catharsis blogs. Check it out for more priceless Price reviews and tributes than you can shake an Edgar Allan Poe tome at!

Allow me to make a bold statement. If in

Vincent Price's lengthy film career, his only appearances in the horror genre had been the handful of Edgar Allan Poe-inspired films for American International Pictures (AIP), he would still be regarded as one of the great horror stars.

But fortunately, horror fans can choose from a treasure trove of memorably chilling and sometimes campy (in a good way) performances, from the early Universal days of

The Invisible Man Returns (1940), to his horror break-out role as Prof. Jarrod in

House of Wax (1952), to the sci-fi horrors of

The Fly (1958) and

The Return of the Fly (1959), to the high camp of the Willam Castle films (

House on Haunted Hill,

The Tingler, 1959), and the even higher camp of his roles as Dr. Phibes (

The Abominable Dr. Phibes, 1971;

Dr. Phibes Rises Again, 1972) and Edward Lionheart, the hammy and deadly Shakespearean Actor in

Theater of Blood (1973).

Even in the lesser known, less successful horror films (

The Mad Magician, 1955;

Diary of a Madman, 1963;

Twice-Told Tales, 1963;

Cry of the Banshee, 1970, etc.), Price’s presence lent them a modicum of dignity and distinctiveness. Price had his work cut out for him in

War-Gods of the Deep (aka

City in the Sea), a film that came towards the tail end of AIP’s fixation on Poe as a marketing ploy, and one that really didn’t do the brand any favors.

With some of the AIP Poe films, the connection with the author’s works is tenuous at best. Previously, the company had slapped the title of a short poem,

The Haunted Palace (1963), on an adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft novella,

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. And

The Raven (1963) was a campy fantasy-comedy that was completely antithetical to the somber tone of the famous poem.

In the case of

War-Gods/City in the Sea, the producers decided to establish the film’s Poe credentials and set the mood by having Price recite select lines from the poem after the titles sequence (and at a couple of other points in the film). At the outset, things look promisingly spooky and atmospheric: it’s a dark and windy night, and a body has washed up on a rugged stretch of the Cornish seacoast.

|

"I'm just going out for a bit of fresh air, I'll be - Whoops! WHHAAAAAAA-A-a-a-a-a-h-h-h..."

KER-PLUNK! |

A visiting American mining engineer, Ben Harris (

Tab Hunter), helps the locals retrieve the body. When they identify it as Penrose, a lawyer staying at the nearby hotel (a converted mansion perched precariously atop a cliff), Ben elects to hike up to the place to let the proprietors know.

He meets the beautiful daughter of the hotel’s owner, Jill Tregillis (

Susan Hart), and in turn is introduced to an eccentric artist staying at the mansion, Harold Tufnell-Jones (

David Tomlinson). Harold’s constant companion is Herbert the rooster.

When Ben and Jill go to take a look at Penrose’s room, they hear noises inside. Ben surprises an otherworldly intruder who hurls some bric-a-brac at him and then escapes out a window.

Between the superstitious locals and Tufnell-Jones, Ben learns that the hotel and nearby village are the epicenter of strange happenings: weird lights seen in sea, the soundings of eerie ghost bells, mysterious disappearances, and bodies periodically washing up on shore.

Later that night, the strangeness escalates as Jill is grabbed by the intruder and the two disappear through a hidden door off of the study. Ben hears the commotion and in the darkness and confusion, mistakes Harold for the intruder.

Ben discovers seaweed on the floor and immediately concludes that Jill has been taken. With the help of Herbert the rooster, they discover the secret passageway and take off in pursuit (with Herbert along for the ride in a basket).

They descend into a large cavern, at the end of which is a whirlpool. Ben steps out onto a rock ledge to get a better look and promptly loses his footing. When Harold reaches out to help, all three are sucked into the swirling water.

|

| "When the innkeeper said they had a hot tub, I wasn't expecting this!" |

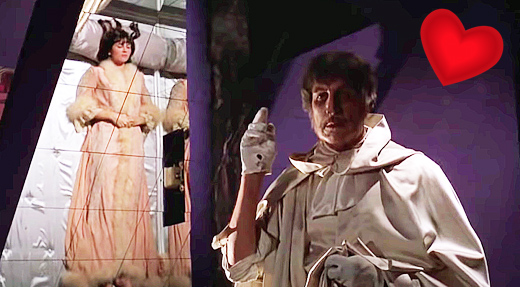

The whirlpool delivers them to the underwater lair of an imperious mystery man known as the Captain (

Vincent Price), where they are taken prisoner. Gradually, the Captain’s story is revealed: He and his band of not-so-merry men were notorious smugglers who, while fleeing from the authorities, stumbled upon an immense, ancient underwater city and made it their new home.

Like Atlantis, the city was built by an ancient civilization and eventually overtaken by the sea. The last remnants of that civilization have devolved into primitive gill-men who are most at home in the water, but who can also maneuver on land.

The Captain and his crew have been there for longer than they can remember. Air, heat and energy are delivered by immense pumps powered by a nearby underwater volcano. The Captain has convinced himself and his crew that the peculiar mix of atmosphere in their lair has suspended the aging process -- but if they were to expose themselves to the UV light on the surface, they would die of old age in seconds.

However, the volcano has become much more active, causing violent tremors, and the pumps are failing. The Captain has been sending gill-men to the surface to scavenge for scientific books, equipment, even people -- anything that might help in figuring out how to stop the volcano from erupting. When, after a recent raid of the hotel, the Captain discovered a sketch of Jill that Harold had made, he became convinced she was his long-lost wife, and had a gill-man kidnap her.

|

| "Ah, the volcano's really boiling over now -- anybody wanna make s'mores?" |

The Captain learns that Ben is an engineer, and gives him an absurdly short period of time -- a matter of hours -- to figure out how to save the city, or be drowned like the others who have outlived their usefulness. The landlubbers have their work cut out for them: find a way back to the surface before the volcano blows or the Captain decides they’re expendable. A rebellious member of the Captain’s gang and a doddering old clergyman who had been kidnapped decades before may hold the keys to their freedom.

Thanks to the early 1900s setting, the period costumes, and the gorgeous “Colorscope” widescreen cinematography,

War-Gods, especially at the beginning, looks like a worthy successor to AIP’s Roger Corman-directed Poe pictures. There’s a tongue-in-cheek homage to

House of Usher, as a decrepit man-servant at the old hotel escorts Ben by candlelight to see Julia. As thunder sounds in the background and they pause at the door to the study, the servant ominously warns Ben about the weird artist guest who has brought “the beast” with him. The beast turns out to be Herbert the rooster. Yikes!

From there, the film immediately doubles down on the “comic” relief. After introductions, Harold proudly shows Ben a full-length self portrait he’s done. Ben takes note of the acronym next to the artist’s signature:

Ben: “Harold Tuffnel-Jones, FRA. Oh, Fellow of the Royal Academy?”

Harold: “Not actually. Founder of the Roosters Association, very selective.”

And that's one of the high points of the alleged comedy.

Louis M. Heyward, then head of AIP’s London-based division, was responsible for the questionable comic relief. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver (

Science Fiction Stars and Horror Heroes: Interviews with Actors, Directors, Producers and Writers of the 1940s through 1960s, McFarland, 1991), Heyward remembered getting a call from

War-God's English producer (

George Willoughby), saying that the script was “impossible” and they couldn’t possibly shoot it.

Heyward’s boss

Sam Arkoff told him to fix the situation, and he ended up traveling to AIP’s studios in England to referee between feuding co-producers

Dan Haller and Willoughby. His ultimate solution was to rework the screenplay and add Herbert the rooster:

“The one thing I felt was missing was humor, and that’s where the chicken appeared. There was no chicken in the script, so I wrote it along with the David Tomlinson character. Tomlinson was enjoying great vogue at the time because he had just done Mary Poppins (1964) for Disney. At the point when the English producer saw that I had written in a chicken, and knew that whatever I wrote was going in, he quit -- he said, ‘I don’t do chicken pictures!’ And Dan Haller took over the reins.” [Weaver, p. 160]

|

| Herbert the rooster hitches a ride with Harold inside the Jules-Vernesque diving suit. |

One can certainly sympathize with Willoughby. While Tomlinson was a talented actor, his character’s relationship with Herbert is a tiresome distraction from the action, and a direct steal of Hans’ Gertrude the duck in 20th Century Fox’s

Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959).

While Poe’s poem may have furnished the title, the film’s real tribute is to Jules Verne. When Ben and Harold race through the secret passageway and find themselves in a huge underground cavern with stalactites, stalagmites, treacherously narrow stone bridges and a dizzying whirlpool, it feels like a scaled-down version of

Journey to the Center of the Earth. Then, when they end up in the Captain’s underwater lair, with its 19th century costumes and steampunk paraphernalia, there’s a definite Captain Nemo vibe going on.

It’s in the sets and production design that

War-Gods really excels. Heyward credited producer Dan Haller with coming up with some “awfully good” sets. [Ibid.] They provide an impressive otherworldly backdrop and make the film seem far more expensive than it was. Colossal statuary of ancient man-beast hybrids and hieroglyphics running the length of the walls create a phantasmagorical mix of ancient Egypt, Babylonia and some Lovecraftian temple of the Elder Gods.

Stephen Dade’s excellent widescreen cinematography also contributes to the sumptuous, decadent feel. Splashes of color from costumes, sets and the Captain’s steampunk equipment punctuate the deep shadows of the underwater realm. The photography is on par with the very best of the Roger Corman-directed Poe pictures.

|

| "Dang it! I told you we were going to be late for the new Survior auditions!" |

Unfortunately, the top-notch production values can’t compensate for the mediocre script or miscast actors. Vincent Price is of course the anchor for this ostensible Poe picture, but his character lacks the tragic depth of some of his other Poe roles, and he’s reduced to looking alternately imperious and pensive and barking orders at his men and the captives.

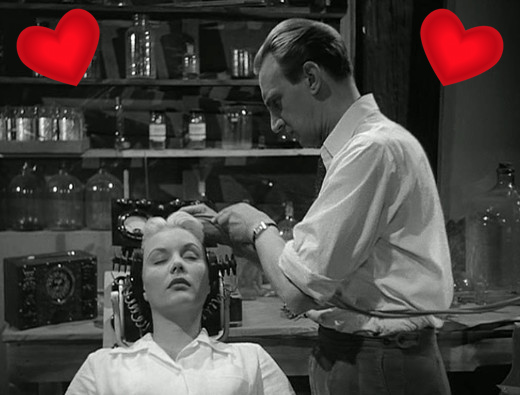

Tab Hunter and Susan Hart

look fine in their roles, but at various points Hunter looks like he’s about to burst out laughing, and Hart comes off like a high school thespian reading her lines for the first time. Tab and Susan had previously appeared in

Ride the Wild Surf (1964), a “teen” beach comedy from Columbia Pictures. One wonders what combination of chance circumstances and wheeling-dealing ended up scooping up two insouciant, all-American heartthrobs from the beaches of Hawaii and dumping them into the middle of an atmospheric, Gothic horror-fantasy.

David Tomlinson was still basking in the glow of a signature role in

Mary Poppins when he was tapped for

War-Gods. Despite his comedic talents, he flounders like a fish out of water in a role that was grafted, like a parasitical suckerfish, onto the production at the last minute.

|

| "Will she be all right? I told her this wasn't a surf picture, but noooo, she had to try out her new board!" |

The guiding hand of legendary director

Jacques Tourneur should have been a big plus for

War-Gods. There are flashes of the old Tourneur touch, such as Ben’s first encounter with the intruder at the hotel, in which the gill-man sticks to the shadows and we see only enough to get an impression of a bizarre, otherworldly creature. However, when the story switches to the underwater city, the action and suspense largely grind to a halt and are replaced by static shots of the Captain telling his backstory and the landlubber captives furtively conspiring with disgruntled underlings to escape.

AHOY MATEY, SPOILERS AHEAD! (SORT OF)

The climactic action that does take place is all underwater. The chase and fight with the gill-men is certainly ambitious, a sort of

Creature from the Black Lagoon meets

Thunderball. But the sequence is ponderous and poorly edited. The frequent intercutting of the action with close-ups of actors’ faces inside their Jules-Vernesqe diving helmets serves more to slow things down than to clarify who’s doing what to whom.

Worst of all, in the one sequence in which the gill-men finally get some healthy screen time (“Alright Mr. Tourneur, I’m ready for my close-up…”), the compromise between an effective-looking creature suit and one giving the stunt-men sufficient underwater maneuverability is starkly obvious. These are pretty poor cousins of the

Creature from the Black Lagoon, and a disappointing payoff for viewers wanting thrilling action and scary monsters after sitting through dull stretches of exposition.

|

"The Krusty Krab? Go straight past the volcano for about a half a league, then turn

right at Poseidon's Palace. You can't miss it!" |

This was Jacques Tourneur’s last film. While only in his early ‘60s, the industry had moved on, and according the Heyward, he was more than happy to get one more opportunity to practice his craft:

“Jacques was, again, at the nadir of his career, but he wanted to direct another picture or two. He was overly agreeable, and there was a sadness to that. At AIP, it was the same with directors as with actors. If you were a young director, AIP was giving you a chance; if you were an old director, your career was on its way down and we inherited you. You were usually afraid to fight because it would influence the next picture. But face Jacques with a technical problem and he would come up with answers. He knew his craft and his media.” [Weaver, p. 161]

On the other hand, Vincent Price was not done by a long shot. According to Price’s daughter Victoria, this film and an even greater stinker,

House of 1000 Dolls (shot in Madrid in 1967), soured him on AIP. But Vincent had too many interests and too many irons in the fire to let a few cheesy B pictures get him down:

“Although my father was in despair about the sorry run of films he was being forced to make, at the same time he was in the most visible and popular era of his career. As an actor in his mid-fifties, he did not take his growing appeal for granted, and from judging the Miss American Pageant to appearing as Grand Marshall of the Santa Claus Parade in Hollywood, he brought grace and charm to every event with which he was associated.” [Victoria Price, Vincent Price: A Daughter’s Biography, St. Martin’s, 1999, p. 260]

War-Gods doesn’t come close to scraping the bottom of the barrel the way

House of 1000 Dolls did. It’s an ambitious sci-fi-horror-fantasy that at least looks more expensive than its budget. But it’s done in by a weak script made even weaker by forced comic relief, and a couple of egregiously miscast romantic leads.

It appeals more for its curiosity factor: as Jacques Tourneur’s last feature film, and as that AIP Poe film that everyone forgets. But hey, if you really like chickens, this one might be right up your alley!

|

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.

-- Edgar Allan Poe, The City in the Sea |

Where to find it: try here for the

DVD; or stream it (for now) on

Youtube.