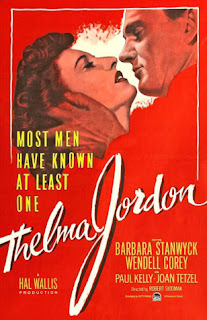

Pros: A good, mid-level effort that represents a sort of watershed in Barbara Stanwyck’s noir career; Features a relatable “everyman” in Wendell Corey

Cons: A head-slapper of an ending that manages to be both brutal and cloyingly sentimental

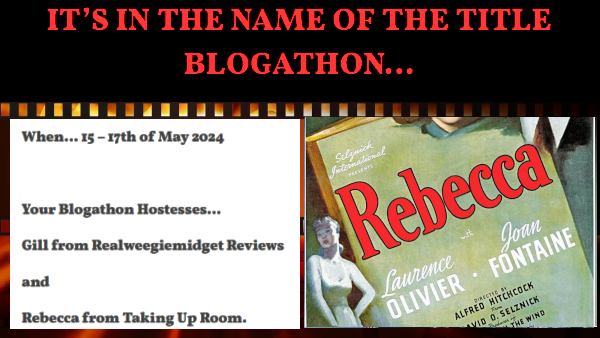

This post is part of the It’s in the Name of the Title Blogathon, hosted by two big names in movie blogging, Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews and Rebecca at Taking Up Room. Gill and Rebecca tasked their fellow bloggers with reviewing a movie in which a character’s name (first, last or full) appears in the title; for more contributions, see either or both of the hosts’ blogs.

Speaking of big names, there weren’t many that were bigger in the classic era of screen entertainment than Barbara Stanwyck. From the risque pre-Code talkies in which she played plucky women of questionable virtue, to TV dramas like The Big Valley where she portrayed tough-as-nails matriarchs, Stanwyck blazed her own distinctive cinematic trail, eventually garnering four Best Actress Academy Award nominations, an honorary Oscar, three primetime Emmys and a multitude of lifetime achievement awards, among other honors.

A rundown of Stanwyck’s title roles alone demonstrates the depth and variety of her career: as Mexicali Rose (1929) she’s a “loose” woman who likes to use men; as Annie Oakley (1935) she can do anything a man can do, and better; as harried, working class Stella Dallas (1937), she would do anything to help her daughter get ahead in life; as The Mad Miss Manton (1938), she’s a fun-loving debutante who proves to be more adept at discovering clues than the police; as Martha Ivers (The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, 1946), she’s an intimidating business woman with a dark secret; and as Mrs.Carroll (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, 1947), she’s the new wife of a tortured artist who may or may not be utterly mad.

Stanwyck reached her noir femme-fatale peak as cold-as-ice Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (1944). But as the war years receded and America settled down into a dull but comfortable suburban existence, Stanwyck’s screen image shifted. The noir roles were still there, but she was just as likely to be on the receiving end of dark designs as not.

|

| Fred was sorry that he wasn't double indemnified against laser death stares. |

Only a year after her dicey stint as the second Mrs. Carroll, Stanwyck was again in peril in Sorry, Wrong Number, portraying an invalid, Leona Stevenson, who inadvertently overhears a murder plot from her bedroom phone.

The difference between calculating Phyllis Dietrichson and panicky, bed-ridden Leona couldn’t be more stark, yet when Thelma Jordon rolled around in 1949, Stanwyck’s crime drama roles -- both as the Femme Fatale and the Suffering Woman -- were starting to get on her nerves:

“‘My God, isn’t there a good comedy around?’ [Stanwyck] asked at the time. ‘I’m tired of suffering in films. And I’ve killed so many co-stars lately, I’m getting a power complex!” [Quoted in Dan Callahan’s biography, Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman, University Press of Mississippi, 2011, p.159]

As if to punctuate the grimness of the roles she was getting, Thelma Jordon is both a femme fatale and a sufferer. Thelma takes a long, circuitous route to get to both states of noir-ness (maybe too long and too circuitous; more on that later), and drags a noir Everyman in the form of Assistant District Attorney Cleve Marshall (Wendell Corey) along for the ride.

Fate arranges for a “meet cute” between the duplicitous Thelma and her ostensible patsy, DA Marshall. One night at the District Attorney’s office, Cleve is downing shots and complaining about his depressing marital situation to his boss, Miles Scott (Paul Kelly). After Scott calls it a night and goes home, alluring Thelma shows up at the office asking for Scott, wanting to report an attempted burglary at her aunt’s house, where she is staying.

Now inebriated and not wanting to go home where his wealthy, domineering father-in-law is holding court at a dinner party, Cleve convinces Thelma to go out for drinks. Pretty soon Cleve, disenchanted with his hum-drum middle class life, falls hard for the alluring and mysterious Thelma.

|

| Cleve: "I'm fed up. Ever heard that phrase? No, you wouldn't, you're not married." |

It seems that a combination of alcohol and infatuation has painted a big P for Patsy on Cleve's forehead.

First, there’s Thelma's story about attempted burglaries at her aunt’s house that smells to high heaven. When asked why she didn’t just go to the police, Thelma responds with a laugher of an explanation that her aunt is afraid of uniformed cops. Then, having allowed Cleve to think that she was single, Thelma belatedly admits that she herself is married -- to a low-life crook and con man named Tony (Richard Rober).

The noir stuff soon hits the fan when, on the night that the pair are planning to go off together on a romantic trip, Thelma calls Cleve in a panic that her aunt has been shot. Cleve steals over to the house to help clean up the mess. Wanting desperately to believe that it’s Thelma’s no-good hubby Tony who has shown up unannounced and killed the old lady in an attempt to rob her, Cleve, with his extensive DA experience, frenetically barks orders at Thelma to set the scene to look like a garden-variety burglary gone wrong.

If Thelma is truly a cold-blooded murderer she’s an excellent actress, as she seems genuinely panicked, like an innocent bystander who realizes how much the circumstances make her look guilty. And despite the lovers’ best efforts at rearranging the crime scene, she most definitely looks guilty.

|

| Thelma: "I wish so much crime didn't take place after dark. It's so unnerving!" |

When Thelma’s sketchy past becomes public, along with the news that Aunt Vera changed her will in Thelma’s favor, means, motive and opportunity line up against her. Combined with Vera’s butler’s testimony about Thelma’s furtive behavior on the night in question, DA Scott decides that a murder charge is a slam dunk.

With the ball in his court, Cleve goes to work, anonymously suggesting to Thelma’s lawyer (Stanley Ridges) that he hire the Chief District Attorney’s lawyer brother to work for the defense, forcing the DA to step down due to conflict of interest. Cleve gets the lead prosecutor assignment, and proceeds to do everything he can to throw the case.

Is he the dupe of a cold-blooded Phyllis Dietrichson type, or is it more complicated than that? And where was the shadowy Tony on that fateful night?

The File on Thelma Jordon invites the viewer to be an alternate juror on the case. We haven't witnessed the actual shooting, but we have seen Cleve’s and Thelma's hurried rearrangement of the crime scene. The circumstantial evidence -- like the convenient change to the will -- is strong, but there are seeds of doubt. Thelma’s distress on the night of the shooting seems genuine, which is uncharacteristic of a shrewd, heartless manipulator -- or was she just acting?

Stanwyck synthesizes Thelma’s contradictions over the course of the film, from wry bemusement at Cleve’s drunken advances, to smoldering passion, to panicked helplessness in the middle of the night, to tight-lipped stoicism after she’s been arrested, to an almost regal dignity as she leads a swarm of reporters and onlookers from the jail to the courtroom to hear the jury’s verdict.

|

| You'd be confident too if you had both the defense and the prosecution on your side. |

Thelma’s ultimate fate comes completely out of left field and it’s both shocking and cloyingly sentimental. It's the sort of ending guaranteed to bring a tear to the eye of any blue-haired upholder of public morality.

Fortunately, Thelma's ending hasn't erased fond memories of the film. Biographer Dan Callahan relates that at the American Film Institute’s fete of Stanwyck, in which she received a Lifetime Achievement Award, Walter Matthau singled out Barbara’s performance in Thelma Jordon:

“[P]articularly the way she sighed, ‘Maybe I am just a dame and didn’t know it.’ Matthau then went on to knock her co-star, Wendell Corey, an unprepossessing actor who was good when he was doing a menacing type in Budd Boetticher’s The Killer is Loose (1956), but who was hard-pressed to hold his own as a leading man opposite Stanwyck.” [Callahan, p. 158]

While I’m hesitant to disagree with the great Walter Matthau, I think “unprepossessing” is just what the film calls for. Cleve is a post-war, suburban “everyman” who is fed up with domestic life and resents being dominated by his overbearing father-in-law. Cleve would be far less believable in the hands of a more charismatic leading man who could “hold his own” with Stanwyck. Men like Cleve don’t often score with sensual mystery women like Thelma, and it makes sense that he’s willing to endanger his family and career for her.

|

| Thelma: "I'm no good for any man for any longer than a kiss!" |

In the same year as Thelma Jordon, Corey lost Janet Leigh to Robert Mitchum in Holiday Affair. Corey was the epitome of the reliable but unexciting second male lead who loses out in romance to the charismatic star. At least he had Stanwyck all to himself for most of The File, even if it wasn’t entirely due to his animal magnetism.

The File on Thelma Jordon was directed by Robert Siodmak, who was one of a generation of filmmakers who got their start in Germany during the silent era, but fled to Hollywood as Hitler rose to power. In the 1940s he made a string of crime pictures that years later would come to be seen as some of the very best examples of film noir, including Phantom Lady (1942), Christmas Holiday (1944; with Deana Durbin and Gene Kelly), The Killers (1946; Burt Lancaster’s film debut and Ava Gardner’s first featured role), Cry of the City (1948; Victor Mature and Richard Conte), Criss Cross (1949, Burt Lancaster and Yvonne DeCarlo), and of course The File on Thelma Jordon to round out the decade.

Besides having such an assured director in her corner, Thelma benefits from George Barnes’ standout cinematography. Many of Cleve’s and Thelma’s scenes together take place at night, with the play of light and shadow serving as a visual metaphor for the lovers' dark sides and conflicting emotions.

Thelma Jordon is not Barbara Stanwyck’s best title role, and it’s not the high point of director Siodmak’s noir career, but it is a solid crime thriller with a relatable everyman in the person of Wendell Corey and enough plot twists and turns to make things interesting. But be forewarned: the slap dash ending might induce cognitive whiplash.

Where to find it: Streaming | DVD

|