Pros: A low-budget sci-fi thriller that masterfully builds suspense, respects its audience and features solid performances

Cons: Fans of CGI and big budget effects won’t find much to like

Thanks to everyone who has participated in the ‘Favorite Stars in B Movies’ blogathon! This post on Maureen O’Sullivan is my contribution to the effort. If you haven’t already, please explore all the other marvellous posts on famous film stars and their B movie appearances: Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3

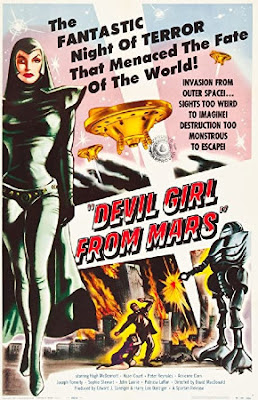

I have reminisced many times here at Films From Beyond about my Monster Kid days, before the internet era and streaming, before VCRs and time shifting, and even before the advent of basic cable.

Yep, it was just me and the family’s black and white console TV with the rabbit ears antenna that brought in 3 clear channels and maybe another fuzzy one on a good day. But, as an eager young member of the Monster Kid Club, that was good enough. At the height of those salad days, growing up in a small university town in the midwest, I was in TV reissue/syndication heaven.

On Friday nights I had my ‘50s sci-fi movies (broadcast from the big city station 30 miles to the south), and on Saturday nights I eagerly watched the classic monsters (broadcast from the university station in my hometown). While weekend nights generally belonged to the monsters, there were plenty of opportunities to catch family friendlier, but still watchable, action-adventure movies on a number of TV movie matinees (not to mention the local downtown theater).

The Tarzan movies starring former Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller were among the more memorable offerings on those lazy weekend afternoons. Sure, Tarzan was no Frankenstein, Dracula or Wolf Man, but there were enough thrills and chills in those movies to get my 10 year old heart beating just a little faster. (There were even monsters here and there, like the time Boy was trapped in a giant spider’s web in Tarzan’s Desert Mystery).

Speaking of hearts beating a little faster, beautiful Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane Parker joined Weissmuller for a decade-long run in six of the MGM Tarzan films, starting with Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932 and ending with Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942). The skimpy outfits she wore in those films revealed as much skin as ‘30s audiences were ever likely to see (or for that matter, naive ‘60s TV viewers during the height of Tarzan’s syndicated popularity). O’Sullivan undoubtedly was the first movie crush for thousands (if not a whole generation) of fans (and yes, I was a member of that legion).

In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, O’Sullivan had a good laugh over the fan mail she received as a result of the Tarzan costumes:

"[Weaver:] In the earliest Tarzan movies, your wardrobe was very skimpy. Did that make you self-conscious at all?

[O'Sullivan:] I didn’t think it was so skimpy. What was it now, I’ve forgotten… the outfit torn up the side? No, I thought it was appropriate for where I was. It wouldn’t have been appropriate to wear at Buckingham Palace, or to church or something [laughs], but it was appropriate for what I was doing. So no, it didn’t worry me at all -- until I started getting mail about it. And I thought, 'Well, people are crazy. They have to write about something.' If they didn’t write about that, then they wrote about how they liked me -- it was one thing or the other. I did get a lot of mail on my costume and I thought, 'Do people really have nothing to do except write to strangers?' [Laughs]" [Tom Weaver, I Was a Monster Movie Maker, McFarland, 2010, p. 185]

Fortunately, the talented Miss O’Sullivan got roles that required more than just baring her legs and keeping Tarzan out of trouble. Even as her mailbox was filling up with fan letters appreciative of her jungle wardrobe, she was donning elaborate period costumes in such prestige films as The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934), David Copperfield (1935) and Anna Karenina (1935).

After the last Tarzan film in 1942, O’Sullivan took a break from acting to devote time to her husband, writer/director John Farrow, and her growing family (ultimately having seven children, six of whom -- including Mia Farrow -- went on to work in movies and TV).

Upon returning to acting in 1948, O’Sullivan made a splash in a starring role opposite Ray Milland in the film noir classic The Big Clock. Several undistinguished B movies later, O'Sullivan settled into guest shots on TV shows and theater appearances until she played an alcoholic show business mother to her real life daughter Mia Farrow in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986).

While Hannah and Her Sisters and the obscure, low-budget sci-fi drama Stranded (released a year later) might seem to be worlds or even universes apart, they both share the theme of families weathering adversity.

In Stranded, O’Sullivan’s movie family is a small one. She plays Grace Clark, an elderly but scrappily independent woman living with her granddaughter Deirdre (Ione Skye) in a farmhouse on the edge of town (later on we learn that Deirdre’s parents were killed in a car crash).

On a dark and stormy night, what seems at first like a lightning hit that takes out the power instead turns out to be a weird energy beam that has delivered something very strange to the Clark house. Deirdre and Grace, who are upstairs, notice a weird blue light shining from the parlor on the ground floor. Grace bravely grabs a shotgun to confront the intruders, but when it becomes apparent these are no garden variety burglars, Grace and Deirdre hide in a bedroom.

|

| Alien travel advisory: In the U.S. there are more guns than people, so exercise caution! |

A tense situation turns tragic when Deirdre’s would-be boyfriend Jerry (Kevin Haley) and his dad Vernon choose exactly the wrong time to stop by the Clark house on their way home from a fishing trip. When no one responds to his calls from the darkened house, Jerry gets worried and grabs a gun from the glove compartment.

Instead of finding Deirdre and Grace, Jerry and Vernon are startled by a tall humanoid figure with long white hair standing in the parlor, a glowing blue crystal hovering in front of her. A weird gnome-like humanoid suddenly jumps up and hisses, and before you can say “guns and surprise alien visits don’t mix,” a panicked Jerry shoots the tall figure. In turn, another figure at the top of the stairs blasts Jerry with some sort of energy beam, sending him flying out the front door. Vernon, grief-stricken and vowing revenge, drags his son’s body back to the truck and hightails it out of there.

|

| The only thing Deirdre and Grace have to fear is fear itself. |

When things get quiet, Deirdre and Grace tiptoe down the stairs, lamp and shotgun in hand. The creature that blasted Jerry suddenly intercepts them in the hallway, grabbing Grace’s shotgun and then herding them into the front parlor.

The sight that greets them is surreal: The gnome creature and two other slender, pale humanoids with high foreheads and long, flowing hair are huddled around their stricken companion who is lying on the floor. They look like they could be a family -- one of the uninjured aliens is a young, almost androgynous-looking male, and the other is older, with a stiff, regal bearing. Grace whispers, “They almost look like angels!”, to which Deirdre responds “I don’t think so…” The film’s credits list them simply as Prince (the young alien; played by Brendon Hughes), Sir (Dennis Vero) and Queen (the gunshot victim played by Florence Schauffler).

|

| Surprise alien visits and guns don't mix. |

There’s alien-looking, and then there’s alien-looking. In the latter category is the short, squat gnome with a huge creased dome of a head and long whiskers growing out of the bottom of his chin-less face (played to great effect by Michael Balzary, aka Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers fame). The creature seems more like a humanoid pet to the aliens, and just wants to please. After the initial shock, Grace takes to the adorably homely creature, dubbing him “Jester.”

But most alarming is the creature that seems to be the alien family’s bodyguard. Despite having female curves, Warrior (Spice Williams-Crosby) is malevolent-looking, dressed in a form-fitting suit (or is it her skin?) and is mostly faceless with the exception of two large, glowing eyes (not to mention the deadly energy-beam weapon she wears on one arm).

|

| This is not something you want to see in your house at night. |

Meanwhile, the aliens and the Clarks are attending to the mortally wounded Queen. Grace deescalates the tense situation, exhibiting clear concern for the alien she calls “dear lady,” saying they need to get her to a hospital (Deirdre patiently explains to her grandmother that “they can’t go to a hospital.”) The Queen passes a brightly glowing blue crystal to Prince before expiring (Sir doesn’t seem to be in the line of succession -- you have to wonder if he’s the Prince Andrew of this royal alien court).

And before you can say “gee, that’s a surprisingly quick response time for a rural area,” multiple Sheriff’s squad cars are pulling up to the house. Even before the sheriff himself (Joe Morton) has had a chance to arrive, Vernon, with nothing but bloody revenge on his mind, goads one of the deputies to seize the day, with predictable results -- the deputy is zapped to death by Warrior, who is only defending her group.

When Sheriff McMahon finally arrives, he realizes he has inherited a cluster-you-know-what, with a dead deputy on the grounds, Deirdre and Grace bewilderingly shouting from the house that they’re not in danger, and deputies who are either too spooked to think straight or are ready to charge the house like brain-dead Rambos.

As if that situation wasn’t bad enough for a newly installed African American sheriff, a caravan of Vernon’s redneck buddies arrive just itching to blast them some aliens to kingdom come. The coup-de-grace is the sudden appearance of a solitary federal agent, Helen Anderson (Susan Barnes), complete in trenchcoat, warning McMahon that if he doesn’t quickly get control of things a military “clean-up” team will do the work for him. It just isn’t his day.

|

| Guns and angry mobs really don't mix. |

The best thing about Stranded is that the people behind it realized they didn’t have the budget to make something even remotely resembling Star Wars, so they settled for good writing, believable characters and solid performances. Not only that, but they decided to respect the intelligence of their audience.

For something so low-budget and small scale (just a single location), the film manages to pack a lot of suspense and unease (as well as pathos) into the proceedings. Much is left to the imagination. The visitors don’t arrive in a conventional spaceship, but rather some sort of transporter beam/wormhole that is never explained (and doesn’t need to be).

The aliens don’t speak English, nor is there a convenient Star Trek-style autotranslator. They are mute through most of the film (the implication being that they communicate telepathically), so the actors portraying them have to rely on facial expressions and gestures. Most expressive of all is Jester, the aliens’ “pet,” who wears his simple emotions on his sleeve, so to speak. The “angelic” aliens are a mix of the uncanny (human-looking, yet somehow not), a royal-like reserve, and gentleness.

The visitors’ backstory is communicated first to Deirdre through a series of telepathic images (aided by the blue crystal manipulated by the Prince). The rapid-fire succession of other-worldly images tells a tale of the aliens’ imprisonment, and a daring escape and pursuit by mysterious captors who aren’t shown in their entirety -- just their repulsive, reptilian legs. The sequence is simple and imaginative without requiring expensive effects or indulging in extraneous exposition.

|

| Who needs Star Wars-style holograms when you can just beam what you want straight into somebody's mind? |

Somehow, in a cosmic stroke of luck, the escapees managed to beam themselves to just about the only farmhouse in rural America where intruders -- especially such weird-looking ones -- wouldn’t be shot on sight. With their own history of tragedy and loss, Deirdre and Grace aren’t about to greet visitors, especially “angels,” with shotgun blasts.

As a result of their forbearance, Deirdre is given a telepathic glimpse of worlds no human has ever seen before -- not to mention forming a proto-romantic attachment to the angelically handsome Prince -- and Grace forms her own special bond with the alien goofball Jester. But with rival alien assassins on their trail and uncomprehending police with guns encircling the house, the peace won’t last long.

|

| It's the Clarks and their alien visitors against the world (and part of the universe). |

Joe Morton as Sheriff McMahon is in a position where, as the new sheriff in town (and an African American one at that), he is made to feel somewhat like an alien intruder in a rural area where racism is still rampant. In his confrontation with the would-be lynch mob, Vernon keeps calling the sheriff “boy,” but McMahon maintains his cool, and his deputies back him up, forcing the mob to back down.

In another example of coolness under pressure, McMahon enters the house to size up the situation and possibly negotiate what looks like a hostage situation. With Deirdre’s encouragement, the aliens give him the same telepathic briefing through the crystal. Outside the house, federal agent Barnes, who has some sort of hidden agenda of her own, suggests to the chief deputy that the aliens are using mind control on the sheriff, and that he needs to be prepared to take charge. With friends like these…

Interestingly, just a few years before, Joe Morton played the title role in the cult hit The Brother from Another Planet (1987), in which he was the alien being pursued by extraterrestrial bounty hunters.

|

| Joe Morton has a moment of sci-fi-induced deja-vu. |

Stranded was only the second movie role for UK-born Ione Skye (daughter of ‘60s pop-rock singer Donovan), who debuted in the gut-wrenching River’s Edge (1986). Although she is still working, the height of Skye’s career came with her appearance in one of the great coming-of-age comedies, Say Anything (1989), opposite John Cusack.

On the career flip side, Stranded was the second to last feature film Maureen O’Sullivan made (not counting three TV movies and a series guest shot). With the Grace Clark role O’Sullivan proved she hadn’t lost any of her acting chops, as she seemed to effortlessly combine a bit of steely resolve, a bit of elderly naivete, and a lot of empathy. Perhaps her best scene in Stranded is at the end credits, which are superimposed over footage of a local TV reporter interviewing Grace and Deirdre about their amazing alien encounter. O’Sullivan is completely natural and even a little impish in answering the reporter’s questions. It’s a delightful scene.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the other, behind-the-scenes talents that contributed to this stand-out (but highly neglected) sci-fi drama. Jeffrey Jur’s cinematography is exceptional, making expert use of light and shadow, and avoiding the overly dark, muddled night photography characteristic of other low-budget films. Subtly, the early scenes with the aliens -- when it’s not clear if they're dangerous or not -- are tinged with red, and then gradually, as they gain the trust of Deirdre and Grace, calming blues take over.

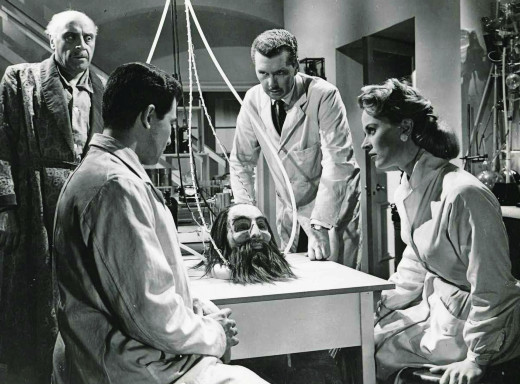

The alien design and make-up (credited to Vera Yurtchuk and Brian Wade) is simple yet effective. The Prince and his family seem to be inspired by the Nordic aliens of UFO lore. Warrior looks to be wearing a modified wetsuit, but the large eyes that dominate an otherwise featureless face make her very intimidating. Much less intimidating is Jester, who looks like he could be a cousin to the Ferengi, who were introduced in Star Trek: The Next Generation around the same time.

|

| Separated at birth? Top row: Nordic aliens and the Prince. Bottom: a Ferengi and Jester |

According to IMDb, director Fleming B. Fuller only directed two other feature films and one TV movie. Stranded is a solid sci-fi thriller that masterfully ratchets up the suspense, stimulates the imagination, and delivers some very good, affecting performances. I don’t know Fuller’s story, but it seems a shame he didn’t do more.

Where to find it: A soft-looking, but still watchable stream can be found here.

.jpg)