“[T]o my way of thinking, I never made a “B” movie in my life. The B movie dated from the Depression and was a phenomenon only through the early 1950s. … Everyone knew which movies were which; the studio publicity and production lists openly distinguished A’s from B’s Also, B movies earned only flat rentals on the second half of a double bill. … [T]he B’s had died out by the time I began directing.” [Roger Corman with Jim Jerome, How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, Da Capo Press, 1998, p. 36]Corman biographer Beverly Gray adds that early on, Corman prefered the term “exploitation films” -- he was always very willing and able to exploit the latest headlines and fads -- but that later, as the success of Star Wars and The Exorcist helped boost sci-fi and horror into big box office gold (with matching big budgets), he settled for the gentler term “genre films” to describe his low-budget output. [Beverly Gray, Roger Corman: An Unauthorized Biography of the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking, Renaissance Books, 2000, p. 48]

For the record, and with all due deference to the historical origins of the term and Roger’s insistence that he never made a “B” movie, we at Films From Beyond use the term “B movie” in its broader meaning, efficiently summarized at Wikipedia as “a low-budget commercial motion picture that is not an arthouse film.” (Interestingly, the first illustration on the page is a poster for Corman’s The Raven from 1963!)

Whatever you call them -- B movies, exploitation pictures, genre films, or independent films -- there’s always been a simmering tension between audience expectations of thrills and chills and the ability of B movie makers to deliver the goods on a low budget.

In the good ol’ days before sci-fi became big box office business, genre filmmakers like Roger Corman could get away with tiny budgets that could only accommodate a handful of effects artists at most (versus the literal armies of artists and technicians required today). You could also make a film with an original story and still expect to make money -- the 800 pound gorilla franchises like Stephen King, Star Wars and the MCU that could crush or shove aside anything else in their genres didn’t exist yet.

But you still had to be tuned into the cultural zeitgeist to keep your B movie gravy train chugging along. Especially in the early days, there were none better at it than Roger Corman. Like a financial wizard, he seemed to know just when to jump into a particular market and when to get out of Dodge.

War of the Satellites, released in 1958 in the midst of the panic over the Russians beating the U.S. into space, is a prime example of Corman’s ability to quickly capitalize on sensational headlines. In J. Philip di Franco’s The Movie World of Roger Corman (1979), the B movie King reminisced about his own contribution to the space race:

“War of the Satellites is an example of producing very, very rapidly. The first Russian Sputnik had been launched. A friend of mine, knowing I worked very rapidly, called me and said he had within the hour constructed a story line and was I interested. After I heard the story, I called Steve Brady, president of Allied Artists, and I said I could be shooting the picture in ten days and cutting it in three weeks. In roughly two months we could release the first picture about satellites. He said, ‘Done, we’ll do it.’” [di Franco, ed., pg. 16; see my review of War of the Satellites elsewhere on this blog.]Roger’s nimbleness and ability to work quickly and cheaply was very attractive to film companies desperate for a steady stream of new releases to satisfy the voracious youth market. Beginning in the late ‘50s and through much of the ‘60s, Corman was American International Pictures’ (AIP; formerly American Releasing Corporation) go-to guy. As described by biographer Beverly Gray, it was a neatly crafted, mutually advantageous partnership:

“Once he proved he could deliver the goods, he was soon making multiple AIP features a year … Upon delivering a completed film, he would receive $50,000 as a negative pickup fee, plus a $15,000 advance on the projected foreign sale. Though he was also guaranteed a percentage of the movie’s eventual profits, Corman never counted on this potential income. His strategy was to come in under $65,000 per film, so as to have working capital for his next project. The fact that he would plan every third or fourth feature to be ultralow-budget (below the $30,000 range) would help ensure a healthy profit in the long run.” [Gray, pp. 48-49]

|

| Show of hands: how many of you had a cool mom who let you order junk like this? |

As varied, action-packed and eccentric as Corman’s movies were during the period, their marketing, especially the posters, were on another level entirely. In a recent post on duplicitous advertising, I highlighted a couple of posters for early Corman quickies that egregiously exaggerated monsters that turned out to be less than awesome in the films themselves

Over-the-top exaggeration or downright deception often proved to be the rule, rather than the exception, especially with AIP’s practice, perfected by co-founder Jim Nicholson, of coming up with a marketing plan, including poster art, before the script was even completed.

|

| Do you dare reveal the monster lurking behind the poster? |

The films represented by the posters below all involved Roger Corman in some capacity, either as producer, director or both. For a couple of them he worked with his brother Gene, who was an accomplished producer in his own right. And just like my previous post on deceptive movie posters, these illustrations employ the special un-patented Reveal-O-Rama technology -- simply click on the poster to reveal the actual movie monster that was misrepresented in the art or hidden altogether!

|

| Aka "Attack of the Giant Leeches," 1959. The monsters in this one were actors wearing black plastic wet suits with suckers sewn on. Click the poster to see what they looked like on film! |

|

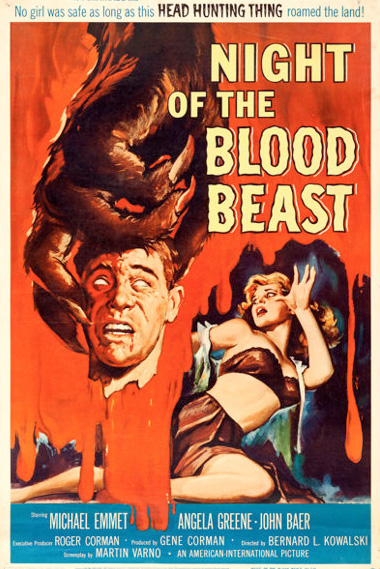

| Brother Gene produced; Roger was an uncredited executive producer. Gotta admit, this one creeped me out when I first saw it. It's an ultra-low-budget combo of From Dusk Till Dawn and Alien. See my review here. |

|

| This looks more like a poster for a genteel English comedy -- as a kid, I wouldn't have looked at it twice. Fortunately, I discovered Seymour and Audrey via late night TV. |

|

| This was also produced by Gene Corman with Roger serving as executive producer. The excessive poster promised far more than the film dared to deliver. On the other hand, it's the very first (and only?) film to feature a male astronaut impregnated with alien babies. Yeesh! See my review here. |

|

| There is a creature in the film that slightly resembles the thing in the poster. It's a kind of forerunner of the facehugger in Alien, and makes a memorable, gross-out appearance in the movie. |

|

| Because the term was plastered all over the news when the film came out, the manned spacecraft in it are referred to as "satellites." Richard Devon plays an alien who can assume human form and replicate himself as needed. See my review here. |

|

| Susan Cabot plays a cosmetics executive who tests an experimental anti-aging formula on herself and becomes a voracious monster. Kind of like Gwyneth Paltrow, except not as scary. |