Pros: At various points the film pays effective homage to classic vampires as well as contemporaneous ones like The Night Stalker.

Cons: Logic lapses and lack of sufficient backstory lead to confusion over characters’ actions and motivations.

I was sad to see the news of actor William Smith’s passing on July 5, 2021 at the age of 88. Although he made a long career out of playing bad guys, I first got to know Smith as Joe Riley, one of a trio of Texas Rangers (rounded out by Neville Brand and Peter Brown) led by the perpetually exasperated Capt. Parmelee (Phillip Carey) in the TV western Laredo (1965-67). Laredo was exciting and fun and didn’t take itself too seriously, and was right up there with The Wild, Wild West as my favorite TV western growing up.

The next time I encountered Mr. Smith, he had donned an eye-patch and a venomous disposition as Falconetti, poor man Tom Jordache’s (Nick Nolte) relentless nemesis in the TV mini-series Rich Man, Poor Man (1976). The memorable part solidified Smith’s status as one of Hollywood’s most reliable, go-to villains.

There were few better suited to tough guy roles than Smith. He was a lifelong bodybuilder, amassing world armwrestling championships, Air Force weightlifting championships, and dozens of amateur boxing wins in between acting gigs.

|

| The Good, the Bad, and the Toothy. William Smith as (L to R): Joe Riley in Laredo, Falconetti in Rich Man, Poor Man, & James Eastman in Grave of the Vampire |

But his tough guy exterior hid a brilliant mind. Smith became fluent in five languages, including Russian, which led to high government security clearances and hush-hush assignments while serving in the military. He was working on a Ph.d. when the acting bug bit hard in the form of an MGM contract. [Wikipedia.]

Smith got his acting start as a child in the ‘40s, appearing in mostly uncredited roles starting with The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), and then, in quick succession, a number of films that would become memorable classics: The Song of Bernadette (1943), Going My Way (1944), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), Gilda (1946), and The Boy with the Green Hair (1948).

By the 1960s, he was bouncing from one TV show to another, flexing his muscles and acting chops in all kinds of genres. By the late ‘80s the TV shows petered out, but offers of tough guy/villain roles in B movies (and frankly, some C, D and Z-grade flicks as well) kept him busy right up to the 20-teens. (Smith is at his B-villain best in the offbeat sci-fi-action-thriller-comedy Hell Comes to Frogtown, 1988; see my review here.)

In perusing Smith’s IMDb credits, I stumbled upon a familiar title, Grave of the Vampire from 1972. I’d long been aware of Grave for its unique premise: that vampires can be born as well as made -- in this case, as the result of a rape (!!) by a centuries-old vampire.

Grave of the Vampire has been in the public domain for sometime, with a long history of home video releases by Mill Creek, Alpha Video and Scream Factory, among many others; it’s also available on the Internet Archive and YouTube. Even so, I somehow managed to avoid seeing it until now.

Grave is one of the few out-and-out horror films on Smith’s long resume. It’s an oddity by anyone’s standards, and perhaps not the best pick to remember William Smith by, but because it’s so odd, it’s a natural for this blog.

The film begins with a scene that plays like the mother of all spooky campfire stories. A couple of quirky college students, Paul (Jay Scott) and Leslie (Kitty Vallacher) have parked their car out by the cemetery in the middle of the night (!?) to be alone so that Paul can propose. As Paul is putting a dime-store-looking ring on his girl’s finger, a prune-faced corpse (Michael Pataki) is waking up from his nap in a nearby crypt.

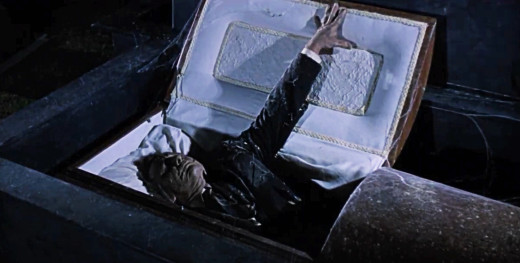

|

| "Next time I'm getting the satin interior." |

Before you can say “never make love next to a cemetery,” the rejuvenated corpse is tearing the door off the car to get to the couple. The living deadman hurls Paul onto a gravestone and proceeds to drain the unfortunate young man of his blood as his girlfriend, paralyzed with fear, looks on. The monster then turns his attention to Leslie, dragging her off to an open grave to do unspeakable things.

As a result of her night of trauma, Leslie is now pregnant, but being the eternal optimist, she is excited to be carrying Paul’s child. Her doctor is less sanguine, telling her that what’s inside her womb “isn’t human,” and urging her to terminate the pregnancy (interesting advice, given that the year is 1940, years before ultrasound imaging and legal abortions became available).

Meanwhile, the police detective working the murder-assault case (Ernesto Macias) is preternaturally open-minded and intuitive, somehow connecting the brutal draining of Paul’s blood with the case of a murderer-rapist in Boston, Caleb Croft, who was electrocuted trying to escape from the police. Sometime afterwards, Croft’s corpse was transferred to the very cemetery where the attack took place. Okaaaaayyyy.

When Leslie’s baby is born, he won’t take his mother’s milk. The midwife is worried, advising the young mother to see a doctor. Leslie refuses to go back to the man who wanted her to have an abortion. By chance, when Leslie accidentally cuts her finger and the baby greedily laps up the drops of blood that happen to fall near its mouth, she discovers just what he needs. She proceeds to draw her own blood to feed her child. Yikes!

|

| "I think you're going to like this. It's full-bodied, with notes of bitter cherry and tobacco, and a salty, piquant finish." |

Fast forward 30 years. Leslie’s child is now to all appearances a handsome, strapping young man, but one who knows he is… different. Calling himself James Eastman (William Smith), he has vowed to track down and destroy the monster who assaulted his mother.

His search has taken him to a college campus and the classroom of Prof. Lockwood (Pataki again), who teaches a class on folklore and mythology. In class, Eastman reveals his deep interest in vampires, particularly a 17th century English one by the name of Charles Croyden, who, after committing unspeakable depredations on his native soil, fled England for the Massachusetts Bay colony and assumed the name of Caleb Croft. Lockwood, who looks suspiciously like a less wrinkly version of the animated corpse who assaulted Leslie, listens to Eastman with apparent interest.

Eastman hooks up with two very attractive fellow students, Anne (Lyn Peters) and Anita (Diane Holden), who get swept up in the young man’s mission to find Caleb Croft and dispatch him to Hades. A series of grisly murders in the college town, in which the victims were drained of blood, seems to be proof he’s on the right track.

|

| James Eastman (William Smith) gets extra credit from Prof. Lockwood (Michael Pataki) for his extensive knowledge of vampire lore. |

Soon, one of the women will fall in love with Eastman and the other will implore Croft to make her his immortal vampire bride. And things will come to a bloody head when Lockwood/Croft invites his best students to earn extra credit by attending a seance at his mansion.

Like many low-budget horror movies, there are moments of inspired eeriness interspersed with scenes of jaw-dropping battiness.

The opening set-up of Croft awakening in his crypt is so classic as to be cliched, but is well done, especially the make-up, which is exactly how a vampire who hasn’t had a drop of blood in awhile should look.

For a newly awakened, desiccated member of the undead, Croft is amazingly strong and spry. The vampire ripping the car door off its hinges, breaking the young man’s back on a gravestone, and hauling the screaming Leslie off to the open grave is a shocking counterpoint to the languid, classic Dracula-like scene of Croft slowly opening the lid of the crypt.

But the film immediately follows up with its first head-scratching scene. Instead of being a skeptic, the investigating police Lt. immediately smells “Vampire!” Not only that, but he has somehow sussed out of thin air a connection to a certain Caleb Croft, a murderer and rapist who had been plying his nefarious trade in Boston.

Before we’ve had a chance to digest it all -- How does Panzer know so much about a murderer from out East? How did he make the vampire connection? Is he a secret vampire hunter as well as a policeman? -- the film cuts to the tender scenes of Leslie feeding her baby her own blood.

Similar head-scratching ensues with the scene of the first day of Lockwood’s class, when the 30 year-old Eastman regales the professor and the rest of the class with the legend of Croyden/Croft, the peripatetic vampire. What exactly, in his mission to hunt down Croft, has caused Eastwood to be in that town and that class? We don’t know. Eastman acts like he knows that Lockwood is Croft, or at least suspects it, but as things progress, he seems to be more interested in his attractive classmates, especially Anne, than in taking care of the monster.

|

| "I think you're going to like this, I was raised on this stuff!" |

There’s also the question of his status as a human/vampire hybrid. He can move around in the daylight and seems perfectly normal. Yet, as a baby, he could only thrive on blood. Is that still the case, or has he become more human as an adult? It seems like the latter, but the film doesn’t provide any definitive answers (at least not until the very end).

In the meantime, as Eastman dithers, Croft is draining local women of their blood. In Grave of the Vampire, women aren’t just unlucky, passive targets, but instead actively participate in their own victimization. Croft seems to exude a powerful animal magnetism. First, a young woman approaches him at night with a proposition to go back to her place. Then later, an attractive librarian lets her hair down in front of him after she’s closed up shop. And the hunky Eastman, seemingly a chip off the old block, has no problem attracting women either.

Croyden/Croft is a somewhat awkward mash-up of two more famous contemporaneous vampires. Like Janos from The Night Stalker (TV movie, 1972), Croft is extremely physical, capable of tearing apart cars and not above using whatever’s handy, including garden tools, to rip open victims’ throats before gulping down their blood. And yet, like Count Yorga (1970), he is refined and attractive, a ladies' man, luring his victims into his lair like a human spider.

Michael Pataki was an interesting choice for Croft. Pataki was one of those familiar TV faces that you could never quite place. Before Grave of the Vampire, he had appeared on such sci-fi favorites as The Twilight Zone, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and Star Trek (“The Trouble with Tribbles”), and he even had a small part in The Return of Count Yorga (1972). After Grave, he got a gig as Count Dracula in Dracula’s Dog (1977).

With a face and presence more suited to working class gangster roles than a centuries-old English vampire, Pataki still does a creditable job, especially in the wordless close-ups with blood dripping from his long vampire teeth. However, in the climactic seance scene, he goes over-the-top with a clipped, theatrical voice that sounds like a cheap stage magician trying to be heard in the back rows of a drafty theater.

|

| "What? Do I have something in my teeth?" |

Smith is a similarly odd choice as the vampire’s son. As the grown-up college student/vampire hunter, he is strangely passive and blank-faced, even when he’s being hit on by his beautiful classmates. It doesn’t help that the film doesn’t provide enough backstory to be able to make much sense of his motivations, or for that matter, where he is on the scale between human and vampire. It’s only at the end that he’s given a chance to get physical and decidedly emotional.

In addition to being thematically dark, Grave of the Vampire is photographically dark, with more than a few extended scenes of silhouettes moving against occasional patches of light. With Grave, it’s more of a feature than a bug. Like the film's juxtaposition of quiet, spooky scenes with bursts of extreme violence, the dark, can’t-quite-make-out-what’s-going-on sequences that stand cheek by jowl with the well-lit scenes of the mundane world (e.g., Lockwood’s classroom) keep the viewer off-kilter and not knowing what to expect.

Considering that Grave was shot in a little over a week for $50,000, it delivers a fair amount of frightful bang for its buck. And for William Smith fans, it’s worth seeing for a rare, quirky horror role that came almost smack dab in the middle of his crazy-long acting career.

Where to find it: With its public domain status, you can hurl a wooden stake in almost any direction and hit a copy. Start here or here.