George Pal’s timing was impeccable. His Operation Moon, later to become Destination Moon, was riding a wave of public interest in space, the culmination of nuclear anxieties coupled with V-2 rocket experiments and early space race cheerleading in the form of books like Willy Ley’s and Chesley Bonestell's Conquest of Space (1949). [1]

(Also not to be discounted is the first wave of public interest in flying saucers, precipitated by Kenneth Arnold’s famous 1947 sighting near Mt. Rainier in Washington state. The crest of the wave was a sensational article published in True magazine in January 1950, “Flying Saucers are Real.” Coming from a such an upright, authoritative source -- retired Marine Corps Major aviator Donald A. Keyhoe -- some readers might have been forgiven for thinking that space had already been claimed by the crafty Soviets or mysterious extraterrestrials.) [2]

Such anxious and heady times called for full blown efforts, not half measures. If we were going to conquer space, then we might as well conquer some territory as well. With mammoth multi-stage rockets already on the drawing boards, it seemed that our neighbor the moon, that destination of so many dreams over the centuries, was in reach.

Characteristic of the period was a lavishly illustrated Life magazine story, “Rocket to the Moon,” published in January 1949, while Pal’s Operation Moon was still in the planning stages. The article’s subtitle, “Man May Travel to Earth’s Satellite in 25 Years,” was prophetic, if somewhat conservative (it was just over 20 years later that the Eagle landed in the Sea of Tranquility). Space travel’s burgeoning roots in military technology and atom fever were touched on in the article: “Long a subject of fantasy, travel to the moon is now, as a result of recent scientific developments, not only a possibility but a probability. From tests made with the V-2 rocket engineers believe that a similar rocket, adapted to carrying humans, could make the 238,000 mile trip in about 48 hours.”

The article also addressed the challenges of achieving escape velocity with current chemical-fueled rockets. An illustration dramatically showed the performance gain of atomic power over more conventional fuel mixtures. (Probably not by chance, the Destination Moon rocket that would take off on theater screens the following year was atomic-powered.) Subsequent pages showed beautifully done pen and ink wash illustrations of a very plausible mission for its time.

|

| NASA diagram of the 'real world' moon rocket. |

Of course, it was a much more accurate prognosticator of the cinematic missions of 1950, with its moonship combining a command center, crew compartment and lander in one occupied by four astronauts. For both Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M, the Life illustrations could have been a storyboard -- particularly the moonwalk against a backdrop of craggy lunar mountains in the former case, and the sleek-looking spaceship with its bunk-style crew compartment in the latter.

With the dawn of a new decade, the synergy between popular magazines and movie productions, particularly Pal’s, became glaringly obvious. As Destination Moon was shooting, the canny producer invited a variety of scientific experts and writers to the set to witness movie history in the making. The resulting wave of articles celebrating the film months before it was released, was pure public relations gold. Articles in Life, Popular Mechanics, Popular Science and other publications rhapsodized over the production and its technical wizardry as if it were the final preparations for an actual moonflight.

Once the film was released, Pal exploited the coverage one more time in trailers: “The picture you’ve been reading about in every important national magazine and newspaper… among them, Life, This Week, The New York Times, Popular Science, Seein’ Stars, Popular Mechanics, Parade, The New York Daily News!” The trailer ends with the proclamation of Destination Moon as “The Miracle Picture of All-Time!” Indeed, a miracle for the time in its unprecedented special effects, and a miracle of promotion.

|

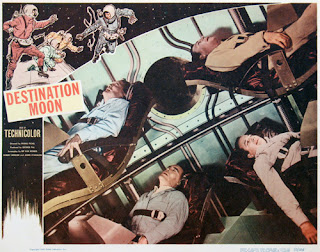

| Pal wanted Destination Moon to be as authentic as possible, right down to depicting the effects of G forces on lift off. |

Other production details included deflating couch cushions to make it appear the actors were sinking into their seats under the G forces of lift off, suspending spacewalking actors with body-length harnesses and wires, and making spacesuits appear to be airtight and pressurized with padding and wire stays.

In its coverage of Destination Moon around the same time period, Life’s writers seemed particularly intrigued by the use of “midgets” (sic) doubling as moon-walking astronauts in the background to provide the illusion of distance. One production still shows a little person actor being carried by a stagehand like a sack of potatoes over the set’s rough lunar terrain. The caption mentions moon-walking actors hoisted on wires to simulate leaps and bounds under the moon’s weaker gravity. (Interestingly, the Life article also picked up on the Cold War aspects of the film, opening with, “Believing that the nation that controls the moon will also control the world, four U.S. patriots prepare to take off in a 150-foot rocket ship based in the Mojave desert.”) [5]

|

| While it was already known by 1950 that there were no cracks in the lunar surface, they were added to lend perspective and make the set appear larger. |

And it concluded, “There isn’t much doubt that a trip to the moon and back will actually be made some day; enthusiasts are convinced that a missile will be landed on the moon in the next 10 or 15 years even if a manned space ship isn’t built for the trip by then. The chances are that when the space ship is built that it will be pretty much like the ship that the movie portrays. ‘Destination Moon’ will be released this fall, and George Pal jokingly says that he wants to make the release date as early as possible, otherwise the newsreels may beat him!” [6]

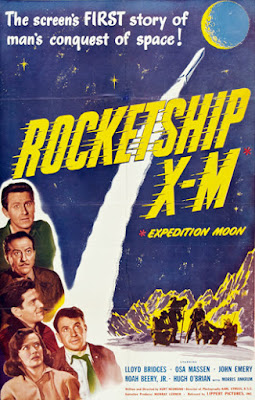

The newsreels didn’t beat Pal’s thunder, but, as mentioned earlier, a rival studio did. In competitive Hollywood, imitation has not only been the sincerest form of flattery, but a means for smaller studios and production companies to feed off the hot property scraps of their larger, wealthier brethren. In this Cold War-era side story, Lippert Pictures was a stand-in for the sneaky Soviets stealing nuclear secrets, and company head Robert Lippert did his best B movie imitation of a pugnacious Commie dictator jealous of the accomplishments of the Free World, and determined to one-up his rivals.

Rocketship X-M’s musical director Albert Glasser was a direct witness to the perfidy, as colorfully related to Tom Weaver:

“Lippert, the boss, called me in one day. Short, fat guy. He said, ‘Look Al, we’re going to do a big one, a science fiction thing called Rocketship X-M, and we’ve got to work very fast. The guy who wrote the script [writer-director Kurt Neumann] tried to peddle it all around town for a couple of years, no one wanted it. Why? It’s science fiction, who gives a shit about science fiction? But now, that big idiot, that asshole George Pal is making one about going to the moon. He’s been making it for a year and a half, and there’s trouble, trouble, trouble -- all of those special shots, the photographic tricks and whatnot. He even took out a five page ad in Life magazine, announcing that Destination Moon is on the way and will be out in about three or four months.’ So, Lippert said, ‘We’re going to knock Rocketship X-M out in three or four weeks. We’ll do it real cheap, and get ahead of him. George Pal is making everyone conscious about moon pictures. We’ll give ‘em moon pictures!’ So he did. We worked day and night, like sons of bitches.” [7]

|

| While Rocketship X-M had been set to land on the moon, it ended up on Mars instead! |

To add insult to injury, another Lippert tagline blared: “You've Read About It! You've Heard About It! Now SEE it!” While there was indeed some direct publicity of Rocketship X-M leading up to its premiere, Lippert was no doubt aware that the vast bulk of the pre-release publicity was focused on Pal’s bigger-budget effort, and if there was any confusion in moviegoers’ minds, then that was just fine.

In a sense though, there was never any real cinematic race to the moon. And not just because Lippert, concerned about potential legal action, decided to send his crew to Mars instead. Despite superficial similarities, the films were very different projects from the start. Pal, inspired by popular press speculations about spaceflight and its Cold War era implications, wanted to make those speculations as real and authentic as possible on the motion picture screen. To accomplish this, he hired the very visionaries, Robert Heinlein and Chesley Bonestell among them, who had done such yeoman work in the early post-war years, keying the nation into the importance of spaceflight. He went to great effort and expense to get it right.

Lippert, by contrast, was satisfied with simply establishing a veneer of space-age authenticity, the better to piggyback off of Destination Moon’s ubiquitous pre-release publicity. It was all about seizing the moment and making a pile of money by “giving ‘em moon pictures.” Yet, in spite of its hardscrabble, pecuniary origins, Lippert’s knockoff achieved another first, perhaps more important than being the first “hard” science fiction space flight movie in the new decade. It became the first cautionary film of the postwar Atomic era, depicting the world-shattering devastation of a nuclear war (on Mars no less!) at a time when Americans were being assured that such wars were winnable and just another option in the nation’s military arsenal.

|

| The crew of Rocketship X-M wonder how Google Maps steered them so completely off course... |

Each film is so different in its intent, tone and approach, and each is such an interesting artifact of its time, that the temptation is to declare them both winners in their respective categories: optimistic, “we can do it!” quasi-documentary in the case of Destination Moon, and exciting, yet sobering Atom-age cautionary tale in Rocketship X-M’s. Destination Moon in particular was a sizeable hit in its time, making over $5.5 million in box office receipts on its $586,000 investment. Together they helped propel the wave of sci-fi that washed over drive-ins and matinees and came to almost characterize the decade’s Hollywood product. And each has made its mark over the years with TV broadcasts and home video releases.

Notes:

- Willy Ley & Chesley Bonestell, The Conquest of Space: A Preview of the Greatest Adventure Awaiting Mankind, Viking, 1949

- Donald E. Keyhoe, "The Flying Saucers are Real," True magazine, January 1950, 11

- "Rocket to the Moon," Life magazine, January 17, 1949, 67

- Andrew R. Boone, "How Movies Take You on a Trip to the Moon," Popular Science, May 1950, 125

- "Destination Moon," Life magazine, April 25, 1950, 107

- Thomas E. Stimson, Jr., "Rocket to the Moon: No Longer a Fantastic Dream," Popular Mechanics, May, 1950, 89

- Tom Weaver, Science Fiction Stars and Horror Heroes: Interviews with Actors, Directors, Producers and Writers of the 1940s through 1960s, McFarland, 1991, 100

- Bill Warren, Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, Vol. 1, 1950-1957, McFarland, 1982, 11