Pros: Dark, noirish sci-fi thriller that cleverly breaks from the conventions of the day

Cons: Most of the special effects consist of footage borrowed from an earlier Russian film; The mix of American and Russian-shot footage is not seamless

This post is part of the John Saxon Blogathon hosted by the distinguished and prolific duo of Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews and Barry at Cinematic Catharsis. After you’ve paid your respects to the Queen of Blood, head on over to their blogs for more insights on John Saxon’s multi-faceted acting career.

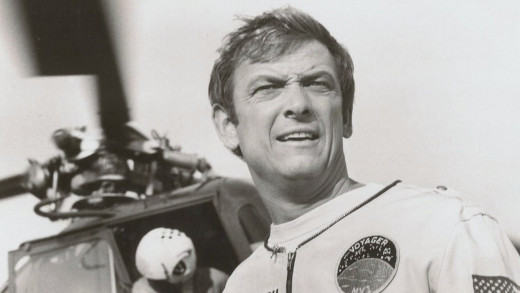

John Saxon was way too cool for school, and his dark, brooding good looks got him a break in Hollywood that would last for six decades.

Born Carmine Orrico in Brooklyn, NY in 1936, the newly minted actor John Saxon started out his movie career in the mid-’50s playing smoldering teen delinquents for Universal. The period was a high mark for juvenile delinquent movies, and Saxon was so good doing the teen angst thing in films like Running Wild (1955, with Mamie Van Doren), Rock, Pretty Baby (1956) and Summer Love (1958) that he began receiving fan mail by the truckload.

Saxon’s career took a detour when he secured a plum supporting role in John Huston’s Western The Unforgiven (1960; with Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn). For a short time it looked like he might spend the rest of his career riding horses, with The Plunderers (1960) and Posse from Hell (1961) following in quick succession.

While Saxon never became an A-list leading man, the versatile actor avoided being typecast or limited to any particular genre. And in his long career, he had the privilege of appearing in some truly remarkable and influential films.

Not content to hang around Hollywood, like a number of other contemporary actors he traveled to Europe to make films (the fact that he was fluent in Italian and had some proficiency in Spanish helped a lot. Wikipedia.). In Italy, he made The Evil Eye (aka The Girl Who Knew Too Much, 1963) with Mario Bava, which most regard as the first Giallo film.

A decade later, Saxon put his karate and judo expertise to good use, appearing with Bruce Lee and Jim Kelly in the mother of all martial arts films, Enter the Dragon (1973). A short while later he appeared in yet another seminal genre film, playing a police detective in Bob Clark’s pioneering slasher Black Christmas (1974).

|

| Saxon's likeness didn't always make it onto the posters, but he appeared in quite a few fun and influential genre films. |

Fast forward another decade, and Saxon played yet another detective in the first of the phenomenally successful A Nightmare on Elm Street movies. The horror genre, always lurking around the corner during Saxon’s long career, gave him his one and only opportunity at directing, when he took over the reins of Death House (1988) after the original director withdrew. (While the reviews for Death House are not good, Saxon is on record as saying the producers and he differed in their vision for the film, and the producers won. IMDb.)

Saxon’s sci-fi credits are not as numerous, but there are some interesting projects here and there. The actor’s first stab at sci-fi came while he was overseas. In the UK production The Night Caller (aka Blood Beast from Outer Space, 1965) Saxon plays a scientist battling aliens bent on kidnapping earth females for breeding purposes (where have we heard that one before?). Despite the ambitious premise, the low-budget film is very set-bound, with limited special effects.

More interesting is the TV movie Planet Earth (1974) that he made for Gene Roddenberry. The movie was Roddenberry’s second attempt to sell a series about a Buck Rodgers-like protagonist, Dylan Hunt, who wakes up from suspended animation into a very different, post apocalyptic world (Alex Cord played the hero in the first pilot, Genesis II, broadcast the year before). Alas, Planet Earth became yet another in a string of failed pilots for Roddenberry in the ‘70s.

With almost 200 acting credits spanning six decades, chances were good that a genre character actor like Saxon would find himself working for the most prolific of all B-movie producers, Roger Corman. And indeed, the actor appeared in several Corman productions, including what many regard as the best of all the Star Wars imitators, Battle Beyond the Stars (1980).

|

| The Queen is pleased by what she's seen after sitting through a John Saxon movie marathon. |

Star Wars upped the ante considerably for cinematic sci-fi, so Roger felt compelled to spend more than ever before -- around $2 million -- loading up his epic space opera with such stars as George Peppard, Robert Vaughn, Richard Thomas, Sybil Danning, and of course Saxon. And contributing to special effects that were a distinct upgrade for a Corman production (and that would be reused in multiple later films), was none other than a young James Cameron! [IMDb]

But back in the Queen of Blood’s day, the mid-60s, it was still possible to make sci-fi on the cheap -- and there was no one better than Roger Corman for squeezing a nickel until it begged for mercy.

Reading Queen of Blood's plot synopsis, with all its sci-fi bells and whistles, you’d think, after having seen one bloated, effects-laden epic after another steamroll their way through the 20-teens and twenties, that you couldn’t possibly pull off something like that for less than millions (even accounting for 1960s dollars).

Indeed, it’s nothing if not ambitious. The film is set in 1990, a year that, from the perspective of the ‘60s space race, was far off but not too far off, with more than enough time to ensure the conquering of the moon and the nearer planets. (Ah, the vagaries of fickle public support for piloted space exploration, and the meager NASA budgets that followed… but I digress.)

In Queen of Blood’s 1990, humanity has established moon bases, and Mars and Venus are next on the agenda to be colonized. The Astro Communications division of the International Institute of Space Technology has received messages from a mysterious, advanced civilization beyond the solar system that they will be sending an ambassador to Earth.

|

| Apparently, Queen of Blood's space program can also afford colossal statues. |

The Institute’s senior scientist, Dr. Farraday (Basil Rathbone) assembles all the staff, including astronauts Allan Brenner (Saxon), Laura James (Judi Meredith), Paul Grant (Dennis Hopper) and Tony Barrata (Don Eitner) to reveal the momentous news.

But, as in all things involving B-movie space travel, the best laid plans always go awry. The institute picks up an alien probe that landed in the ocean (what, the so-called advanced aliens couldn’t aim better than that?), and after viewing footage from the aliens’ flight log, determine that the ambassador’s spacecraft has crash-landed on Mars.

Things get frenetic and complicated as Farraday and staff set up shop on their moon base, and a rescue ship, the Oceana, with Laura, Paul and Commander Brockman (Robert Boon) on board, is dispatched for the Red planet. (Wait, no handsome and intrepid Allan Brenner on the pioneering flight? Don’t worry, read on…)

|

| To while away the time between missions, Allan and Dr. Farraday decide to start their very own podcast. |

The Oceana's instruments are damaged by an abrupt solar flare, but the astronauts manage to land near their target, where they find the crashed alien ship, but discover only one human-looking body and no ambassador. With the Oceana questionable and the ambassador still missing, Allan and Tony propose piloting a second ship to Mars with search satellites to help in hunt for the missing alien dignitary.

A-OK, except, as Farraday points out, the second ship doesn’t have the fuel capacity to get them to Mars and back. Thinking quickly, the brash space jockeys propose landing the second ship on the tiny Martian moon Phobos, and from there take a shuttle craft down to the Martian surface, where they’ll hook up with their colleagues and return on the Oceana.

As luck would have it, when Allan and Tony arrive on Phobos, they find yet another crashed ship -- the aliens’ emergency shuttle craft, complete with a very much alive alien dignitary (played by Florence Marly) -- conveniently near where they’ve set down. But then luck turns on them when they realize there’s only room for two on their own shuttle that will take them down to the Oceana, which is their ticket home. And, to add salt to the wound, the Oceana doesn’t have the fuel to pick up any lingering astronauts on Phobos and still make it home.

|

| The daring space jockeys come to the alien Queen's rescue. |

Tony gallantly insists that Allan accompany the ambassador (the consequence being that Tony will be marooned on Phobos until a relief ship can be dispatched to rescue him... sure, sure they will.).

Little do the astronauts know that, while the trips to Mars and Phobos were tense and hazardous, the trip back to Earth with their alien guest will be a doozy! At first the crew bend over backwards to keep their guest comfortable. It helps that, while her skin is a subtle shade of green, the alien is quite easy on the eyes in an exotic, outerspacey kind of way. She seems to have an aversion to earth women, glaring at Laura, but she takes quite nicely to dashing Paul, who acts like a smitten schoolboy as he helpfully shows her how to drink through a straw.

|

| "It's called a Big Gulp, your highness, and everyone on Earth is addicted to them." |

Commander Brockman takes his scientific curiosity a bit too far when he tries to draw the alien’s blood and she forcefully demurs. Brockman idiotically ventures to guess that she has a low threshold for pain (the consent thing seems to not have occurred to him).

But no worries, the Queen will soon turn the tables and draw blood from the earthmen -- she’s got a thirst, but not for scientific knowledge!

To say the least, that is a lot to cram into a 78 minute sci-fi B movie destined for the drive-in circuit. But this was child’s play for executive producer Roger Corman, who was extremely adept at making meager resources go where no resources had gone before.

|

| Laura and Allan discuss how they're going to break it to the Queen that they already gave at the office blood drive. |

One tactic was to offer directing gigs to talented new and aspiring filmmakers who would jump at the opportunity and be willing to work cheaply. Corman hired Curtis Harrington to write and direct. At this point, Harrington had only one other feature film under his belt -- the dark and moody (and critically well-received) Night Tide (1961, starring Dennis Hopper). But the art house-adjacent Night Tide hadn’t opened many doors in Hollywood, so Harrington was happy for the opportunity even if he didn’t have complete artistic control.

Another tactic was to let skilled artists and technicians on other films do your effects work for you. Harrington, in his memoir Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood, relates,

“The film would make use of some spectacular special effects footage from a Russian film to which [Corman] had acquired the American rights. Corman owned many of these films, and it seemed to have been a wise investment. I was to devise my own story that would incorporate scenes of a space station on the moon (from the Russian footage) with scenes of an alien spaceship stranded on one of the moons of Mars (which we would shoot).

The Soviet film, Mechte Navstrechu [1963], was a fable about the world’s natural fears of the nature of aliens, and the discovery at the end of the film was that the ruler of the aliens simply wants to be friends with us. I turned my film, Queen of Blood, into the exact opposite of this. I devised a tale in which the queen of the aliens …is a vampiric creature who seeks a new food source for her dying planet. The food source, as it turns out, is the human race.” [Curtis Harrington, Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood: The Adventures of an Aesthete in the Movie Business, Drag City Incorporated, 2013, p. 109]

(Alright, be honest, which movie would you rather see -- one about overcoming xenophobia and prejudice to unite with our spiritual brothers and sisters from another galaxy, or one about an evil alien monster in disguise stalking trusting, innocent humans and drinking their blood? I thought so.)

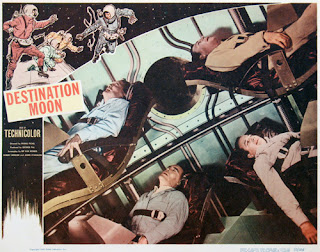

If there were just one or two scenes with the inserted footage, it would be one thing, But Queen of Blood relies extensively on the Soviet film for any sort of long, establishing shots, spaceships taking off, exteriors of moon bases, and weird, alien landscapes. The Mechte Navstrechu footage is dark, soft-focused and beautifully surreal, with reds and greens predominating, making the transition to the brightly lit American-shot interiors jarring.

|

| I don't suppose the Soviet filmmakers ever imagined that their beautiful work would be sold as fodder for an American capitalist exploitation flick. |

But as the tone of the film changes from one of triumph at rescuing the alien VIP, to suspicion and then disgust and horror at the monster in the astronauts' midst, Harrington’s scenes get progressively darker, with the ship’s interiors taking on a blood-red hue. Harrington also adds a subtle buzzing to the soundtrack as the alien stealthily moves around the ship, emphasizing that despite her appearance, she has more in common with a queen bee than a human being.

Not only does Harrington upend the tropes of Soviet Socialist filmmaking, he also slyly subverts those of his fellow American B moviemakers. In so many B sci-fi movies leading up to Queen of Blood, scientists were often first responders who discovered and tried to understand the threat, but it was the military that had to step in and take care of it. The granddaddy of such films was The Thing from Another World (1951), in which the tough military guys in bomber jackets shove aside the effete scientists who just want to communicate with the alien visitor, and roast the Thing like a big, humanoid marshmallow.

In Harrington’s contrary film, it’s the nerds in lab coats who win the day, overruling -- you guessed it -- our man of the hour, John Saxon, who, as the very straight-laced, all-American Allan Brenner, is repelled by the enigmatic Queen from the get-go (and very nearly loses his life to her).

|

| Allan reacts in disgust at the sight of the blood-gorged alien Queen... or is it his meager paycheck? |

SPOILERS: In spite of all the death and destruction the Queen has caused, the surviving astronauts (with the exception of Allan) are like automatons programmed to execute The Plan: defend and preserve the visitor at all costs for the benefit of scientific knowledge. When the ship returns to port, the scientists swarm around like kids in a candy store, collecting the eggs that the Queen has laid all over the ship (Ugh!). It’s a dark, cynical break with past tropes, and a harbinger of sci-fi to come.

As Harrington puts it in his memoir: “Some years later, it was very flattering to realize that I had created the prototype for a whole series of science-fiction movies dealing with monstrous creatures from outer space, beginning with Ridley Scott’s Alien.” [Harrington, p. 109]

|

| A Space Institute scientist serves up a tray of the Queen's special holiday deviled eggs. (Played by Forry Ackerman, founder of every Monster Kid's favorite mag, Famous Monsters of Filmland.) |