Now Playing: The Man Who Wouldn't Die (TV movie; 1995)

Pros: Roger Moore and Nancy Allen are good as unlikely partners trying to stop a madman; Provides enough satisfying twists and turns

Cons: Flirts with campiness; Malcolm McDowell hams it up a little too much as the villain

This post is part of the “You Knew My Name: The Bond Not Bond Blogathon” hosted by bloggers extraordinaire Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews and Gabriela at Pale Writer. Participants were asked to pick one of the six actors who have played James Bond and write about a non-Bond film he starred in.

When I was a kid, James Bond was a big deal. Back in the original Sean Connery days, Bond was one of those rare pop culture phenomena that both kids and adults could get excited about. I remember being sorely disappointed that I couldn’t go with Mom and Dad to see Goldfinger and had to stay at home with a babysitter. (Editor’s note: this was in the ‘60s, when parents were quaintly concerned about impressionable young minds being exposed to adult subjects, and leaving your kids with a babysitter was not tantamount to child abuse.)

However, just a year later the dam of parental concern was pretty much broken, and I was allowed to see Thunderball at a matinee. In just the first couple of minutes, I was wide-eyed watching Bond sock a woman in the jaw (actually a man in disguise) and escape via a jet pack. My lifelong fascination with “Bond, James Bond” was sealed.

While my parents smoked and drank martinis and talked about the latest Bond movies at cocktail parties (editor’s note: everybody over the age of 21 smoked and drank back then), my friends and I collected James Bond trading cards and action figures. I even had a Thunderball action figure set and a Corgi diecast Aston Martin with a working ejector seat just like in Goldfinger.

|

| The coolest toy ever! |

Being a starry-eyed Connery-Bond fan at the age of 10, it was a bit disconcerting to see Connery appearing in other movies, and not as James Bond. To my semi-formed mind, there was something not right about this. One of my friends saw Connery in The Hill, released the same year as Thunderball, which was a very serious adult drama about the mistreatment of British soldiers in a British-run military prison during WWII.

I didn’t get a chance to see it then (my parents had some limits after all), but I was amused watching my buddy recreating scenes from the film on the school playground, pretending to be Connery as an abused prisoner forced to do quick high step marching until he collapsed. Still, this just wasn’t right -- James Bond didn’t take abuse, he dished it out (but only to the highly deserving of course).

(By the way, I did eventually see The Hill, and I recommend it unreservedly. It’s a brutally realistic depiction of a very esoteric war subject. There are no false notes in the film, and the acting all around is superb.)

The Connery side ventures notwithstanding, the high point of the Connery-Bond years for me was when You Only Live Twice came to town in 1967. Humungous lines stretched around the block outside the theater. I didn’t experience anything else like it until years later, when the original Stars Wars debuted.

By the time Roger Moore stepped into 007’s shoes with Live and Let Die in 1973, I was a tad more mature and open minded about this new Bond who looked nothing like Sean Connery and had his own slyly humorous take on the character.

I was primed for Roger Moore as Bond because back in the ‘60s I had enjoyed a fair number of episodes of The Saint TV series, starring Moore as Simon Templar. The series, which ran from 1962 - 1969, was good practice for Moore in taking on the iconic Bond role. Templar is a sort of prototype James Bond, an international playboy and man of action who has a license to lie, cheat and steal for the greater good, so to speak.

But Roger had more to do in preparing to become 007 than just carrying over Simon Templar’s trademark arched eyebrow. In his memoir, Moore relates that the excitement of being tapped to succeed Connery wore off pretty quickly:

“I’d be the first to admit that I’d been living the good life in the previous year or so, while making The Persuaders [TV series with Tony Curtis] and being a movie mogul with Brut Films. That was brought home to me rather curtly when Harry [Saltzman, producer] called me one day.

‘Cubby [producer Albert R. Broccoli] thinks you need to lose a little weight.’

Okay, I thought. So I started a strict diet.

The phone rang again. ‘Cubby thinks you’re a little out of shape.’

So I started a fitness regime.

Again the phone rang, this time it was Cubby. ‘Harry thinks your hair’s too long.’

‘Why didn’t you just cast a thin, fit, bald fellow in the first place and avoid putting me through this hell?’ I replied.” [Roger Moore and Gareth Owen, My Word is My Bond, Collins, 2008, p. 173]

While some die-hard Connery fans were slow to warm up to the the especially dry humor Moore brought to the franchise, Moore continued 007’s winning ways on screen and at the box office, finally bowing out at the age of 58 (the oldest Bond to this day) with A View to a Kill in 1985.

|

| "Okay, okay, I'll go on your stupid diet -- now back off!" |

During Moore’s Bond run there were high points (Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me) and low points (Moonraker, A View to a Kill), but after Roger turned in his license to kill, I was never able to muster up the same level of anticipation for a new Bond film.

But at least I was mature enough by then to appreciate James Bond actors in other roles. In the midst of his Bond career, Moore doubled down on the action-adventure genre by portraying military men and mercenaries in such pictures as The Wild Geese (1978), Escape to Athena (1979), North Sea Hijack (1980) and The Sea Wolves (1980). It’s as if James Bond, as he entered his 50s, decided to loan himself out to mercenary operations to keep sharp in between spy assignments.

After A View to a Kill, Moore went into semi-retirement, not appearing in any feature films or TV shows until 1990. By that point he was in his 60s, and through with being an action hero. He still did a handful of action movies, but only in a supporting capacity.

With The Man Who Wouldn’t Die, an ABC TV movie of the week that originally aired in May, 1995, Moore traded in action thrills for mystery thrills, and his character is far less cocky than the spies, playboys and mercenaries of his acting heyday.

Moore plays Thomas Grace, author of a bestselling series of mystery novels featuring Detective Inspector Fulbright. His last novel, The Man Who Wouldn’t Die, pits Fulbright against master criminal Ian Morrisey, a character based on a real criminal, Bernard Drake (Malcolm McDowell). Drake was a genius sociopath who had killed a guard in trying to steal a legendary sword belonging to the royal family, and had been caught and sentenced to a maximum security prison.

In some exposition, we learn that Drake was supposedly killed in a fire at the prison, but in the midst of a sensational kidnapping and ransoming (and eventual murder) of an English Lord, Drake called Grace, taking responsibility for the crime and accusing the author of stealing from his life to create the character of Morissey.

Grace couldn’t get anyone to believe that Drake was still alive and up to his old tricks. Frustrated by police ineptitude, and alarmed by the supposed dead man who continued to hound him, Grace started a new life in America as a gossip columnist for a major city newspaper.

But Grace’s peace of mind doesn’t last long. In the film’s opening, Grace tags along with a crime reporter colleague (Eric McCormack of Will & Grace fame) to the scene of a murder. The police want to question Grace because someone put a copy of his last Inspector Fulbright novel, The Man Who Wouldn’t Die, under the corpse’s body.

Within due course he’s approached by a fan, Jessie Gallardo (Nancy Allen), a student and waitress who also happens to be psychic. Jesse claims that when she read the novel, she was able to see into Grace’s future -- specifically a man who is in the process of systematically reenacting crimes in the book.

|

| Grace is shaken at first, but is soon stirred into action. |

Grace is grumpily skeptical at first, but Jessie gets so many details right, including a spot-on description of Drake, that Grace is forced to concede that she is the real deal and that they need to join forces to foil the sinister plot. There’s only one problem: in another one of her visions, Jessie sees Drake shooting and killing Grace. In the meantime, the police are becoming increasingly suspicious of the columnist even as he’s protesting that it’s all the work of a man who is officially dead.

Even though there are explosions, chases and a megalomaniacal archvillain, The Man Who Wouldn’t Die is far more Sherlock Holmes than James Bond (although through much of the first half Grace is rattled and unsure of his next move, unlike either iconic hero).

For a TV movie made in the ‘90s, The Man plays like a mystery-thriller from the ‘30s, with wisecracking newspaper reporters and plucky young heroines sleuthing around in the shadows, always getting to the bottom of mystery before the clueless police.

The vintage ‘30s feel is especially strong in the first half, with scenes set in the offices of Grace’s unnamed newspaper, and the Eric McCormack character taking on the duties of the cynical, wisecracking reporter. (Interestingly, when Jessie enters the picture, McCormack is shunted off to the background -- two’s company, three’s a crowd.)

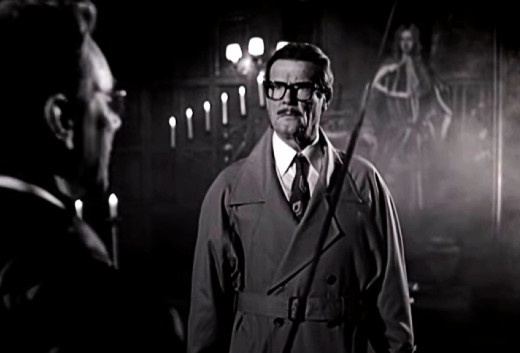

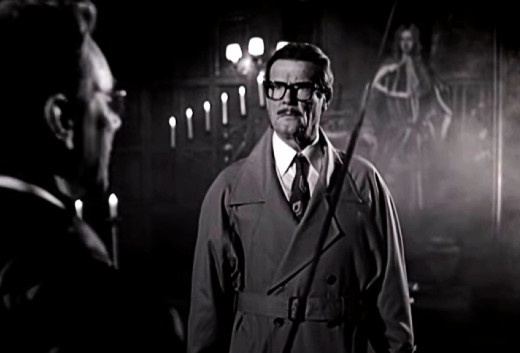

The old-timey atmosphere is further reinforced by intermittent black and white dream sequences of Moore and McDowell playing Inspector Fulbright and Ian Morrisey from Grace’s novel, reflecting the actions that are playing out for real as part of Drake’s revenge. These scenes are done in high camp style, but fortunately don’t get too much in the way of the real-world suspense.

|

| Roger and Malcolm as Grace and Drake playing Fulbright and Morrisey. Got that? |

The inclusion of the paranormal in the form of Jessie’s psychic visions is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it seems like a cheat: a device that in the beginning serves to alert Grace to the plot against him, and later, when the characters need to be put at risk for the sake of suspense, is conveniently turned off. At one point Jessie tells Grace that she can’t just conjure up her visions at will. Sure enough, that inability puts them, and the rest of the city, in danger.

On the other hand, Jessie’s second sight adds a needed element of uncanny wonder to the proceedings. The character would be far less interesting if she were just another generic young woman in peril drawn unwittingly into a sinister conspiracy. Her uncertainty about what some of the visions mean sets up the movie’s turnabout ending.

Nancy Allen was no stranger to thrillers when she made The Man Who Wouldn’t Die. One of her first film roles was in Brian De Palma’s 1976 adaptation of Stephen King’s Carrie. In the early ‘80s she appeared in two of De Palma's better-regarded thrillers, Dressed to Kill (1980) and Blowout (1981). Sci-fi fans will remember her for her portrayal of tough street cop Anne Lewis in the first three Robocop movies. In The Man Who Wouldn’t Die, her girl-next-door feistiness strikes just the right note in a role that someone else might have played too sexy or too enigmatic.

The Man Who Wouldn’t Die gave Roger Moore a chance to play a much gentler and more vulnerable sort of character (after all, aren’t most of us ready to settle down and stop cracking heads and blowing things up when we reach our 60s -- Liam Neeson and Sly Stallone excepted?). Roger’s less-is-more character starts off the movie anxious and indecisive, but Allen’s energy helps him regain his footing in time for the climactic battle with Drake.

As Drake/Morrisey, Malcolm McDowell serves up the ham in thick slices. Since his chilling portrayal of the glib sociopath Alex in A Clockwork Orange (1971), he has had ample opportunity to call on his inner arch-villain, most notably as Caligula in the infamous movie of the same name (1979), and as Soran in Star Trek: Generations (1994).

|

| "Who says my acting is over-the-top?" |

But he is far from a one-note actor. Perhaps his greatest role of all is as the gentle and resourceful H.G. Wells in Time After Time (1979), who pursues Jack the Ripper (David Warner) into the future and must use all his wits to prevent a young woman (Mary Steenburgen) from becoming Jack’s next victim.

Director Bill Condon has an interesting, eclectic resume. In the ‘90s he directed a string of made-for-TV thrillers, including The Man Who Wouldn’t Die. In 1998 he helmed the masterful and poignant story of director James Whale’s last days, Gods and Monsters, starring Ian McKellen and Brendon Fraser (he also wrote the screenplay based on the Christopher Bram novel). Since the turn of the century he’s been all over the place, directing the award-winning Dreamgirls (2006), two Twilight sagas, the live action Disney remake of Beauty and the Beast (2017), and most recently a cerebral thriller, The Good Liar (2019), with McKellen and Helen Mirren.

The Man Who Wouldn’t Die is a solid mystery-thriller that flirts with being camp, but is ultimately saved by a script with enough twists and turns to keep things interesting, and a good cast -- Moore and Allen especially -- who make their characters relatable and engaging.

Where to find it: Streaming