Pros: A prescient story of superpower miscalculations leading to global catastrophe; Believable, complex characters portrayed by a top-notch cast

Cons: A scene depicting young Londoners rioting over water restrictions is too tame to be believed

This post is part of the Second Disaster Blog-a-thon hosted by the always entertaining Dubsism and Pale Writer. After you’ve sweated it out here at Films From Beyond, head on over to their blogs for more cinematic disasters, catastrophes, fiascos and debacles than you can shake your head at.

Back in the late '50s and early ‘60s, there was no doubt about it -- if we were going to do ourselves in, it would be through nuclear war. The two hyper-powers that emerged from the ashes of WWII were testing the ultimate doomsday weapon, the H-bomb, that made the atomic bombs dropped on Japan look like firecrackers.

Anxious Americans were busy building backyard bomb shelters, practicing duck and cover drills and waiting for the sky to fall in. At the movies, they watched all kinds of rampaging creatures spawned by nuclear testing, or if they were in a particularly masochistic frame of mind, films like On the Beach (1959) or The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) that depicted small groups of survivors dealing with the aftermath of nuclear war.

Somehow, even with all the strategic tensions and the collective pessimism hanging around like a shroud, we managed to stumble through without blowing ourselves up (although the Cuban missile crisis was a terrifyingly close call).

Who would’ve thought that something as prosaic as belching billions of tons of fossil fuel emissions into the atmosphere would eventually take the place of the awesome and terrible H-bomb as the source of sleepless nights?

The Day the Earth Caught Fire is a film with a unique science fiction premise that presciently bridges the gap between nuclear and climate change nightmares.

Edward Judd stars as Peter Stenning, a newspaper reporter whose life has become a walking disaster area. Stenning recently went through a bitter divorce in which his ex-wife got custody of their 7-year-old son, and as a result he has taken to drinking.

|

| Stenning strolls down a deserted London street. In some of the film's original prints, the opening and closing scenes were tinted yellow to convey the extreme heat of a dying world. |

As a result, the once star reporter has been reduced to being a glorified gopher and writer of lifestyle puff pieces. Amid the usual newsroom hubbub over beauty pageants and pregnant royals, some unusual news items begin to draw the attention of the staff: sunspot-like interference with TV and radio signals; severe earth tremors in previously quiet zones; and unseasonably high temperatures and monsoon rains.

Stenning is assigned to contact the Met Office (the UK national Meteorological Office) to get background information on sunspots and climate data, but is initially blocked from speaking to the head honcho by a new employee in the office’s phone pool, Jeannie Craig (Janet Munro).

Later, when he visits the office in person on the pretext of picking up a press release, but with the intent of ambushing the Office chief to get a statement, he finds out Jeannie is a very attractive young woman who is not afraid to stick up for herself.

|

| Jeannie and Stenning take a relaxing bus ride through climate change-generated fog. |

Stenning and his colleagues at the Daily Express figure something is seriously amiss when a solar eclipse occurs 10 days before it’s due, and reports come streaming in from around the world on unprecedented flooding.

At an editorial meeting, a staffer brings up the recent tests of the most powerful H-bombs ever, one by the Russians in Siberia, the other by the Americans in Antarctica, that somehow, against all odds, had gone off almost simultaneously. Could the double bombs have anything to do with it? Nahhh….

Stenning tries to strike up a relationship with Jeannie -- he’s very attracted to her, and at the same time she’s a possible source of insider information. At one point he’s forced to camp out with her in her flat due to an unusually heavy fog (described as “heat mist”) that rolls into the city and causes everything to grind to a halt. Things start to heat up, literally and figuratively, for the two.

Soon, fog is the least of London’s worries. Unheard-of tornadoes blow half the city to kingdom come, then brutal heat and a withering drought dry up what’s left.

|

| London is treated to Mother Nature's Tilt-A-Whirl ride. |

The one good thing in a dust bowl of troubles -- Stenning’s and Jeannie’s budding romance -- is endangered when Jeannie confides to Stenning something she overheard at the ministry. Not only has the tilt of the earth been affected, but its orbit is now taking it dangerously close to the sun. In the heat of the moment (pun intended) Stenning promises Jeannie he won’t say anything, but his reporter’s instincts won’t allow him to be quiet.

The next day’s headlines blare “World Tips Over,” which also says it all for the couple’s relationship. Jeannie is taken into custody as a security risk, while the Daily Express staff grapple with the possible end of the world.

This being a serious treatment of a science fiction subject, Stenning does not come off as your typical sci-fi hero. He’s a complicated mess: at times cocky, at other times pathetically self-pitying, he tries to hide his insecurities behind a veneer of false bravado and cynical quips (example: “Why don’t I do 500 steaming words on how mankind is so full of wind it’s about to outblow nature?”).

His best friend at the paper (and seemingly only friend), veteran newshound Bill Maguire (Leo McKern), can only do so much for the self-destructive journalist. Maguire alternates between gentle chiding and ignoring him altogether when Stenning goes into his petulant teenager mode.

|

| "I'd like to cancel my steam bath appointment." |

Maguire is not only a sounding board and emotional backstop for Stenning, but serves as the conscience of the newspaper and a one-man Greek chorus. It’s Maguire who starts to piece things together as accounts of disparate disasters flood into the newsroom, and he is the one who adds the exclamation point to the hubristic folly that has sent humanity to the brink of extinction: “They’ve shifted the tilt of the earth. The stupid, crazy irresponsible bastards… they’ve finally done it!”

The Daily Express newsroom becomes a sanctuary/citadel for Stenning and Maguire as London turns into the equivalent of an overdone Shepherd's pie. Where once the paper was a busy hub for disseminating celebrity “news” and junk lifestyle pieces (“Thrombosis: How to be the death of the party”), as the crisis takes hold it becomes one of the last bastions of working civilization as the newspapermen grimly bang away on their typewriters. In one scene, Stenning, drenched in sweat and exhausted, sits down at his desk to compose one last story, only to find that the typewriter ribbon has melted.

But the show must go on, and the crusty old editor-in-chief "Jeff" Jefferson (Arthur Christiansen) continues to bark orders to his depleted staff: “Bill, get moving! I want a pictorial panorama of the world as it’s going to be with the new climatic zones and all the rest of it!” (Interesting side note: The Daily Express is a real newspaper that is still being published. Christiansen had been retired just a short time from his position as the paper's chief editor when he was talked into doing the role.)

|

| "And get me a list of all the places in London that are still selling ice lollies!" |

The newspaper is even a refuge for Jeannie, who has been released from custody (think of that -- she isn’t hauled off to a secret interrogation site, never to be heard from again!). The editor gives her a job in the newspaper’s library as a small recompense for Stenning’s broken promise. This gives Stenning the opportunity to try to make amends and win her back. Maguire urges him on, just wanting to see his friends happy in the little time that’s left.

There aren’t any heroes per se in The Day the Earth Caught Fire, just typical, flawed human beings who stubbornly and stoically cling to the last shreds of their normal lives as the world collapses around them. There is so much that rings true: government denials, then partial acknowledgements, then “let us pray” when the whole truth gets out. Adding to the misery are secret government plans to ration water, and outbreaks of disease as the depleted water supply gets contaminated. (One unintentionally comic scene is a water riot by juvenile delinquents that plays more like a fun day at the water park; look for Michael Caine in a bit role as a policeman.)

Fans used to disaster movies with epic CGI effects and droves of extras dying in spectacular fashion may be disappointed. There are effects -- the thick “heat mist,” cyclones, earthquakes, etc. -- that are crude by today’s standards, but effective enough for the time (see below). But in The Day the Earth Caught Fire, it’s the characters and their relationships that count. The ending is famously ambiguous, but there is more than a glimmer of hope in the depiction of average people who find deep reservoirs of courage in the face of calamity.

|

| The survivors from the Daily Express wait for the end of the world at the ultimate British sanctuary - the local pub. |

Where to find it: Streaming | DVD/Blu-ray

A Passion Project

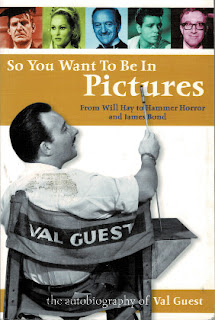

In an interview conducted years later, Val Guest, who produced, directed and co-wrote the screenplay, described how the film was a very personal project for him, one that took eight long years to secure funding:

“It was something that had been going around my head for a long time, that gradually we were f*cking up the whole planet. I had always been very interested in what we were liable to do to ourselves without realizing it. … [E]very time I made a movie and the [producers] said, ‘What do you want to do next?”, I’d tell them my idea and they’d say [disdainfully], ‘Oh, Christ! No one wants to know about the Bomb!’” [Tom Weaver, Attack of the Monster Movie Makers, McFarland, 1994, pp. 113-114]

He finally got British Lion films to cough up some money, but only on the condition that he put up one of his money-making films, Expresso Bongo (1960) as collateral. The film was made on a “ludicrously cheap” budget of $500,000.

The Fog of Filmmaking

For that money, Guest was somehow able to build an exact copy of the Daily Express office at Shepperton Studios “right down to the last piece of paper on the floor.” Only a few interior and exterior shots were required at the building itself.

Ironically, the weather was cold for much of the location shooting. At Battersea Park, the actors had to pretend that it was brutally hot:

“[W]ith everybody sunbathing, it was about fifty-eight, sixty degrees at most. And everybody was freezing -- in bikinis! We told them to keep their coats on until we were ready to shoot. That whole scene of Janet and Eddie Judd on the grass -- it was very cold weather. On the other stuff, Fleet Street and things like that, it wasn't at all cold, but the scene where it was supposed to be the hottest day of the century, it was a very cold day!” [Weaver, p. 119]

To add insult to irony, the day they shot the scene of the heavy fog enveloping London, the crew almost sparked a national incident:

“We had all these [fog] machines going, hundreds of extras -- the whole idea was that this strange mist was coming up the Thames and covering the whole of London. When we were very near the end of the shooting, we were suddenly invaded by about three or four police cars; the cops came up and said, ‘You must stop this immediately!’ What was happening was, just on the other side of the Thames was the Chelsea Flower Show, which the Queen was opening. And they had all this fog, pouring all over Her Majesty [laughs].” [Weaver, p. 119]

Validation from an unusual source

According to Guest, John F. Kennedy asked for a copy of the film and screened it for a gathering of foreign correspondents in Washington. In the interview, Guest didn’t mention (or perhaps wasn’t aware of) the context of the president’s interest: JFK came into office wanting to finish the work on a nuclear test ban treaty that Eisenhower started. The film may have helped in its small way, but it was the close call of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 that finally got the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed the following year.

The British film community also weighed in, awarding Guest and his co-writer Wolf Mankowitz the 1962 BAFTA award (the UK equivalent of the Oscars) for Best British Screenplay.

In his autobiography, Guest marveled at all the attention his “cheap” passion project received from various dignitaries after it came out. It makes a fitting postscript not only for him, but for the characters in the film:

“I mean, come on, for someone still in the throes of struggling to get it [the film] set up this would have all sounded like demented pipe dreams from the opium den. Which merely proves the worth of that sterling British Army advice in World War I: ‘Come what may, we press on regardless.’” [Val Guest, So You Want to be in Pictures, Reynolds & Hearn, 2001, p. 140.]