It’s blogathon time again! This post is part of the 9th annual Rule, Britannia Blogathon hosted by Terence Towles Canote at his A Shroud of Thoughts blog. After you’ve explored the dark world of Hammer film noir here, check out Terence's blog for more thoughts on films from the UK.

Mean streets. Dark alleyways. Conniving crooks. Corrupt cops. Double-dealin’ dames. To the classic film fan, it all seems as American as apple pie. Of course, greed, shady schemes and murder rear their ugly heads everywhere. And successful movie formulas have a tendency to spread far beyond national boundaries.

The term “film noir” originally circulated among French film critics in the late 1940s to describe Hollywood films of a certain dark, cynical type, but eventually grew to encompass a significant slice of world cinema that shared the same themes and style.

After the unprecedented horrors of WWII, the world’s popular culture could be forgiven for turning to the dark side, even in a country like the U.S. that emerged from the war stronger and more prosperous than ever.

Great Britain’s film industry had good reason to explore dark themes, as the war accelerated the decline of the empire and left Britons with shortages and rationing that lasted for years afterward.

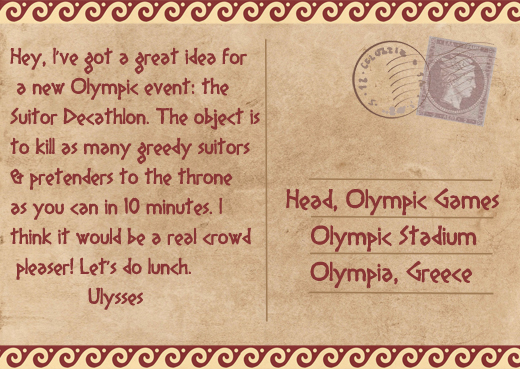

Years before Hammer Films became famous for its technicolor Gothic horrors, the studio cranked out low budget programmers in a variety of genres: mysteries, thrillers, comedies, a smattering of science fiction, and, especially in the post-war years, Hollywood-style crime dramas.

The director who was instrumental in helping Hammer usher in its horror renaissance, Terence Fisher, refined his craft on several gritty B crime pictures before unleashing The Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula on the world.

Many of these films were made by Hammer in arrangement with American distributor Robert L. Lippert, and featured at least one American star, backed by a solid British cast, to ensure box office appeal in the states. (The stars were either on their way up in the business, or more often, on the way down, and thus available to work cheaply.)

In many cases the titles were changed for American distribution -- it’s easy to imagine a frenetic, cigar-chomping Lippert dictating the snappy, hard-boiled titles to his gum-chewing, buxom secretary.

In addition to the two films discussed below, Fisher directed such noirish titles as Man Bait (1952), Dead on Course (1952), Man in Hiding (1953), The Black Glove (1954) and Kill Me Tomorrow (1957), among others. Other noir-sounding titles (directed by others) include: Bad Blonde (1953), Paid to Kill (1954), Heat Wave (1954) and The Glass Tomb (1955).

Beginning in 2006, VCI Entertainment, in association with Kit Parker Films, released DVD sets of what they called “Hammer Film Noir,” focusing on the Hammer-Lippert output of the early-mid ‘50s. While noir purists might take issue with the film noir designation for many of the titles, it’s nonetheless a great service to fans, highlighting an interesting period of Hammer film history that otherwise might swirl down the memory hole. Best of all, many of the sets are still available from online sellers.

Now Playing: Stolen Face (1952)

Pros: Presence of veterans Paul Henreid and Lizbeth Scott lends a veneer of A picture class

Cons: Character motivations and actions are contrived and unbelievable, as is the ending, which is also abrupt and unsatisfying

Despite the presence of once-superstars Paul Henreid and Lizabeth Scott that shouts FILM NOIR in all caps, Stolen Face is barely even a crime drama, instead shading into romantic melodrama territory, albeit with occasional glimpses into a somewhat tame British criminal underworld.

The film wastes no time in establishing its main character, Dr. Philip Ritter (Henreid), a renowned plastic surgeon, as someone too good to be true. In the opening scene, Ritter is playfully bantering with a young boy whose hand mobility he has saved, and reassures the mother who tells him she can’t pay him immediately. Then, after turning down £1000 to perform unneeded cosmetic surgery on a rich, vain dowager, he’s off to the local women’s prison to perform free plastic surgeries on deformed and disfigured inmates.

Ritter believes that correcting the women’s physical deformities can help them reintegrate into society. (A noble aspiration, but one wonders where the money for his practice is coming from, or if he’s just so rich that he doesn’t need it.) The warden has a new case for him -- Lily Conover (Mary Mackenzie) an habitual thief whose face was severely scarred in the London blitz.

Ritter interviews the coarse young woman and is intrigued. But on the drive back from the prison, the exhausted doctor nearly wrecks the car he’s driving, and is given marching orders by his associate to take a needed vacation.

Next thing he knows, Ritter is having a meet cute at an out of the way country inn with a glamorous American concert pianist, Alice Brent (Scott), who is similarly decompressing due to career stresses.

Ritter hears someone in the next room coughing and sneezing, and in reflexive doctor-mode he scribbles out a whimsical prescription for “two aspirin and a shot of whiskey,” which he slips under the door. The prospective patient turns out to be the beautiful and classy pianist. Fortunately, Alice has the aspirin and Ritter has the whiskey, (wink, wink, nudge, nudge).

|

| The doctor prescribes rest and relaxation in front of the fireplace. |

They both decide to stay on a couple of extra days, she supposedly to recover from her bad cold and he to take care of his new patient, but of course it’s all about the mutual attraction. They conduct a whirlwind romance via a montage sequence, saving some wear and tear on the viewer’s patience.

Just as Ritter is falling head over heels in love, Alice packs up and leaves with no notice. Later, back at his surgery, Alice calls, explaining that she is engaged to be married (to her manager, David, played by Andre Morrell).

Devastated, Ritter distracts himself with work, remembering his promise to Lily to make her into a new woman. In 1950s Britain, there’s no give and take between doctor and patient, especially for a patient who is a female convict. Lily is grateful for Ritter’s magnanimous attention, but she has no say in the ultimate outcome. She asks him twice what she will look like, and he tells her he doesn’t know. It’s just assumed she will look completely different, and presumably far more beautiful than she was prior to her injuries.

Ritter is set to go all-out Pygmalion on Lily. His surgical office looks more like an artist’s studio, with sketch pads lying about and a large clay bust representing the idealized Lily -- covered, so as not to spoil the surprise -- situated prominently in the center of the room. Lily’s face is just so much clay in the “artist’s” hands.

While outwardly solicitous and professional, inwardly Ritter is roiling with disappointment, so we know what’s coming. In yet another montage sequence, we see Alice playing the great concert halls of Europe, while Ritter uses his surgical skills to recreate his lost love. While I think montage sequences tend to be a bit tacky, in this case the intercutting between Alice and and the new “Alice”-in-the-making effectively serves to foreshadow the clash of doppelgangers at the climax.

As Lily/New Alice is recovering from her surgery, there is a shot, where Ritter is tenderly holding her bandaged arm, that reminded me of Colin Clive in the original Frankenstein hovering over the monster on the lab table like a proud new dad, or for that matter, the monster trying to take Elsa Lanchester’s hand in Bride of Frankenstein. Unfortunately from that point, instead of a horror-tinged noir, we get a rather staid British lesson in manners and class distinctions.

|

| An updated mad scientist's lab, circa 1952. |

Of course Ritter’s work is a complete success, and Lily emerges from the bandages an absolutely fabulous duplicate of Alice, at least physically. When Dr. Frankenstein’s Ritter’s associate learns of the doctor’s plans to marry his creation, all the do-gooder pretenses go out the window and upper crust revulsion at the lower classes takes over -- he protests that Lily is a recidivist criminal and psychopath (so much for salvaging the the not-so-good, the bad and the ugly through plastic surgery).

If this had been an American noir, there would have been a body count and hell to pay for the sheer hubris for trying to make a vulnerable, not-too-bright prisoner into the spitting image of a lost love. But instead, Stolen Face fritters away its potential with scene after scene of Ritter the dyspeptic elitist disapproving of his new wife’s lifestyle choices.

Lily’s/new Alice’s worst misdeeds in this ostensible crime drama are preferring jazz clubs to the opera, shoplifting a gaudy brooch and fur coat that her wealthy husband won’t buy for her (he uses his influence to make the charges go away), drinking too much and having raucous parties at their mansion.

The worst crime of all is that the film seems to side with the arrogant and selfish doctor, making him out to be the victim, and figuratively tsk-tsking at Lily’s antics like some blue-haired grand dame complaining about the help.

The court of stiff-upper-lip opinion brings the Hammer down on Lily at the climax. When Alice's fiancé David realizes who she is really in love with, he does the civilized thing and releases her from the engagement. Alice, unaware of the existence of Lily and the marriage, rushes to Ritter. Let’s just say there is hell to pay, and I’ll leave it to you to guess who pays it.

Despite the lost opportunities and the sour ending (your results may differ), the film is saved by the presence of ‘40s icons Lizabeth Scott and Paul Henreid (kind of like good plastic surgery that smooths over sagging spots and wrinkles).

Both were on the downslopes of their careers: Scott was still under contract to Paramount at this point and kept getting loaned out to indifferent film projects by a studio that didn’t know what to do with her; Henreid had been blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee as a “communist sympathizer” and was in no position to be choosy.

Scott is as beautiful and glamorous as ever in her dual role, believable as someone who could drive an esteemed physician batty with love/lust. Henreid, with his usual urbane sophistication and calm, assured manner, almost makes you believe that surgically altering a poor, hapless stranger and marrying her is a reasonable thing to do.

|

| It suddenly dawns on Lily that she's wearing someone else's face. |

Although crime dramas were numerous for Terence Fisher leading up to Hammer’s horror renaissance, they weren’t the only pictures he worked on. Just a year after Stolen Face, Fisher both wrote the screenplay for and directed Four Sided Triangle (1953), a low-budget, oddball sci-fi picture with an eerily similar premise.

Young, slightly mad scientists Bill and Robin (Stephen Murray and John Van Eyssen) have invented a matter duplicator. Both are in love with their childhood sweetheart Lena, who is back in England from an extended stay in the U.S. (Lena is played by blonde bombshell Barbara Payton, who -- yep, you guessed it -- was on the downside of her career due to scandals arising from her off-camera love life, including a fraught love triangle.)

When Robin successfully woos Lena and marries her, Bill decides to use the invention to make a duplicate of Lena for himself. Except that he didn’t figure that Lena 2 would be an exact replica in every detail, including her love choices.

In his book on Terence Fisher, film critic Peter Hutchings found at least one common thread in the director’s work from the early - mid ‘50s:

“As in the case with those other pre-1956 Fisher films that are distinctive in some way or other, there appears to be a conservative tone to the proceedings here. A comment made by the old doctor in Four Sided Triangle might well stand for this aspect of the work generally: ‘There is often less danger in the things we fear than in the things we desire.’ Desire is threatening, sexuality is dangerous, and anyone ‘infected’ with desire -- whether it be Bill in Four Sided Triangle, Ritter in Stolen Face, Duncan Reid in Portrait from Life or Chris in The Astonished Heart -- will suffer because of it. Yet at the same time this fearful emotion of desire is also an object of considerable fascination for the films. One outcome of this is that both Stolen Face and Four Sided Triangle reveal and dwell upon some of the more disturbing aspects of male desire, and their conservative but also somewhat contrived conclusions do little to resolve issues raised elsewhere in the films.” [Peter Hutchings, Terence Fisher, Manchester University Press, 2001, p. 67]

|

| Lily rips off the bandages to reveal her new face... Oops, wrong movie! |

Bonus Review:

Now Playing: Blackout (1954)

Pros: Dane Clark’s energetic performance; Belinda Lee is the coolest of cucumbers

Cons: One too many plot twists make it hard to keep up without a scorecard

Unlike Stolen Face, Blackout is the real noir deal. It asserts its credentials in the opening scene, where a down and out American, Casey Morrow (Dane Clark), is getting stinking drunk at a London jazz club, with only an ashtray full of cigarette butts to keep him company.

Enter a luminously beautiful and classy mystery woman (Belinda Lee) who, before Morrow passes out, offers the broke American £500 to marry her that night! In the morning, he wakes up with a huge hangover in a strange artist’s studio/apartment, with no memory of the night's events, and bizarrely, sitting in the middle of the room, a portrait on an easel of the very same mystery woman.

The artist/apartment tenant, Maggie Doone (Eleanor Summerfield), tells Morrow that he showed up in the middle of night banging on her door. Neither Maggie or Morrow know how he got there.

Things start to get interesting when Morrow finds out from the morning newspaper that the mystery woman is wealthy heiress Phyllis Brunner, her father has been murdered, and Phyllis is missing.

When Morrow goes to pay the newspaper vendor, he discovers a wad of pound notes in his pocket. It wasn’t a dream after all, and now he’s a person of interest in the murder. Morrow is going to have to become his own private investigator if he’s to clear his name, and there are a lot of possible guilty parties: was it Phyllis herself in a bid to inherit the family fortune and pin the murder on Morrow; or the sketchy solicitor Lance Gordon (Andrew Osborn), Phyllis’ supposed fiancé and the family business manager; or even Mrs. Brunner (Betty Ann Davies), who may have suspected that her husband was stepping out on her?

|

| If a beautiful blonde who is way out of your league takes a sudden interest in you, watch out! |

Blackout is another in a long line of noirs featuring protagonists suffering from memory lapses or amnesia who have stumbled into a world of trouble, and must race against time to clear their names -- Two O’Clock Courage (1945), Fear in the Night (1946), High Wall (1947), The Crooked Way (1949) and Man in the Dark (1953) are just a handful of examples.

The film checks off a bunch of noir elements, including apparent double-crosses, real double-crosses, red-herrings, corrupt wealthy families and their equally corrupt lawyers, psychopathic henchmen, and best of all, the patented icy blonde femme fatale who can turn on the charm when she needs something from a man.

Leading man Dane Clark owns the film from beginning to end. Clark is a man apart in a world of pursed-lip Britishness, rattling off screenwriter Richard Landau’s hard-boiled dialog and borderline non-sequiturs like a Brooklyn-accented dervish:

Morrow: “The last time Miss Opportunity knocked at my door, I let her in.”

Phyllis: “Oh, what happened?”

Morrow: “Now I haven’t even got a door.”

And,

“Because when he turns up, if he turns up, he’s going to be the deadest man ever killed!”

After some work on Broadway, Clark jumped into movies in the early ‘40s. His first credited role was in the war picture Action in the Atlantic (1943) with Humphrey Bogart. He spent the war years playing average Joe, All-American soldiers, sailors and airmen in such pictures as Destination Tokyo (1943), God is My Co-Pilot (1945), and Pride of the Marines (1945).

By the late ‘40s he was “decommissioned” as a Hollywood soldier and joined the ranks of noir protagonists, appearing in Whiplash (1948), Backfire (1950), and two other Hammer near-noirs, The Gambler and the Lady (1952) and Paid to Kill (1954).

Clark is one of the Hammer-Lippert partnership’s better leading men, and his spirited, wryly humorous performance is ample reason to check out Blackout.

|

| "Where have I seen that face before?" |