Pros: Manages an uncanny atmosphere, especially in scenes in which Vorelli (the ventriloquist) and Hugo (the dummy) argue as they perform their stage act.

Cons: Skimpy production values; Yvonne Romain is somewhat wasted in a role where she is in a hypnotic trance or semi-conscious for much of the movie

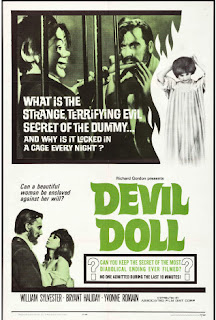

This post about a man and his devilish dummy is part of The Mismatched Couples Blogathon hosted by the prolific and ever reliable bloggers Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews and Barry at Cinematic Catharsis.

According to Psych Times, pupaphobia, or fear of puppets, is a real anxiety that can be debilitating for adults as well as children. While most of us don’t break out in a cold sweat at the sight of a ventriloquist’s dummy or a marionette (or heaven forbid, a muppet), it’s not for the entertainment industry’s lack of trying. Marionettes are one thing, but ventriloquist’s dummies, with their larger size and moving heads, mouths and eyes, can evoke a sense of the uncanny in even the most rational adult.

In 1945, the mother (or should I say father?) of all creepy dummies, Hugo, appeared in the pioneering UK anthology horror film Dead of Night. Years later, Hugo inspired not one but two sentient dummy episodes on The Twilight Zone: “The Dummy” (S3, Ep. 3, 1962), featuring a ventriloquist (Cliff Robertson) whose dummy is the real brains of the act, and “Caesar and Me,” (S5, Ep. 22, 1964), which tells the tale of an alcoholic ventriloquist (Jackie Cooper) whose wooden sidekick convinces him to pull off a series of robberies. (Interestingly, the same dummy prop was used in both episodes.)

|

| I hope this dummy was smart enough to collect overtime from Mr. Serling. |

Even before The Twilight Zone became a home for delinquent dummies, Alfred Hitchcock Presents got in on the act with the episode “And So Died Riabouchinska,” (S1, Ep. 20, 1956). Based on a Ray Bradbury short story , Riabouchinska flips the dummy script with an uncanny and beautiful female mannequin who cannot tell a lie -- and becomes a witness in a murder investigation involving her ventriloquist (Claude Rains).

And then there’s Magic (1976), about a sort of love triangle involving a man, his dummy, and the ravishing Ann-Margaret. (Magic’s box office didn’t do anyone associated with it any favors, but it has since acquired a minor cult reputation.)

Perhaps as much as any of the above listed movies or TV episodes, Devil Doll will put your pupaphobia to the test (or maybe jump start a bad case if you don’t already have it). The titular “doll” Hugo, like his Dead of Night namesake, is unsettlingly ugly in the classic evil dummy way. This particular Hugo ups the creepiness factor in his ability to walk around on his own with no strings or hands attached (courtesy of 4’ 1” Sadie Corrie, who wore a Hugo costume for those scenes).

His “master,” The Great Vorelli (Bryant Haliday), is no less off-putting, but in an intense, Svengali-like way. Together they make an exceedingly creepy mismatched couple.

But they’re not the only odd pair in Devil Doll; the film is positively brimming with regrettable or unlikely relationships among abusers, abusees and those about to be abused. Let’s count:

1. Vorelli and Hugo. Vorelli, who has been selling out shows in the London theater district, has a dual act: hypnotizing volunteers on stage, and then closing with the dummy Hugo, who departs from the usual ventriloquist routine by getting up, walking up to the footlights, and addressing the audience on his own.

Vorelli has a sadistic streak. In an early scene, he hypnotizes a volunteer and convinces the poor blubbering man that he’s about to be executed. The ventriloquist part of his act is all about taunting Hugo that he’s just a dumb block of wood, while Vorelli can eat and drink wine and live life to the fullest. Hugo (or is it really Vorelli?) protests that he can drink wine too, and is thirsty. It’s a sad, depressing routine, but then, Hugo shuffling around the stage is a genuine showstopper. (Later, there’s an additional hint that Vorelli isn’t in complete control of his dummy when we see that he locks Hugo in a cage when he’s not performing.)

|

| Vorelli pours himself a glass of wine while Hugo wishes he had an esophagus. |

2. Mark English and Marianne Horn. Mark (William Sylvester) is an American expat working as a reporter for a London tabloid. His editor wants him to get the scoop on the new sensation in town, The Great Vorelli. He enlists his girlfriend, the beautiful and wealthy Marianne (Yvonne Romain) to volunteer to be hypnotized at Vorelli’s next show in the hopes of exposing him as a charlatan.

Mark and Marianne are a mismatched couple -- he’s rough around the edges and pushy, and she’s somewhat passive and unsure of herself. At the theater Marianne gets cold feet about volunteering, but Mark, thinking about nothing but his story, goads her into it. Big mistake. Considering her elite status and how beautiful she is, she could do a lot better.

|

| "C'mon, don't be such a baby -- what's the worst that can happen?" |

3. Vorelli and Marianne. Vorelli couldn’t have hoped for a better subject to fall into his hypnotic clutches. Using his sinister powers, he wrangles an invitation to a charity ball being hosted by Marianne’s wealthy aunt. At the ball, Vorelli solidifies his hypnotic power over Marianne, and she falls into a feverish semi-coma. When she comes out of it, she robotically professes her love for the hypnotist and tells Mark she plans to marry Vorelli.

Maybe this couple isn’t as mismatched as it seems -- he likes money and she’s got a lot of it. Except that once they’re married, her life won’t be worth a plugged nickel.

|

| Don't look him in the eyes... |

4. Vorelli and Magda the buxom stage assistant. Poor Magda (Sandra Dorne) has hopelessly fallen for her boss, but his attentions are lasered in on the beautiful Marianne. In desperation, she threatens to turn him into the police if he doesn’t make an honest woman of her. Vorelli deals with the situation by telling Hugo that Magda is dishing dirt on him. Exit Magda.

But perhaps the biggest mismatch of all is the combination of hypnosis and ventriloquism in Vorelli’s act (I guess they don’t call him the Great Vorelli for nothing). Sure, hypnosis and ventriloquism have been mainstays of vaudeville for years, but it seems like combining the two could quickly go south -- like a tired Vorelli mixing up the routines and trying to stick his hand in a **ahem** inappropriate place on his volunteer’s person.

|

| Vorelli has another great talent: tuning out things he doesn't want to hear. |

Producer Richard Gordon, whose credits include such B gems as The Haunted Strangler (1958) and Corridors of Blood (1958; both starring Boris Karloff), and cult sci-fi favorites like Fiend Without a Face (1958) and First Man Into Space (1959), was proud to have pioneered this odd mash-up:

“One of the interesting things about Devil Doll is that it’s the first time that hypnotism and ventriloquism were brought together and incorporated into one film. Hypnotism in the movies goes back to the days of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari [1919]; and in 1926, Boris Karloff played a Caligari-like hypnotist in a picture called The Bells, in which he uses hypnosis to unmask Lionel Barrymore as a murderer. And Barrymore himself used hypnotism to solve the killings in Mark of the Vampire [1935]. But I don’t think it had ever been used in conjunction with ventriloquism before.” [Tom Weaver, The Horror Hits of Richard Gordon: A Book-Length Interview, BearManor Media, 2011, p. 111.]

Devil Doll’s script, by Ronald Kinnoch and Charles Vetter, was based on a story by Frederick E. Smith that had appeared in an English pulp magazine.

The film definitely lives up to (or down to, according to your taste) its pulp roots. There are a lot of close-ups of Vorelli mesmerizing his victims, and of Hugo’s pug-ugly face with only a slight movement of the eyes betraying that he’s anything other than a wooden prop. (Especially pulpy is a scene in which Vorelli, trying to mollify Magda, beds her, and we get a peek at the voluptuous assistant in her birthday suit.)

|

| Seriously now, DON'T LOOK HIM IN THE EYES! |

The frequent close-ups lend the film a sort of claustrophobic feeling, as if we the viewers are being hypnotized and can only see and obey Vorelli. Relying on close-ups also allowed Gordon to get the film in the can for something between $60 - $70 K, less than even the previous Karloff films or the sci-fi Bs:

“In making any low-budget movie, one tended to use closeups more frequently and more prominently than otherwise, because it helped to reduce production costs; you didn’t have to light and dress up a whole set in order to shoot a scene.” [Weaver, p. 112]

Of course, the real star of the show is Hugo, who is both animated and ambulatory. Dummies who could move on their own had been done before, but they tended to work in the shadows when no one was looking.

On the other hand, Devil Doll Hugo’s uncanny ability to walk is part of Vorelli’s stage act, so something else is going on beyond hallucinations or a disturbed ventriloquist investing his dummy with the other half of his split personality.

|

| The Dummy walks! |

When, after the charity ball, Hugo visits Mark in the middle of night and cryptically implores him to “Help me. Find me in Berlin… 1948…” Mark takes the hint and travels to the German capital to look into Vorelli’s and Hugo’s past. Apparently Vorelli was no mere classically trained hypnotist or vaudevillian, but was also a dedicated student of Eastern occult arts. And it’s that occult knowledge, combined with hypnosis, that has Mark worried about Vorelli’s designs on Marianne.

Speaking of interesting pasts, Bryant Haliday had as much of an intriguing, if less sinister, career arc as the character he played. Initially interested in theology, he spent some time in a monastery, then took a detour to study international law at Harvard University.

At Harvard Haliday caught the acting bug, and guaranteed himself a wealth of experience by helping to establish the Brattle Theater company and the Cambridge Drama Festival. Then, branching out into films, he and a Harvard colleague co-founded Janus Films, the first American distributor of such international cinema luminaries as Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Michelangelo Antonioni. (Haliday has been featured on the blog before -- see my review of another Richard Gordon / Bryant Haliday collaboration, The Projected Man.)

|

| Bryant Haliday gives his pitch to a potential Janus Films investor. |

Also no stranger to the blog is Yvonne Romain (Marianne), who was last seen here providing the love interest for Oliver Reed in Hammer’s swashbuckler Night Creatures (aka Captain Clegg, 1962). Romain's horror credits include a small role in Gordon's Corridors of Blood (1958), Circus of Horrors (1960; in which her disfigured face is restored by a scheming plastic surgeon played by Anton Diffring), and Curse of the Werewolf (1961; where she once again hooks up with the cursed Oliver Reed).

American William Sylvester’s notable genre appearances include Gorgo (1961; playing a sailor who helps his Captain capture a juvenile prehistoric monster), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968; playing a NASA administrator trying to deal with the discovery of a mysterious monolith on the moon).

While Devil Doll is not the perfect cinematic ventriloquist’s act -- the emphasis on close-ups makes it seem more like a TV show than a movie, and it squanders Yvonne Romain by keeping her hypnotized and/or semi-conscious for much of the running time -- it does manage a few genuinely creepy moments.

Shots of Hugo staring (but maybe not quite blankly) out from between the bars of his cage, and close-ups of his small, stiff legs as he shuffles down a hallway in the dead of night, are enough to elicit an uncanny shudder or two. There is a Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode featuring Devil Doll out there, but I would take in this ventriloquist act without the hijinks.

|

| Hugo bides his time in solitary confinement |