Now Playing: Prototype (TV movie, 1983)

Pros: Intelligent, poignant script; Great, nuanced performances, especially by leads Christopher Plummer and David Morse

Cons: Certain plot elements, such as the authorities’ measured, non-violent response to a rogue scientist running off with a top-secret military project, may seem quaint in these anxious times

This post is part of the Charismatic Christopher Plummer Blogathon hosted by Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews and Gabriela at Pale Writer. In a brilliant career spanning over 6 decades, Plummer played a dizzying array of characters in almost every movie genre, from Captain von Trapp in The Sound of Music (1965), to Sherlock Holmes in Murder by Decree (1979), to billionaire oil tycoon J. Paul Getty in All the Money in the World (2017). Prototype is a nearly forgotten TV movie, but it’s a great example of how this extraordinary actor could make any role something special.

In 1920, Czech playwright Karel Capek introduced the word robot to the world in his play R.U.R. (aka Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti or Rossum's Universal Robots). Even before that, filmmakers were fascinated with the idea of artificial humanoids. In 1918, Der Herr der Welt treated German audiences to the idea of “machine people” performing society’s hard labor; in the United States, the great Harry Houdini faced off against a criminal cartel employing an “automaton” in the serial The Master Mystery (also 1918).

It didn’t take long for clunky, box-like robots to evolve into androids indistinguishable from real people. In Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), a deranged inventor (Rotwang) fashions an exact duplicate of Utopian prophet Maria, which proceeds to wreak all kinds of havoc in its human guise.

While the traditional movie robot can be either intimidating or ludicrous depending upon its look, androids are uncanny and potentially insidious, calling into question what it means to be human … and possibly representing the next stage of evolution that threatens to leave frail, error-prone homo sapiens in the dust.

|

| Okay, so I doubt this specimen will be replacing humanity anytime soon... |

Blade Runner (1982), based on a novel by the visionary author Philip K. Dick, depicted a future (i.e., 2019) in which replicant androids are perceived to be such a threat that they’ve been banned from Earth. ”Blade runners” -- futuristic bounty hunters -- are employed to eliminate any replicants that have slipped through the net and are passing themselves off as human.

More recently, Ex Machina (2014) dealt with the near future of android research, in which a young computer programmer spends a week with a Zuckerberg-like tech mogul and his beautiful (and devious) android creation.

Prototype exists in a brighter, more hopeful world than the dystopian Los Angeles of Blade Runner or the tech-dominated surveillance state of Ex Machina. Nobel award-winning scientist Dr. Carl Forrester (Christopher Plummer) and his team have put the finishing touches on Michael (David Morse), the world’s first full-fledged, high functioning android. In his excitement at the success of the project, Forrester bends the lab rules and takes Michael out for a “field trip” to a department store and then dinner at the scientist's home. Forrester tells his wife Dorothy (Frances Sternhagen), a linguistics professor, that Michael is a work colleague.

Tall, lanky, polite to a fault and with an almost cherubic face, Michael is the very picture of a socially awkward, nerdy young scientist. The improvised Turing test goes off almost without a hitch, except for Michael’s inability to eat or drink -- Forrester’s solution is to distract his wife and pile Michael’s salad onto his own plate. Michael offhandedly comments that he should have been designed to ingest food.

|

| Dr. Forrester is worried that he will have to eat his dinner and Michael's. |

Back at the lab, Forrester brags to his colleague Dr. Pressman (James Sutorius) that on the field trip “it [Michael] handled a crisis and made associations!” The laboratory director, Dr. Arthur Jarrett (Stephen Elliot) is not nearly so sanguine about the test, chewing out his chief scientist for exposing the secret government project to such risk. Forrester, flush with success and the natural arrogance of an elite scientist, brushes off Jarrett’s protests.

Forrester’s brashness turns to alarm when a military detachment pays a visit to the lab and whisks Michael off to Washington for further tests. When they return Michael to the lab, Forrester and his team examine him from head to toe, concerned about what the military may have done to their creation.

They discover gunpowder residue on Michael’s hand, and Forrester goes ballistic (no pun intended) on Jarrett and General Keating (Arthur Hill), the Pentagon’s liaison to the project. Keating, trying to calm the situation, admits that among many tests they had Michael fire a weapon, pointing out that the project team has given them something “with a thousand uses.”

Unmollified, Forrester fears the worst -- that the Pentagon is planning to use Michael as an assassin or super-soldier. Exasperated, Keating hints that even project heads can have their security clearances revoked.

|

| Forrester and his team are highly suspicious of the Pentagon's plans for Michael. |

When Forrester learns that Keating is planning to take Michael back to Washington, possibly indefinitely, he enlists the aid of Pressman to sneak Michael out of the lab one more time. The pair go on a road trip, ultimately ending up at the quiet little campus where Forrester got his start. But their hideout won’t last, as the military isn’t going to let a top secret project slip through their fingers for long.

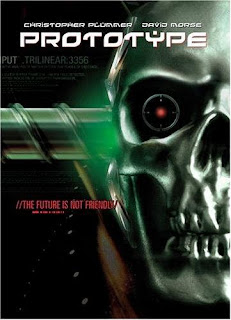

Sandwiched in between Blade Runner (1982) and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s The Terminator (1984), Prototype was first broadcast on CBS on December 7, 1983. In contrast to the two cult hits, Prototype doesn't bother with any shootings, explosions, car chases or any kind of physical violence. (But that didn’t prevent the marketing people from creating very Terminator-like art for Prototype’s home video release and adding the ominous tagline “The future is not friendly”.)

Instead, writers/producers Richard Levinson and William Link, who, among other things, gave the world Columbo and Murder, She Wrote, opted for a poignant drama that explores the varied ways human beings might react when faced with an artificial intelligence that looks like us, acts like us and can pass for us -- and how that intelligence might evolve and view us in turn.

The lead characters, Forrester and Michael, make journeys of self-discovery through the course of the movie. In the opening scene, the first stop on Michael’s field trip to the outside world is a busy department store during the Christmas season. Michael, over 6 ft. tall and dressed in a turtle-neck sweater and slacks, is a wide-eyed man-child captivated by a model train display. Forrester lurks in the background like a bemused parent -- a foreshadowing of the relationship to come -- and has to urge Michael along, as they have a dinner date to keep at the good doctor’s house.

|

| Even 6' 4" tall androids can be fascinated by model trains. |

At first, Forrester is the gruff and demanding scientist, obsessed with putting Michael through his paces and proving that he is indistinguishable from the real thing. In the presence of colleagues Forrester refers to Michael as “it,” and barely notices when Michael expresses amazing, human-like longings, like wishing they would let him read books in the regular, linear way instead of downloading them directly into his artificial brain.

When they go on the run, the scientist becomes a stern parent. In one instance, Michael is watching a rerun of the 1931 Frankenstein in their hotel room. Forrester tells Michael to shut off the TV, snapping that he shouldn't be watching something that “trivializes science.” Michael innocently responds, “It was a sad story -- do they kill him? [the monster]” Forrester pretends not to notice the association that Michael is making.

Later, at their hideout at Forrester’s alma mater, Frankenstein comes up again. Like any rebellious teenager, Michael rejects his mentor's advice and reads Shelley’s novel. He confesses that he’s having “very strange thoughts” as a result. He tells Forrester that the book is nothing like the movie, and at the end the creature chooses to lose himself in the ice flows of the North Pole. He sadly concludes that Frankenstein’s monster was luckier -- he followed his own nature. “I’m not anything, I’m whatever anyone wants me to be.”

Ironically, Michael’s growing self-awareness breaks down Forrester’s own automaton-like rigidness. Living in close quarters with Michael and witnessing so many aspects of his humanness opens up the dour scientist’s eyes. Forrester evolves from the stereotypical scientist only interested in numbers and benchmarks, to a worried, proscriptive parent, to a man humbled and in awe of the gentle, sensitive being he has brought to life.

|

| Father and artificial son go fishing. |

Forrester realizes that Michael is not just a blank slate for himself and others to write upon and nurture, but also the author of his own life. Plummer is pitch perfect throughout his character’s transition. Forrester’s best moments come when, toward the end of the film, with the government tightening the net around them, he gleams with fatherly pride even knowing that their relationship is hanging by a thread.

David Morse also gives an outstanding performance as Michael. There is no makeup involved in making Michael look just a tiny bit off. It’s all on Morse, who gets it just right: he's a bit too wide-eyed, he doesn’t blink, his posture is a little too straight, his movements and speech a little too precise. But he’s not so off that he can’t pass for human. In other words, he’s the stereotypical socially awkward nerd.

Michael has a number of poignant moments as his personality blossoms from child-like enthusiasm for a toy train to growing independence as he takes an unauthorized trip to a campus bookstore and chats innocently with an attractive store clerk.

Another thing that separates Prototype from the run-of-the-mill sci-fi movie is its treatment of the antagonists, lab director Jarrett and General Keating. These are not one-dimensional B movie villains.

Jarrett is a harried administrator, caught between his passionate star scientist and the Pentagon. He’s also a little sensitive about his status as a paper pusher who doesn’t do “real science,” but his heart is in the right place, and he doesn’t want to see Forrester blow up his career.

One of the film’s most heartbreaking scenes comes after Forrester and Michael have fled, and Jarrett is talking with Dorothy. As delicately as possible, Jarrett suggests to her that, since the couple never had a child, Michael may have become a surrogate son for her husband. Dorothy ruefully concedes that “at this moment, he must love Michael more.”

|

Dorothy is suddenly surrounded by government officials concerned for her welfare...

and wanting to know where her husband is. |

Similarly, Arthur Hill as General Keating is not your standard cigar-chomping, bullying military man, but rather an urbane, articulate technocrat who seems genuinely honored to meet Forrester. He wants to reassure the scientist, but is honest enough to admit he doesn’t know what the Pentagon will ultimately do with Michael.

In fact, the authorities in Prototype are so reasonable (and the lab’s security so lax, with Forrester managing to sneak Michael out not once but twice), a contemporary viewer could be forgiven for thinking the whole thing takes place on another planet. Prototype is a far cry from our current 24/7 surveillance world, where authorities are more disposed to locking up whistleblowers and protesters for long prison stretches than humoring them.

At this point in his career, Plummer was taking work where he could get it, staying busy with TV series and TV movies, the occasional feature film, and even lending his distinctive voice to animated family movies. Sci-fi was in the mix here and there -- several years before Prototype, he appeared as The Emperor of the Galaxy in the ultra-cheesy, low-budget Star Wars rip-off Starcrash, co-starring Caroline Munroe and David Hasselhoff. In 1984, he co-starred as a villainous government official opposite Dennis Quaid and Max von Sydow in the underrated sci-fi thriller Dreamscape.

Prototype was one of David Morse’s first screen credits, but by the time it went into production, he was already making a name for himself as Dr. Jack Morrison in the TV series St. Elsewhere, which lasted six seasons. Since then, Morse, like Plummer, has appeared in a wide variety of roles on TV and in feature films, and, despite his boyish, All-American looks, has proved to be as adept at playing creepy villains (e.g., 12 Monkeys, Disturbia) as stand-up good guys.

|

| Michael develops a sudden interest in reading and girls, in that order. |

With this modest, character-driven TV production, Levinson and Link took the opportunity to play with themes and ideas that are definitely not the stuff of blockbuster movie hits. They wisely avoided loading down Prototype with too many lengthy philosophical exchanges, instead letting the great cast reveal their characters just as much or more through looks, gestures and offhand comments. The result is one deeply affecting moment after another.

If you see Prototype and it doesn’t bring even the tiniest hint of a tear to your eye, you should get over to your local AI-Robotics lab for testing. You might just be an android with a defective emotion chip.

Where to find it: Streaming