Last year I wrote about how, in spite of societal pressures to restrict women to roles as wives, mothers and homemakers, quite a few sci-fi movies of the ‘50s bucked the prevailing norms and featured strong, intelligent women scientists and doctors who were right there with the men battling all kinds of monstrous menaces. I purposely excluded women astronauts, as this was yet another robust category of sci-fi roles that went against the grain, and I wanted to give them their due in a post of their own.

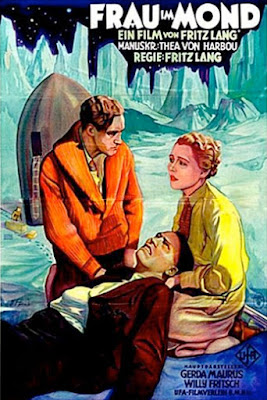

Cinematic depictions of female pioneering astronauts got a very early start with

Fritz Lang’s science fiction epic

Woman in the Moon (aka

Frau im Mond), which premiered in Berlin in October, 1929. Written by Lang’s then-wife

Thea von Harbou, the silent movie tells the story of the first expedition to the moon.

A wealthy industrialist, Wolf Helius (

Willy Fritsch), becomes interested in Prof. Georg Manfeldt’s (

Klaus Pohl) theory that the moon is abundant with gold, and starts planning for a trip to the moon to test the theory. The ship takes off with a crew consisting of Helius, Manfeldt, Walter Turner (representing a rival group of businessmen, played by

Fritz Rasp), and Helius’s two assistants, Hans Windegger (

Gustav von Wangenheim) and Friede Velten (

Gerda Maurus). After launch, they discover a stowaway in the form of a young boy, Gustav (

Gustl Gstettenbaur), whom Helius had befriended earlier.

Lang took great pains to make his moon trip as realistic as possible according to the scientific knowledge of the day. The director brought in rocket expert

Hermann Oberth to advise, and the result accurately predicted what many aspects of future space flight would look like. At a time when American

Robert Goddard was experimenting with rickety-looking liquid-fueled rockets that could barely travel more than a mile high,

Woman in the Moon depicted a multi-stage rocket launching from a pad, and the crew experiencing G-forces and zero gravity. The film is also famous for using the first launch countdown -- added for dramatic tension and adopted decades later by NASA.

The hard science fiction elements serve as a launch pad for more conventional human drama featuring a love triangle between the industrialist and his two assistants, espionage, blackmail, and betrayal. It’s not only remarkable that Friede is part of the crew of the first moon mission (and that the rocketship is named for her), but that she also takes heroic and poignant action to ensure the ship’s safe return to earth.

|

| Okay, so Woman in the Moon didn't get everything right... |

Such a passion for enlisting scientific expertise to ensure the most realistic cinematic spaceship ride imaginable wouldn’t be seen again for decades, until George Pal’s

Destination Moon blasted off in theaters in 1950. Based on a

Robert Heinlein novel (and co-scripted by the author), Pal’s film had libertarian, anti-government undercurrents amidst all the techno-razzledazzle. And it was definitely a “boys only” affair -- unsurprisingly, no women were selected for that mission. In contrast, the other quasi-realistic space picture that actually beat

Destination Moon into theaters that year, Robert Lippert’s

Rocketship X-M, featured a brilliant female scientist, Dr. Van Horn (Osa Massen), as part of the crew. To add further fuel to the competition,

Rocketship X-M also set itself apart from Pal’s picture with a grim anti-nukes message (see my two part series on the race between Pal and Lippert to be the first to put a movie spaceship on the moon,

here and

here).

If the sausage-fest

Destination Moon had been the only popular moontrip audiences saw that year, subsequent movie space flights might also have been largely male-only affairs. But

Rocketship X-M captured a good share of the popular imagination, and Osa Massen’s dynamic, pioneering presence undoubtedly influenced a number of B moviemakers to add women to their spaceship crews.

Just like my previous post on women scientists in ‘50s sci-fi films, I’ve included a very select list of women astronauts -- please use the comments to add anyone that I’ve overlooked. Like last time, each entry lists the astronaut’s resume, her biggest screen moment, and, because the fifties weren’t exactly a high point of female empowerment, the biggest “cringe” moment of embarrassing sexism.

Resume: Dr. Van Horn is a distinguished chemist and assistant to moon mission commander and lead scientist Dr. Eckstrom (

John Emery). Her research into “monatomic hydrogen” has resulted in a fuel concentrated and powerful enough to enable interplanetary spaceflight.

Biggest screen moment: SPOILERS! After a disastrous encounter with the savage remnants of an ancient Martian civilization that leaves two crewmembers dead and the navigator (

Hugh O’Brian) injured and delirious, Van Horn and the pilot, Col. Floyd Graham (

Lloyd Bridges) manage to lift off from the Martian surface. Lisa does her best to navigate the ship back to earth, but there’s not enough fuel left for a landing. She and Graham get on the radio and inform HQ of everything that went wrong with the mission -- and their theory about the Martians blowing themselves up in a nuclear war -- so that the people of earth can avoid future tragic mistakes.

|

| Van Horn and Graham wax poetic under the light of the silvery moon. |

Biggest cringe moment: Early in the flight, the ship’s engines inexplicably power down. When the crew reports that they can’t find any equipment malfunctions, Eckstrom determines the problem must be with the fuel mixture. He and Van Horn get to work using pencil and paper (!!) to determine an optimal mixture to restart the engines. When their figures don’t agree, Van Horn adamantly insists that she hasn’t made any errors. In overruling her, Eckstrom becomes patronizing: “surely you’re not going to let emotion enter into this!” After she apologizes, he rubs salt in the wound: “[Apologize] for what? For momentarily being a woman? It’s completely understandable Miss Van Horn.” She refrains from saying “I told you so!” when the rocket accelerates exponentially and goes wildly off course, missing the moon entirely and hurtling toward Mars.

Additional notes: Massen, born in Denmark, was working as a news photographer and had plans to become a film editor when she was tapped for a role in a Danish crime film. She was quickly imported to Hollywood at a time when studios were recruiting waves of Scandanavian actresses in an attempt to find the next Greta Garbo. She worked mostly in B movies during the ‘40s, and television (of course!) starting in the early ‘50s. Her other sci-fi/horror credits include

Cry of the Werewolf (1944) and a guest spot on the

Science Fiction Theatre TV series (1955).

Resume: Carol’s father was a respected physicist, and she has followed in his footsteps, becoming first assistant to the chief engineer and co-designer of the Mars rocketship, Dr. Jim Barker (

Arthur Franz). Although she is a computational whiz with responsibilities for calculating navigational trajectories and fuel usage, she is also a whiz at pining hopelessly for Barker, who is more interested in spaceships than women.

Biggest screen moment: Unfortunately, Carol is a wash-out in the heroics department, as she spends almost the entire movie pouting over Jim. However, it’s a Martian woman who ends up saving the day. Alita (

Marguerite Chapman) is Carol’s counterpart in the underground Martian civilization that the expedition discovers. She is also the daughter of a famous scientist and a formidable one in her own right. Alita steps in to assist Jim in repairing the ship for its return to earth. Moreover, when she learns that the Martian ruler plans to take over the ship once repairs are done and use it to invade earth, she devises a plan for the earthlings to stall for time while they secretly get the ship ready to blast off.

|

| Carol is not happy that shoulder pads have made a comeback on Mars. |

Biggest cringe moment: Mid-way in their trip to Mars, the crew members are sitting around ruminating about the mission, the cosmos, life, and the meaning of it all. When the senior scientist, Prof. Jackson (

Richard Gaines) gloomily states that he expects the ship to be his coffin, the rest of the crew dumps on him for being so pessimistic. Carol passionately stands up for the professor: “He’s contributed more than any of us, a real wife, a home, two lovely grandchildren… I’d trade ten trips to Mars for that!”

Additional notes: Virginia Huston, like her character Carol, seems to have preferred marriage and family over career. She retired from acting in the mid-fifties after appearing in a baker’s dozen of movies and TV shows. Along the way, she appeared in the classic noirs

Out of the Past (1947),

Flamingo Road (1949) and

Sudden Fear (1952), and also was Jane to Lex Barker’s Tarzan in

Tarzan’s Peril (1951).

Marguerite Chapman kept busy during the 1940s making dozens of B movies. By the mid-fifties she was working almost exclusively in television, appearing in such classic anthology series as

Lux Video Theatre and

Studio 57. Her last film role was in Edgar G. Ulmer’s sci-fi cheapie

The Amazing Transparent Man (1960).

Resume: The film doesn’t waste any time on character backstories or preparations for the mission. Early on, we learn that Helen is the ship’s navigator on humanity’s very first mission to the moon. She’s apparently so good at her job, she can navigate a complex spaceship and attend to her looks at the same time (see her big cringe moment below).

Biggest screen moment: Alpha (

Carol Brewster), leader of the ancient civilization of lunar Cat-Women, informs Helen that they plan on taking over the spaceship with her help and pilot it back to earth -- without the male crew members. When Helen, who is being telepathically manipulated by Alpha, objects that she’s only the navigator and needs the men to help operate it, Alpha’s second in command snickers: “Show us their weaknesses and we’ll take care of the rest.” Helen, staring off into space, responds, “It’s strange, I should care what happens to them… and yet I don’t!”

|

| “Calling all stations…clear the air lanes…clear all air lanes for the big broadcast!”

|

Biggest cringe moment: At the outset, the film tries to generate suspense by showing the crew in their reclining seats suffering from the g-forces generated by the rocket’s take-off. When the ship reaches outer space and the crew start to move around the cabin, the first thing Helen does is to fish out a comb and hand mirror from a drawer and fiddle with her hair. When the mission commander (

Sonny Tufts) asks her if the ship is on course, she perfunctorily replies “On course,” without looking at her console and without missing a stroke.

Additional notes: “Queen of the B’s” Marie Windsor’s dark hair and smoldering eyes made her the perfect femme fatale for crime dramas and film noir. Among her better known noirs are

Force of Evil (1948, with John Garfield),

The Narrow Margin (1952), and Stanley Kubrick’s

The Killing (1956). Sci-fi/horror outings were rare, but after

Cat-Women she played the enigmatic Madame Rontru in

Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955).

Resume: Dr. Ryan is a brilliant biologist and zoologist, and the daughter of a renowned scientist (being related to a prominent male scientist seems almost to have been a prerequisite for women scientists of ‘50s B movies).

Biggest screen moment: SPOILERS! “Irish” heroically comes through in a pinch not once but twice. First, she saves the ship from a giant Martian amoeba that’s enveloped it by suggesting sending an electric current through it. Then, after she’s single-handedly piloted the ship back to earth, she comes up with a way to save the life of the pilot, Col. Thomas O’Bannion (

Gerald Mohr), who is near death after a portion of the amoeba has attached itself to his arm. Even though she is recovering from shock and exhaustion, she rallies, and remembers an old experiment she conducted with earthly amoebas, also involving electric current.

|

| O'Bannion helps Irish adjust the straps on her spacesuit. |

Biggest cringe moment: During some downtime on the way to Mars, O’Bannion tries out his lounge lizard lines on Iris:

O’Bannion: "You know Irish, you’re the first scientist I’ve ever known with lovely, long red hair."

Ryan: "And you’re the first pilot I’ve ever gone to Mars with. And listen, my name is Iris, not Irish! I never know if you’re calling me by name or nationality!"

O’Bannion: "When I call you by name, you’ll know it!"

A few minutes later, Iris dabs some perfume behind her ears when she thinks no one is looking.

Additional notes: After

Angry Red Planet, Nora Hayden’s career largely consisted of guest shots on TV series. She wrote and starred in her last film,

The Perils of P.K. (1986), about a former movie star working as a stripper in Las Vegas who has dreams of reviving her movie career. The film had an interesting and diverse cast including Dick Shawn, Sammy Davis, Jr., Larry Storch, Louise Lasser, and Joey Heatherton, among others.