Pros: Beautiful, haunting cinematography and production design; Enhancements to the original folk tale add to the drama and tension.

Cons: Some scenes depicting village life are repetitive and run a little too long.

I love a good ghost story. Back when I used to prowl around used bookstores (it seems like a lifetime ago), I was always on the lookout for classic collections and true paranormal accounts.

In contrast to the cathartic jolt of straight horror, the classic ghost story evokes a sense of disquiet, dread and the uncanny. The short hairs at the back of the neck stand up, shadows threaten to turn into apparitions, and routine nighttime creakings are suddenly alive with ominous possibilities.

Ghosts are really in their element in the winter, when the long, cold nights remind us of our mortality, and that only a thin veneer of civilization separates us from things that live in the shadows.

Even in the era of the electric light, ghost stories are traditionally told by a roaring fire, which for millennia has warded off the night and all its threats. It’s a comfortable way to take a short, safe journey to the unknown, all the while whistling past the graveyard and reassuring ourselves that we’re among the living in a bright, warm reality.

The traditional ghost story also has a built-in safety valve. Ghosts are incorporeal -- shades, shadows, remnants -- which are confined to specific locations. They can’t really hurt you, unless you let them get into your head.

Or so it is with Western tradition. The supernatural folklore of East Asia is a whole other matter. There are a dizzying variety of ghosts from all walks of (former) life pursuing all kinds of missions in the afterlife. And many are far more than mere place-bound revenants, with the ability to roam the countryside and torment the living with powers that would make a Western ghost transparent with envy.

|

| Yuki-onna (the snow woman) from the Hyakki-Zukan |

For the average Westerner, a ghost is a ghost (with the exception of the poltergeist, which is unseen but makes its presence known by throwing physical objects around like a spoiled child). In Japan alone, the spirits of the dead -- the Yūrei -- line up into categories as if they were filling out some census longform in purgatory.

Onryō are hell-bent on revenge for wrongs done to them in their lifetime; Goryō are vengeful too, but come from the upper classes (so much for the idea of the afterlife erasing class distinctions); Ubume are mothers who died in childbirth; Funayūrei are poor souls who died at sea; Zashiki-warashi are the ghosts of children, and the Fuyūrei are condemned to float aimlessly around in the air. There are place-bound Japanese ghosts -- Jibakurei -- but unlike Western tradition, they are rare.

As if that weren’t enough, there are the Yōkai, spirits (and sometimes monsters) that originate from nature and the earth itself, rather than representing the souls of the dead. They can take on almost any aspect, from human to animal to inanimate objects, and some can shapeshift if they get too bored. Like the Yūrei, they can range from benevolent to deadly malevolent and everything in between.

The spirit-protagonist of The Snow Woman (1968) belongs to this second category. All by herself, the Snow Woman seems to have as many folkloric variations as the Inuit people have names for snow. As Zack Davisson in his article “Yuki Onna - The Snow Woman” poetically describes her,

“The Yuki Onna is one of Japan’s most well-known and yet unknown yokai. There is no single story of the Yuki Onna. From dread snow vampire of the mountains to a loving bride and mother, she has played many roles over the centuries; worn many costumes. She is ephemeral as a windblown mist of snow, and as impossible to hold.” [Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai website, https://hyakumonogatari.com/2013/12/18/yuki-onna-the-snow-woman/ ; 12/18/2013]

The 1968 movie is an expanded version of the Snow Woman tale popularized by writer Lafcadio Hearn in his 1904 collection Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

Hearn, born in Greece to a Greek mother and Irish father, emigrated to the United States while still a teenager and soon took up work as a newspaper reporter. He eventually ended up in Japan, where he would spend the rest of his life under a new name, Koizumi Yakumo. He married a Japanese woman from a prominent family and had four children.

Davisson notes in his article that Hearn’s story, “Yuki-Onna,” became so well known and popular that it largely supplanted other variants of the Snow Woman in the Japanese public mind. Yuki-Onna makes a memorable appearance in “The Woman in the Snow,” one of four Hearn stories included in the award-winning Japanese film Kwaidan (1964).

SPOILERS AHEAD (but knowing how it ends shouldn't affect your enjoyment)

The story as told in Kwaidan is a simple one. Two wood cutters, an old man and his young assistant Minokichi, are forced to take shelter in a hut during a blinding snowstorm. Enter the Yuki-Onna, who kills the old man by freezing him with her icy breath. She is about to do the same to Minokichi, but instead takes pity on him as he is so young. She warns Minokichi that if he ever tells anyone of the encounter, even his mother, she will kill him.

|

| Kwaidan's spooky, icy realm of the Snow Woman. |

Some time later, as Minokichi is returning to the village after a hard day of work, he meets Yuki, a young woman without a family who is traveling to the capital in the hopes of finding work as a servant. Before you know it, the two are married with three beautiful children. The women of the village are in awe of Yuki, as she doesn’t seem to age, despite her lowly circumstances.

Minokichi is a very lucky man and knows it. One evening, he and Yuki are preparing clothes and new sandals for the family to wear at an upcoming festival. At a certain angle in the lantern light, Yuki reminds Minokichi of the Snow Woman, and he makes the mistake of telling his wife about the encounter. She reveals herself as the Yuki-Onna, accusing the cowering man of breaking his oath, but once again spares his life for the sake of the children. Yuki disappears out into the snowy night. Heartbroken, Minokichi places her sandals outside as a sort of offering; the snow covers them, and they too disappear.

Screenwriter Fuji Yahiro expands the 1968 Snow Woman tale by making the young man, Yosaku in this version, an apprentice to a master wood carver. When the pair encountered the Snow Woman, they had been out scouting for the perfect tree to use to carve a statue for the local shrine.

Sworn to secrecy upon pain of death, Yosaku (Akira Ishihama) tells his master’s wife that the wood carver died of exposure. Orphaned at an early age, Yosaku had been taken in by the couple and raised like a son, apprenticed in order to learn the intricate art of wood carving.

|

| The Snow Woman's stare will freeze you in your tracks. |

Yosaku spots the ethereally beautiful Yuki (Shiho Fujimura) seeking shelter nearby from a heavy rain, and invites her in. As in the original story, she is an orphan who is traveling to the big city to seek better opportunities. When the mistress of the house takes ill, Yuki demonstrates her extensive knowledge of the healing arts, and the old woman is soon back on her feet.

Yosaku and the mistress are both taken with Yuki, and persuade her to stay. Their idyllic life is soon broken by the cruel and arrogant Bailiff of the province, who brutally beats the mistress when she intervenes to protect some village children who have accidentally rolled logs into the path of the Bailiff’s horse.

As she is dying, the mistress makes Yuki promise to marry Yosaku. Five years later, Yosaku and Yuki are happily married with a healthy and playful young son. But the encounter in the woods with the Snow Woman still hangs over their heads like a Sword of Damocles.

Even though the master wood carver died, the “perfect” tree that the pair had found was cut down and transported to the village. The head priest of the local shrine decides that Yosaku has learned his craft well under his master, and chooses him to carve a very important goddess statue that will be a centerpiece for worship.

|

| Yuki and Yosaku enjoy a brief moment of peace and quiet. |

Rather than an honor, Yosaku’s appointment turns out to be a curse. The young man’s feelings of unworthiness are exacerbated by the heavy responsibility. Worse yet, Yosaku’s renown has attracted the attention of the Bailiff, who wants the beautiful Yuki all to himself.

The Bailiff hatches a plan to charge Yosaku with trespassing in the prefecture’s woods and stealing the tree, despite the master and apprentice having gotten permission. If the couple don’t come up with a fortune in gold coins in five days, Yosaku will be imprisoned and Yuki taken away to “serve” the Bailiff. She will have to draw upon her long-dormant powers as Yuki-Onna in order to save the day.

The Snow Woman is a very worthy addition to the folk tale popularized in Kwaidan. In Snow Woman, Yosaku and Yuki (in her human incarnation) are both orphans, which makes their attraction to one another all the more understandable and poignant.

Making Yosaku not just a simple woodcutter, but an apprentice to a master wood carver and an artist in his own right is a clever enhancement. There is dramatic tension between Yosaku’s idyllic life with a beautiful wife and handsome son, and the burden of being tasked with carving a major religious statue. It’s not a task for the faint-hearted -- Yosaku spends several years waiting for the wood to cure to a perfect state, all the while trying to envision the perfect representation of the goddess.

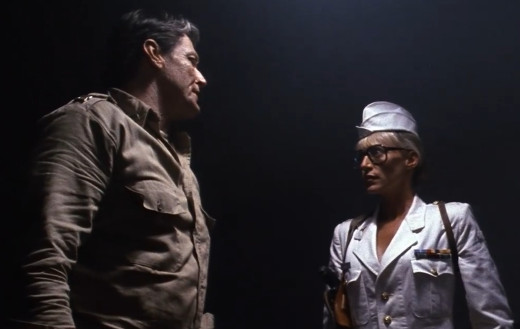

|

| The Bailiff is up to no good. Some people are never satisfied with what they have. |

The addition of a human antagonist in the form of the Bailiff heightens the drama as well. Yuki travels to the capital to plead for clemency, and as folklore luck would have it, the Lord she wishes to see has a young son on the brink of death. In an especially beautiful and ironic scene, she summons up her spirit powers and uses the snow and cold for good, to tamp down the boy’s fever, rather than to kill. Her reward for saving the boy’s life is enough to buy her and Yosaku’s freedom.

But Yuki is not quite done saving the day, if only accidentally. Even with his freedom secured, Yosaku is struggling to finish the statue. The only thing left to complete is a face worthy of a goddess, but the artist is not sure he’s up to the task. It doesn’t help that the Bailiff has convinced the head priest to enlist another master craftsman to carve a statue in competition with Yosaku. In another ironic twist, it will take Yosaku breaking his oath to the Snow Woman, and Yuki-Onna’s last act of mercy and compassion, to provide the inspiration to complete the statue.

Like Kwaidan, Snow Woman is the sort of film where it feels as if you could stop it arbitrarily at any point, print the frame, and have a beautiful work of art for your troubles. With the extended runtime, The Snow Woman makes several memorable appearances, and is even more impressive and terrifying than in the earlier film.

|

| "Don't look her in the eyes! Oops, too late!" |

Chikashi Makiura’s cinematography is hauntingly beautiful, especially in the snowy nighttime sequences where the Snow Woman seems to float over the landscape. Her mere presence causes objects and people to freeze. Once you look into those unearthly eyes, you're a marked man.

In striking contrast to the Snow Woman’s frozen domain, there are a couple of scenes at the shrine, where an old shaman, standing in front of a huge cauldron of boiling water and brandishing a stick with streamers attached to the end, is conducting a purification ceremony. As he flicks the stick to and fro with flames dancing around him, he looks like a particularly malevolent denizen of some obscure corner of Hell.

Yuki, who is attending the ceremony with her husband and son, is definitely not in her element. Even though Yuki is obscured by the crowd, the shaman recognizes her for what she is, and violently shakes drops of boiling, purified water at the ghost who is desecrating the ceremony. Yuki recoils and withdraws like a vampire from a cross. The scene is violent and loud, lit up in fiery oranges and reds, a notable counterpoint to the cold, snowy landscape that predominates in other parts of the film.

|

| You can't slip a ghost past this scary old shaman. |

The Snow Woman tale was remade as recently as 2016. I haven’t seen that version, but it's hard to imagine one better than the 1968 film. I’m betting that folklore fans will be entranced, and lovers of contemporary Japanese horror will appreciate the visual style of this venerable cinematic ancestor.

Where to find it: Stream it here, or check out Sinister Cinema for a very crisp, good-looking DVD copy worthy of the beautiful cinematography.