Pros: Solid cast; Typically fine Hammer production values; Michael Ripper almost steals the show as a gleeful undertaker.

Cons: The marsh phantoms don’t get enough screen time; Oliver Reed and Yvonne Romain are consigned to bland secondary roles.

This post is part of the Rule, Britannia Blogathon, hosted by classic film buff, TV historian and author Terence Towles Canote at his blog, A Shroud of Thoughts. The rules are simple: simply write about any British/UK film made before 2011. That I can do!

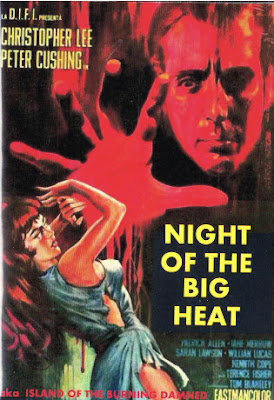

Hail Britannia! During the 1950s and early ‘60s, when American B filmmakers couldn’t get enough of irradiated sci-fi menaces of every size, shape and description, and were reimagining traditional Gothic monsters by giving them sci-fi origins (Blood of Dracula, The Werewolf, The Vampire), the British film industry, and Hammer Films in particular, was gearing up to add fresh Gothic takes on all kinds of genres.

Hammer jumped into the ‘50s sci-fi craze like everyone else, but whereas American sci-fi thrills generally played out in broad daylight, much of Hammer’s output -- Four Sided Triangle (1953), The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), X the Unknown (1956) and The Abominable Snowman (1957) -- was shrouded in night and shadows, with surroundings that the classic monsters would have been very much at home in.

Then, starting in the late ‘50s, Hammer took those same monsters, lit them up in brilliant Technicolor (and Eastmancolor) and gave them new life. By 1962, Dracula, Baron Frankenstein, the Mummy and even a silver-haired werewolf had trod the boards at Hammer’s Bray studios.

|

| Back in the day, this set my geeky little heart to beating fast. |

While Hammer is justifiably remembered for its colorful takes on the classic monsters, the studio delved into all sorts of genres in its bid to lure audiences away from the telly. Throughout the ‘50s, the studio churned out dozens of crime dramas, period pieces, war pictures and even a handful of comedies.

In the early ‘60s, the sensational success of Hitchcock’s Psycho set the studio scrambling to capitalize on the psychological horror craze with films like Scream of Fear (1961), Paranoiac (1963), and Maniac (1963).

And bless their hearts, even as the decade was advancing inexorably toward its date with the youth movement and flower power, Hammer was still greenlighting swashbucklers and pirate movies long after most other film companies had abandoned the genre.

Night Creatures (aka Captain Clegg, 1962) had more of a circuitous route to getting on the silver screen than most Hammer pictures, and partly as a result, the marketing emphasized its rather mild horror aspects. In the UK, it was released under the title Captain Clegg and was paired with Hammer’s version of The Phantom of the Opera; in the U.S. it became Night Creatures, and was the bottom half of a double bill featuring Hitchcock’s The Birds. (More on that later…)

The horror elements are frontloaded into this modestly budgeted swashbuckler. In the prologue (captioned 1776), a brutish sailor (Milton Reid) has been brought before the captain (whose face we never see), charged with having assaulted the captain’s wife. For this crime, he’s sentenced to have his ears slashed and his tongue cut out, and then banished to a remote island with no food or water.

Fast forward to 1792, where, back on the mainland, a lone figure is furtively making his way across desolate marshlands in the dead of night. He’s stopped in his tracks by the sight of demonic glowing skeletons on horseback, and in terror he flees and then trips and collapses in a heap in front of a scarecrow. The scarecrow suddenly opens its eyes and glares down at him. Now thoroughly freaked out, the man backs into a brackish swamp, which swallows him up.

|

| "We only wanted to ask him if this was the way to Bray Studios!" |

We soon learn that the unfortunate victim was an informer for the Crown who had been reporting on possible smuggling activities in the coastal marshes near the village of Dymchurch. The smuggling rumors bring a squad of the King’s men to Dymchurch led by the brash and cocky Captain Collier (Patrick Allen).

At this point, Night Creatures settles down (comparatively speaking) to a cat and mouse game between the villagers (who are definitely up to no good, at least from the authorities’ perspective) and the King’s agents.

Collier tries to intimidate the town by striding imperiously into the church where the dynamic vicar Dr. Blyss (Peter Cushing) is conducting services. Blyss invites him to stay for the rest of the sermon, if he will only remove his hat. Collier snaps back that while he serves the King, the hat stays on.

Outside, in a meet and greet with the Captain in the churchyard, Blyss plays to Collier’s ego by telling him what an honor it is to meet a hero of the empire. Standing over the grave of the notorious Captain Clegg (the merciless captain in the prologue), Collier puffs himself up:

Collier: I flatter myself that I gave him a run for his money.

Blyss: But you never caught him Captain.

Collier: Yes that’s true, but how did you know?

Blyss: He was hanged at Rye, I attended his last rites as prison chaplain.

Collier: Last rites? I suppose he repented all his sins at the last moment?

Blyss: He died a Christian. I proceeded to give him a Christian burial here at Dymchurch.

Collier: Well if I’d have caught him he’d have had a different end. I’d have had him hanged, drawn and quartered, publicly too.

Blyss: I’m sure you would, but then you didn’t catch him, did you?

|

| The first round goes to Dr. Blyss. |

After the exchange, Blyss, who is in charge of more than just the church, meets with his right hand men, Mipps the undertaker (Michael Ripper) and Rash the innkeeper (Martin Benson), and coldly orders that the villagers deny Collier’s men any quarters.

Much of the movie consists of Dr. Blyss and his band leading Collier and his men around by their noses while unctuously pretending to serve them. They employ secret passages, Mipps’ coffins to ferry around the contraband, men disguised as scarecrows to spy on outsiders, and of course, the eerie marsh phantoms to scare off would-be informers and distract the King’s men.

But Collier is not without brains and resources, including the brute man seen in the prologue, whom he uses like a drug-sniffing dog (!!) (The man had been rescued from the island by a passing English ship. While he is crude, mute and repulsive to look at, he’s not entirely unsympathetic, and he figures prominently in the rousing denouement.)

Night Creatures is slowed down somewhat by a bland romantic subplot involving foppish Harry (Oliver Reed), son of the wealthy squire, and Imogene, the tavern maid (Yvonne Romain). The two had been used to much better effect the year before in Curse of the Werewolf. At least Harry has the honor of being wounded in the line of duty.

|

| "I now pronounce you a mundane romantic subplot." |

A somewhat harsher fate awaits Rash, who is aptly named. In the time-honored tradition of B-movie creeps, Rash, who is also Imogene’s guardian, stumbles on a secret involving the blushing, beautiful maid and decides that he wants her for himself. Although he is Blyss’ lieutenant, the good doctor becomes suspicious of the fretful innkeeper, and the question of whether Rash will stay true to his comrades or give them up provides additional suspense.

Michael Ripper, who was a standard fixture at Hammer, almost steals the show as the slyly servile undertaker Mipps. With unnaturally rosy cheeks not unlike a fresh cadaver made up for an open casket funeral, Mipps wears an all-knowing grin while he misdirects Collier and spars with the dour innkeeper. There’s a great scene where Rash rushes into the undertaker’s workshop to warn him that Collier and his men are approaching, and is startled when Mipps suddenly sits up in the coffin where he’d been sleeping.

|

| "Let's get to it men! We've got to deliver those kegs to the fraternity house before nightfall!" |

Of course the main event is the battle of wits between the duty-bound Captain and the wily vicar. It’s a credit to the film that both characters have their talents and faults (huge egos among them), and neither is a cardboard bogeyman. For much of the movie, Blyss is the chess master moving his pawns around, always several moves ahead of Collier, who seems to be more of a checkers kind of guy. But the Captain’s perseverance forces a final, fateful confrontation (and an opportunity for Cushing/Blyss -- and his stunt double -- to demonstrate buccaneering skills by swinging from the rafters and engaging in a lengthy, thrilling fight scene).

While some might wish the film had done more with the creepy marsh phantoms and less with the verbal repartee, it’s still a good adventure yarn with a cast of talented regulars and the studio’s signature production values. Hammer had a knack for making its modestly budgeted Gothic horrors and historical dramas look like a million bucks.

Where to find it: Streaming | Blu-ray (8 film collection)

Secrets of the Marsh Phantoms #1: Night Creatures’ path to getting made had more twists and turns than a smuggler’s secret passageway. Major Pictures, which had secured the rights to a 1937 film adaptation of Russell Thorndike’s novel Doctor Syn -- A Tale of Romney Marsh (1915), came to Hammer with a proposal to do a re-make. Hammer promptly got into a legal dispute with Disney, which had gotten the rights to Dr. Syn directly from Thorndike’s publisher to do their version, which aired in the U.S. as a 3 part mini-series, The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, on The Magical World of Disney in Feb. 1964.

As Marcus Hearn and Alan Barnes relate in The Hammer Story, “[Hammer] arrived at a compromise with Disney in mid-September: Hammer could make their version of Thorndike’s story, but they were forbidden to use ‘Dr. Syn’ as either the name of a character in the screenplay or as the title of the film itself. [Producer] Anthony Hinds cancelled an imminent holiday and hastily rewrote [the] first draft, removing all references to Dr. Syn and naming Thorndike’s undercover pirate Dr. Arne. (Peter Cushing was so enthused by the project that he also wrote a screenplay, Doctor Syn, based on the books.)” Further delayed by union troubles, the production finally got underway in September of 1961, with Dr. Arne renamed Dr. Blyss in the final draft. [Marcus Hearn and Alan Barnes. The Hammer Story: The Authorized History of Hammer Films, Titan Books, 2007, p. 70]

Secrets of the Marsh Phantoms #2: Hearn and Barnes again: “The film was lent a supernatural atmosphere by the inclusion of the ‘marsh phantoms,’ which were heavily promoted in the film’s publicity. ‘We painted black body suits for both the horsemen and the horses with codit reflective paint,’ recalls special effects assistant Ian Scoones. ‘Two film spotlights were placed either side of the camera lens, giving a bright, luminous effect…’

Scoones loaned Hammer ‘François,’ a human skull he discovered in ‘Dead Man’s Island,’ unconsecrated Kent marshland where the Admiralty buried French prisoners of war: ‘It is François, illuminated with codit paint, zooming up to the lens that drives the fleeing Sydney Bromley [the unfortunate informer] into the swamp…” [Ibid., p. 71]

Secrets of the Marsh Phantoms #3: Night Creatures, the title that Universal-International used for the U.S. release, was previously attached to a Hammer project to adapt Richard Matheson’s novel I am Legend to the screen. The British Board of Film Censors nixed the project, and since Hammer had promised Universal a ‘Night Creatures’ movie, Captain Clegg got stuck with the title.

|

| "Are you sure this is going to be enough for the party?" |