Now Playing: Nightmare in Wax (1969)

Pros: A couple of brief but genuinely chilling sequences; A surprisingly solid "method" performance by Cameron Mitchell

Cons: Rock-bottom production values; Irritating, amateurish music score; Unfunny comic relief; A bizarre WTF? ending

Extra special bonus: After reading this entertaining and compelling post, get yourself over to She Blogged by Night for more entries in the Camp and Cult Blogathon!

Pros: A couple of brief but genuinely chilling sequences; A surprisingly solid "method" performance by Cameron Mitchell

Cons: Rock-bottom production values; Irritating, amateurish music score; Unfunny comic relief; A bizarre WTF? ending

Extra special bonus: After reading this entertaining and compelling post, get yourself over to She Blogged by Night for more entries in the Camp and Cult Blogathon!

I have a problem. (Okay, I have more than one problem, but for your sake, dear reader, I'm only going to admit to one today.) I am an inveterate collector (i.e., a spineless consumer who can't help but buy all kinds of stuff that ends up collecting dust on a shelf somewhere… or is that "invertebrate collector"? Whatever.) In this age of instant-play-streaming-recordable-downloadable everything, I still like (heaven help me) admiring the garish cover art as I pop open a DVD case for the first time and struggle to free the shiny disc from its plastic imprisonment. (Similarly, swiping e-book pages on a iPad is just not the same as blowing the dust off that old hardcover and licking your fingers as you page through it.)

I suppose it boils down to this: if it's too easy to acquire and use, then you don't appreciate it as much. Plus, there's that urge to own that I just can't shake. Even if I decide to buy instead of rent that Amazon Instant Play title, they store it for me in a network cloud somewhere. My confidence is not exactly boosted by some digital scheme that takes as its metaphor a puffy, ephemeral thing in the sky that is here one minute and gone the next. And then there's wretched Netflix, which can't seem to negotiate any sort of stable, reliable access with its content providers for more than a few months at a time.

And then there's the whole issue of bandwidth and those inevitable [expletive deleted] moments when you're trying to watch something over the danged internet. Like 47% of my fellow Americans (source: the Romney campaign), I live in a moderately dinky town out in the sticks where "fiber optics" means putting on your reading glasses to check out the Metamucil dosage directions, and where the most up-to-date transmission lines were laid about the same time that the Pony Express made its last stop in town. I just cannot get those danged Netflix instant titles to stop flickering no matter how many times I upgrade my danged internet service and HDMI cable. [Expletive deleted!!!]

In such a spotty network environment, it's still easy (at least for me) to be old school. There are a few upsides to the inevitable march of technology. As the venerable DVD player goes the way of the VCR and the Dodo, there are lots of great deals to be made on those shiny, fragile discs. A couple of months ago I was at the last store in town that rents DVDs, reflexively burrowing through the discount bin (for those of you not familiar with this sublime experience, it's a cross between panning for gold and trying to dig for some trinket using one of those crane things that you stick a bunch of quarters in).

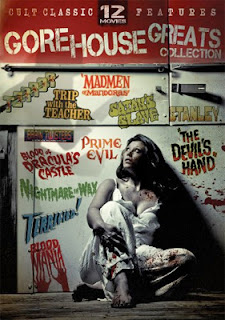

|

| This woman is exhausted after watching 17 straight hours of gory entertainment! |

Let me say at this point that I am not by nature a sneaky person. But then, neither am I a complete fool. So I generally don't come home with these bargain bin treasures and wave them in my long-suffering wife's face, saying, "Hey, look what I found!" Every so often, they stay safe and secure under a coat or umbrella in the back seat of the car, and then leisurely wander into the house later in the evening. Still, my wife is very intelligent, has a steel-trap memory, and incredibly sharp eyes. Far and away the most frequently spoken sentence in my house is "Where did that come from?" I'm sure she has visions of those houses where you can just barely get from room to room using narrow passages carved out of towering stacks of old newspapers, books, magazines, and DVD cases. But that can never happen-- I have a steady state collection. As I bring new DVDs in, I make a list of old stuff that I need to trade-in or donate to Goodwill. And one of these days I'll get around to it.

Anyway, back to the Gore House Greats (gotta love that title!). Perusing the list of titles on the back of the case, several jumped out at me, their fangs bared and their hideous claws scratching at the very large portion of my brain allocated to cheesy B horror and sci-fi movies. There's The Madmen of Mandoras (aka They Saved Hitler's Brain; 1963), which I haven't seen, but which is supposed to give Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) a run for its money as one of the worst films of all time; Al Adamson's Blood of Dracula's Castle (1969), one of the several thousand B horrors John Carradine appeared in (I'm not exaggerating by much); The Devil's Hand (1962), a decent occult thriller starring Alan's dad Robert Alda; and then there's Nightmare in Wax.

I had just read some interesting accounts of the making of Nightmare by a couple of cast and crew members in Tom Weaver's A Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde, (McFarland, 2010), so I revved up the old DVD player to check it out. As I was watching it, I experienced a mild feeling of deja vu-- somewhere in the dim dark past, I probably caught this thing on the late show or through a moment-of-weakness videotape rental. My second reaction was, this is probably not the gem of the collection-- even something that calls itself "Gore House Greats" and features such titles as Blood of Dracula's Castle and Satan's Slave.

Nightmare in Wax isn't even a gem in the rough. It features story elements that were getting a bit long-in-the-tooth in the 1950s (not to mention the late 1960s), lines of dialog that are head-slappingly inane, rock-bottom production values, and acting that ranges from high-school amateur to pretty good. However, it does have its moments, which I will get to later.

The story will seem familiar to anyone who's seen Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) or House of Wax (1953). Vincent Renard (Cameron Mitchell) is Paragon Studios' greatest makeup artist. He's so supremely self-confident that he is dating the studio's biggest female star, Marie Morgan (Anne Helm). When they announce their engagement at a swank Hollywood cocktail party, the jealous, piggish studio head Max Black (Berry Kroeger) tosses a drink into Vincent's face just as he's lighting a cigar. The alcohol turns the lighter into a impromptu flame thrower, setting fire to poor Vincent's head. He crashes through a plate-glass window and dives into the backyard pool.

|

| After the "accident," Vincent (Cameron Mitchell) refuses to be consoled by his ex-fiance (Anne Helm). |

Following Vincent's "accident," Paragon Studios seems to have fallen under a curse. Several of its big name actors (and one actress) have turned up missing. Hollywood detectives Haskell (Scott Brady) and Carver (John "Bud" Cardos) are assigned to investigate, and leaving no stone unturned, pay the disgruntled makeup man turned eccentric wax sculptor a visit. The museum has exploited the notorious disappearances by featuring an impressive wax figure tableau of the missing Paragon stars. Of course, the police detectives are not exactly Holmes and Watson, and leave the museum figuratively scratching their heads.

While paying homage to its cinematic wax museum predecessors (especially with the horribly wronged, disfigured mad artist main character), Nightmare updates the familiar story with a pseudo-sci-fi plot device-- a nerve agent that can put human beings into a very rigid state of suspended animation. As if that weren't enough, we learn in Bill-Nye-science-guy fashion that any kind of electrical discharge -- like a lightning storm -- can interfere with the nerve agent's effects. Uh-huh. It's so Saturday-morning-cartoonish, that killing someone and using the corpse as the basis for a wax figure sounds very plausible by comparison. As you might expect, a standard-issue horror film electrical storm figures into the film's climax (as well as a cringe-inducing comic relief sequence in which a museum guide thinks he sees one of the wax figures blinking at him and swears to lay off the booze… oh boy!)

At the root of Nightmare's faults is the obvious cheapness of the production. Characters who are supposed to be fabulously wealthy studio executives, actors and actresses lounge around in very modest LA homes. Wax heads are obviously actors with their heads sticking out of tables, trying very hard to be still. And the music score sounds like it was put together using tracks from a couple of Halloween sound effects CDs.

|

| Whatever you do, don't let this guy give you a seasonal flu shot! |

However, at least one of Nightmare's crew members didn't appreciate Cameron Mitchell's style, acting or otherwise. Real makeup man Martin Varno had nothing but bad things to say about Mitchell in his interview with Tom Weaver:

He was a complete jerk. I'm sure you've heard that before. He was probably real pissed-off that he wasn't doing big pictures at Fox any more. … There was a scene where Cameron, who was supposed to be this great makeup man turned wax sculptor, was sitting at a table making up what was supposed to be a wax head. [Producer Rex] Carlton said to me, "Hey, Can we use your makeup case in the scene?" My makeup case was a wooden fishing kit that I had bought and fixed up… I said "Look, this is how I'm making my living now. Be careful with it, don't let him throw Technicolor blood all over it or something." So they started shooting the scene and there on the table was my makeup case, as if it were his, and on another part of the table were my different bottles of stuff and my brushes and sponges and things. When they started shooting, he began being "dramatic," he began being The Actor, and within the scene he got angry about something-- and he decided to extemporize a little bit and surprise us all, and he slapped all the bottles off the table and also pushed my whole makeup case off the table onto the floor. Smashed God knows how much. Because he was "act-ing"… (Ibid.)Well, makeup cases come and go, but great film acting is forever. (Anyway, Varno was compensated for the damage.) By 1969, Mitchell's A-list film days were indeed behind him. Mitchell soared to fame playing Happy Loman in the stage and film versions of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Through the '50s and '60s, he appeared in dozens of westerns, war dramas, and costume epics. The high point of his TV career came in the late '60s on the western The High Chapparal, where he played the very popular character Buck Cannon. Other sci-fi/horror roles include Flight to Mars (1951) and Mario Bava's gruesome Blood and Black Lace (1964).

Writer-Producer Rex Carlton (the guy who reimbursed Martin Varno for his damaged makeup case) was also responsible for a couple of low-budget sci-fi classics discussed in this blog: Unearthly Stranger (1964; writer) and The Brain That Wouldn't Die (1962; producer). An IMDb trivia blurb states bluntly that "He killed himself after being unable to reimburse the mob for money he borrowed to finance another picture." (?!) This happened before Nightmare in Wax was released.

One last warning. Be careful what you have in your hands as you watch the final scene, because you might just throw it at the screen. But don't let that deter you from experiencing one of the more bizarre, "immerse yourself in the character" method-style performances in the history of low-budget horror movies.

Makeup artist turned wax sculptor Vincent Renard (Cameron Mitchell) has an interesting conversation with one his creations: