Pros: Lavish costumes and sets; old-school spectacle

Cons: Cliched plot recycled from the silent era; A.I.P.'s dubbed, condensed version offers little pathos and even less suspense

Art is a fickle mistress. She laughs at our pretensions of greatness, and chuckles at our struggles to be simply competent. She favors the young, and often showers them with great gifts, but before you can blink she's packing her bags and moving on to the next upstart. Although movies aren't her all-time favorite medium, she has paid regular visits to their creators over the decades.

Although the great Fritz Lang never thought of himself as an artist, he had more than his share of flirtations with the muse. In his first go-round in Germany between the World Wars, Lang helped establish the film grammar that we know today, invented big-budget, effects-laden cinematic sci-fi, laid the expressionist groundwork for later film noir, and… oh yeah, made a couple of the greatest films of all-time, Metropolis (1927) and M (1931).

Then along came the Nazis, and Lang's famous flight from Germany in the dead of night after an ominous meeting with propaganda minister Goebbels. After a couple of years in Paris, Lang ended up in Hollywood. In this strange new culture, with its much different way of making movies, it appeared that the muse had deserted Lang for good. Even though he kept very busy, making over 20 movies in the next couple of decades, critics of the time generally agreed that he had lost it.

While he certainly made some mediocre films during his Hollywood period, time has been a lot kinder to Lang than his contemporary critics, who seemed to be itching to dismiss everything that the eccentric German emigre did in his adopted country. Lang's resume from this period reads like a "Best of Film Noir" list: Ministry of Fear (1944), The Woman in the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945), Clash by Night (1952), The Blue Gardenia (1953), The Big Heat (1953), Human Desire (1954), While the City Sleeps (1956), and his last film made in America, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956).

Deprived of the near endless resources he was accustomed to in Germany and struggling against a strange culture, Lang nonetheless made a string of great movies that would come to define the film noir genre. We can admire Metropolis for its epic sweep and its groundbreaking technological achievements, but the smaller, more personal films like Scarlet Street and The Big Heat are so much more gut-wrenching and emotionally-involving, and are as great in their own way. Along with the young, it seems that Art often comforts the afflicted.

By the mid-1950s, Lang had had it with the meager trickle of low-budget film offers and Hollywood's crude philosophy that you're only as good as your last box-office success. He started traveling, first to India, which had held a unique fascination for him, and then to Germany (the first visit since his escape from the Nazis before WWII). He talked to the German press about possibly making one last film in his former home country, but initially nothing came of it. Then, Producer Artur Brauner, a Polish Jew who also had managed to escape the Nazis, but who had returned to postwar Berlin to set up a studio, convinced Lang to take one more stab at cinematic glory.

Lang had more than a passing fancy for the proposed project, a remake of Das Indische Grabmal (The Indian Tomb; 1921). Based on a novel by actress/writer Thea von Harbou (whom he married), Lang helped von Harbou develop the script under the auspices of one of the legendary founders of German cinema, Joe May. Lang was in high hopes of directing, but when May took over the directing reigns, he was devastated. According to Lang biographer Patrick McGilligan, Lang saw Brauner's offer as a sort of "closing of a mystical circle" and a chance to remake his fate 40+ years after his first great disappointment. (Patrick McGilligan, Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, St. Martin's Press, 1997)

As in 1921, the epic story was divided up into two parts, Der Tiger von Eshnapur (The Tiger of Eshnapur) and Das Inische Grabmal. Millions of German marks were committed by a studio that had up until then specialized in low budget projects. The normally uncompromising Lang compromised with his producer on the choice of cameraman (Richard Angst over Lang's favorite, Fritz Wagner), and on the female lead of Seetha. Lang wanted a native Indian, but grudgingly accepted the beautiful, but thoroughly American, Debra Paget because of her greater box office potential.

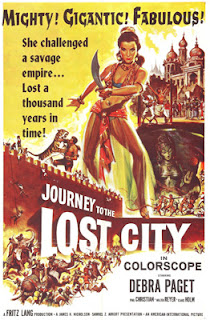

The films were mercilessly panned by German critics upon their release in 1959. One Austrian went so far as to call them "an orgy of trash and kitsch." (Ibid.) But apparently there was still an audience for kitsch recycled from the silent era, as they made quite a bit of money in other parts of Europe. American International Pictures acquired the U.S. rights, combined the two films into one drastically edited version, dubbed it in English, and released it in the states as Journey to the Lost City in late 1960. In effect, A.I.P. took a grand, two part costume epic and turned it into a 94 minute B movie suitable for a drive-in double-bill (albeit with better production values and fancier sets).

|

| The star-crossed lovers tempt fate by meeting in the jealous Prince Chandra's palace. |

When Chandra learns that Harald is seeing his bride-to-be behind his back, he changes from a beneficent, kindly ruler to an angry, vengeful autocrat. The Prince condemns Harald to the palace tiger pit, but throws him a spear in a gesture of grudging respect. The architect and man's man kills yet another tiger, and later he and Seetha manage to escape into the desert. Chandra commands his double-dealing brother to bring them back. In the meantime, Harald's kindly Indian assistant has traveled to New Delhi to warn Harald's sister and brother-in-law (Sabine Bethmann and Claus Holm) that Berger is in grave danger from the spurned and vengeful Prince. They hightail it to Eshnapur to find out what's going on. Little do they know that they're rushing headlong into a deadly palace coup.

|

| A mummified soldier guards the catacombs deep below the Prince's palace. |

Still, it is a film by the great director, the second to last one he directed (the underrated The 1,0000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, 1960, was his swan song), and for that alone, it's inherently interesting. Also interesting, at least to me, is the presence of Debra Paget and Paul Hubschmid/Christian. In my humble opinion, Debra is one of the most beautiful women ever to appear in movies. Even miscast as an Indian dancer, she is a striking, alluring presence-- check out the clip below and see if you don't agree. Debra started out playing exotic roles in a variety of westerns and costume dramas -- Broken Arrow (1950), Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), The Ten Commandments (1956) -- but equally interesting (and a lot more fun) were a string of horror and sci-fi roles as her career wound down: Most Dangerous Man Alive (1961), Tales of Terror (1962), and one of my all-time favorites, The Haunted Palace (1963).

The Swiss-born Paul Hubschmid had a brief Hollywood stint as Paul Christian in the late 1940s - early '50s. He starred in another one of my all-time sci-fi favorites, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953), before returning to Europe for good.

The two films from which Journey was derived were to be Lang's capstone achievements, and a vindication for him. By most accounts, they were significantly less than that-- further proof that you can't go home again. Still, Journey is a interesting footnote in the varied and fascinating career of a great artist and craftsman. In the words of screenwriter Werner Luddecke, Lang was "[A] perfect worker, a perfect architect, a perfect tyrant, a perfect listener, critic, and furthermore, a man who could withstand criticism." [McGilligan].

An imperfect copy of Journey to the Lost City is available on DVD-R from Sinister Cinema, and on Amazon Instant Play. You might want to check it out anyway.

All eyes are on Seetha as she dances in the temple:

No comments:

Post a Comment