Now Playing: The Psychopath (1966)

Pros: Colorful, quirky characters; Nicely staged climax and a particularly creepy ending

Cons: Some egregious over-acting; Pointless lovers' subplot slows things down

Pros: Colorful, quirky characters; Nicely staged climax and a particularly creepy ending

Cons: Some egregious over-acting; Pointless lovers' subplot slows things down

What is it about dolls that causes an involuntary shudder in many of us? Have you ever been in a toy store, or worse yet, a semi-darkened room, and seen a particularly hideous specimen propped up in the corner, its stubby plastic or porcelain fingers almost seeming to move, its sightless glass eyes staring at you? Have you ever thought to yourself, or said half-jokingly to the person standing next to you-- "that thing frightens me!"

In an earlier post on the TV movie Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981), I speculated that somewhere in the deepest, darkest recesses of the Id, we all harbor the atavistic belief that figures made to look like a man or an animal can somehow be invested with the spirit or power of the thing being represented. The most obvious example of such sympathetic or imitative magic is the voodoo doll, which can be used to gain power over the person depicted.

Then there's the spooky feeling you get when you happen to glance into the black cutout holes that are supposed to be the scarecrow's eyes, or the fixed, staring glass eyes of a doll, and for just the briefest moment you think you see some sort of life there, possibly malevolent. Filmmakers have been playing on this atavistic fear for a very long time. There have been possessed dolls (Trilogy of Terror, 1975; Dolls, 1987; Child's Play, 1988), possessed ventriloquist's dummies (Dead of Night, 1945; Devil Doll, 1964; Magic, 1978), possessed puppets (Asylum, 1972; Puppetmaster, 1989) and even people that have been turned into dolls (The Devil-Doll, 1936).

A recent and very funny example of this fixation is an ad for the U.S. postal service, in which the ever-helpful mailman assures a frightened family that they can quickly and economically return a creepy clown doll that seems to have a life of its own:

Dolls figure very prominently in the eerie atmosphere of The Psychopath, but in this case they are not possessed themselves, but rather are the tools of a person possessed by madness. The film begins with a well-dressed man carrying a violin case preparing to get into his car, then discovering to his great irritation that it has a flat tire. Shrugging his shoulders, he starts walking. As he wends his way through dark alleys, apparently looking for a shortcut to his destination, we see several quick shots of a small red car following him. He pops into yet another alley, then, realizing it's a dead end, turns around. The car's high beams hit him like a slap in the face, and he throws an arm up to shield his eyes. Trapped in the dead-end alley, he drops his violin and waves his arms frantically as the car bears down on him. We see the violin case crushed under the car's tires, then flattened a second time as the car lurches forward and backs up again. As the car screeches off, the unseen driver drops a doll -- an exact replica of the victim down to his coat and tie -- onto the smashed remnants of the violin case.

Cut to a genteel, well-appointed drawing room, where we see a close-up of an empty chair with sheet music lying on it. The camera tracks back to reveal three well-heeled men playing a nice classical piece for string quartet. We know what's happened to the fourth member. The stark contrast of the dark, grimy alley where the murder occurs to the well-lit, refined atmosphere of wealthy privilege is nicely done, along with the subtle reveal of the victim's intended destination.

As the quartet "jam" session is breaking up, police inspector Holloway (Patrick Wymark) shows up at the residence with information that their fourth member had been found murdered at 8 that evening -- run over by a car several times. He starts grilling the assembled amateur musicians and other guests about their whereabouts, and they furnish him with a variety of alibis for the 8 o'clock hour. In an odd bit of business, the inspector lets them have their say, then reveals as he gets up to leave that the body was only found at 8 o'clock-- the coroner had determined time of death at around 7.

|

| Inspector Holloway (Patrick Wymark) interviews the widow Von Sturm (Margaret Johnston) surrounded by her "friends" |

Pretty soon we find out that the upstanding citizens and amateur musicians that Clemmer had been friendly with were -- you guessed it -- members of the very commission that condemned Von Sturm and seized his extensive holdings. There are rumors that the commission manufactured the evidence against the industrialist to get their grubby mitts on his money. And yes, you guessed it again-- soon they're bumped off one by one, each murder scene, like Clemmer's, marked with a doll uncannily fashioned to look exactly like the victim. To add variety to the proceedings, each self-satisfied ex-commissioner is dispatched with a different method-- by car, poison, hanging and **gulp** blowtorch. Another potential witness is stabbed to death, and the police inspector himself is almost blown up in his own car.

|

| Martin Roth (Thorley Walters) stares into the face of death: a doll uncannily fashioned in his own likeness. |

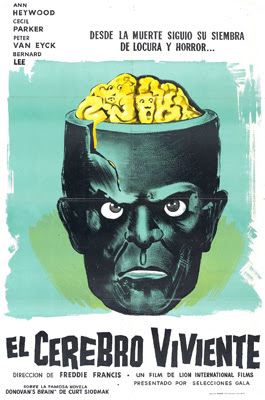

The strength of The Psychopath is not in a "keep 'em guessing" mystery plot, but in the well-crafted creepy atmosphere and eccentric characters (due in no small part to the talents of director Freddie Francis and cinematographer John Wilcox). There's the imperious businessman Frank Saville (Alexander Knox) who wears his smug self-satisfaction with the same panache that he wears his elegant smoking jacket. There's the portly, nervous solicitor Roth (Thorley Walters) who jumps at the sight of his own shadow. Robert Crewdson plays the debonair sculptor Ledoux with a thick French accent and heavy dose of insouciance. Mark (John Standing), the industrialist's son and professional mama's boy, is immaculate with his perfect blonde haircut and tight-fitting black leather jacket. When he grins at the inspector, you know there's something not quite right with that boy. But the eccentric prize (a big honey-baked ham) goes to the widow Von Sturm (Margaret Johnston), who goes from cooing at her large collection of dolls, to weeping uncontrollably, to rolling her eyes and gnashing her teeth. It's either fun or appalling to watch depending on your frame of mind.

|

| Mother and son have a heart-to-heart talk. |

In the midst of all these bizarre characters, Patrick Wymark's Inspector Holloway is an island of calm, unflappable British reserve. It's a good acting job and a nice touch, with the quiet competence of the Inspector standing in stark contrast to the hysterical aberrations of the other characters.

Also noteworthy is Elisabeth Lutyen's original music-- the simple, chilling nursery music for a madhouse is used very effectively in the titles and at key points in the film.

While more than a few precious minutes of film time are wasted on an uninteresting side story about Saville's disapproval of his daughter's American fiancee, and there are parts that get overly talky, you'll want to stick it out for the nightmarish conclusion. Without spoiling it, let's just say that, like Psycho, this film manages to raise the gooseflesh with a simple (?) shot of a person sitting in a chair. Overall, The Psychopath is a very worthy member of the Psycho-imitators club, bringing a number of unique, creepy touches and stylistic flourishes to the subgenre.

Sadly, this one is very hard to find, and there's no U.S. DVD release that I'm aware of. I saw it on TCM Underground (Friday nights). At the moment, the full movie is available on YouTube (see below). Catch it before some grumpy rights-holder forces YouTube to take it down.

Where to find it:

YouTube