Now Playing: The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957)

Pros: Brave attempt to mix Gothic horror and "reform school girls" genres; Interesting plot and character touches somewhat redeem an absurd premise

Cons: Flat direction; largely mediocre acting; Some "slap your forehead" plot absurdities; Weak "monster" & makeup

Pros: Brave attempt to mix Gothic horror and "reform school girls" genres; Interesting plot and character touches somewhat redeem an absurd premise

Cons: Flat direction; largely mediocre acting; Some "slap your forehead" plot absurdities; Weak "monster" & makeup

Just like the Queen in Snow White, I have a magic mirror that flatters the heck out of me every morning when I manage to haul my aching carcass out of bed and stumble into the bathroom. It's one of those jobs with a row of warm-colored globe lights on top. The magical light flattens out most lines and wrinkles, hides my turkey neck in shadow, and even manages to soften the white, bristly old man hair sticking out in all directions. For just a brief moment as I stand there shaving, I can imagine that I'm 10, maybe even 15 years younger. (No, I'm not going to reveal my age, because then I'd have to track you down and kill you. Nothing personal of course.)

Unfortunately every other mirror that I encounter in that cruel world out there adds 5 or 10 years under the merciless glare of cold fluorescent light. And forget about photographs! Every time I see a photo of myself, I immediately think, who is that old wreck standing next to [fill in the blank]?

Yes boys and girls, it's no fun to get old. So it's no wonder that mythology, and modern mythology in the form of B movies, is filled with people trying to cheat death and find the secret of eternal youth. Quite often, seeking eternal youth becomes complicated… and deadly. My advice is to get a good vanity mirror. It costs less, is easy to maintain, and doesn't require you to sell your eternal soul.

The Man Who Turned to Stone tells the strange tale of a group of old men (and one woman) who ruthlessly exploit nubile young women to regain their youth and vitality (come to think of it, that's just a typical day in Hollywood!).

A newly hired staff counselor at the LaSalle Detention Home for Girls, Carol Adams (Charlotte Austin), learns from talkative inmate Marge (Tina Carver) that "somebody around here is playing for keeps!" From time to time, the girls hear screams in the night, and always the next day one of them turns up dead from a supposed heart attack. The girls are also afraid of Eric (Friedrich von Ledebur), a tall, cadaverous-looking mute, an assistant to Murdock, who is constantly skulking around the grounds. Carol is skeptical, but when she learns that another young woman has been found dead after a night of screams, she decides to look into the Home's death certificate records. Before she can learn much, she's intercepted by the sour, imperious Mrs. Ford (Ann Doran), one of the Home's senior administrators, who threatens to fire her despite her political connections (Carol is a friend of the Governor's daughter).

|

| The arrogant Dr. Murdock (Victor Jory) questions Carol Adams' (Charlotte Austin) counseling skills. |

As Rogers waits for Murdock in a nicely furnished drawing room, he remarks to Cooper (Paul Cavanaugh), one of the institution's board members, that the painting above the fireplace looks like an authentic Rembrandt. Cooper proudly tells Rogers that he paid a shopkeeper a pittance for the Rembrandt in 1850… "er, 1950 of course," he corrects himself as Murdock, glaring at him, enters the room.

More suspicious than ever, Rogers demands background information on all the staff and decides to do a complete autopsy of Anna, whose body is being kept in the infirmary. Meanwhile, Carol and Rogers find out from Marge, who was in isolation when the rest of the inmates were watching the movie, that she heard screams before the girl was found hanging. "Who screams before committing suicide?" she asks them.

Rogers completes most of the autopsy before the administrative staff, headed by Murdock, comes storming into the infirmary. He lies to them that the autopsy confirms the finding of suicide. Rogers notices that Cooper is the most nervous member of the cabal and seems at odds with his colleagues. He gets him alone in a room to try to pry some information out of him, but is astonished at a couple of extreme biological anomalies-- Cooper's heartbeat can be heard clear across the room, and his skin has become so hardened that not even a sharp knife thrust repeatedly against his hand can break the skin. Cooper tells Rogers that he's arranged for information about the group's secrets to be sent to him in the event of his death or disappearance.

When Cooper turns up missing, Rogers sets out in the middle of the night to dig up a buried diary per Cooper's directions. With the cadaverous mute Eric shadowing him, he finds the diary and learns the deep, dark secret-- that the group had studied under a French expert in "animal magnetism" (?!?) in the 1780s and discovered how to prolong life indefinitely by transferring bioelectric energy from human subjects to themselves. They had found that young women of child-bearing age were the best energy sources (yeah, sure), and that the procedure was always fatal to the donors.

Recently, the group had discovered through Eric's and Cooper's bizarre symptoms that the treatments become less effective over time, requiring ever more frequent applications (and more heart attack victims and suicides at the reform school). Without the energy transference, the heart beats like a kettledrum and the outer layer of skin hardens to the consistency of stone as death approaches.

|

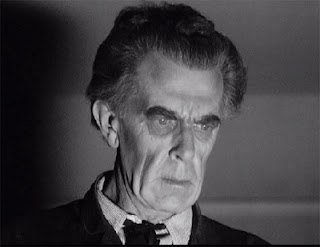

| Eric (Friedrich von Ledebur) visits another unfortunate detention home inmate. |

In 1957, when The Man Who Turned to Stone was released, American popular culture was riding a gnarly youth wave like some blonde southern California surfer dude. Rock and roll was riding high, Elvis was at the peak of his popularity, adults were hunkering down in their living rooms watching westerns like Gunsmoke and Have Gun Will Travel, and teens were flocking to movie theaters and drive-ins to make out while needle-nosed spaceships, atomic monsters, juvenile delinquents, and reform school girls filled the screens in the background.

The Man, with its unique blend of 200-year-old mad scientists and gum-cracking female delinquents, seems to want to appeal to every demographic, and can't quite decide if it's a creepy gothic horror from the 1940s or an up-to-date (for the times) reform school exploitation pic. But then, who am I to question (especially at this late date) the judgment of Sam Katzman, the legendary B movie producer who started out in the film business at the age of 13 as a prop boy, and who by this time had literally hundreds of titles under his belt in every genre (the one common denominator-- they were cheap). 1957 alone saw the release of 8 Katzman pictures, 4 of which where sci-fi/horror (Zombies of Mora Tau - released on a double bill with The Man Who Turned to Stone; The Night the World Exploded; and The Giant Claw, notorious for its ridiculous-looking monster). Only a year earlier, he had produced the underrated The Werewolf, executive-produced Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers, and even more importantly, introduced the first rock and roll movie featuring Bill Haley and the Comets, Rock Around the Clock. Like the Energizer Bunny, Sam kept going and going, producing movies right up to his death in 1973.

Perhaps because of its half-baked blending of gothic horror and teenage delinquent genres, overall mediocre acting, and rock-bottom (even for Katzman) production values, The Man Who Turned to Stone is not nearly as well known as some of his other titles from the '50s. It's not ground-breaking like Rock Around the Clock, doesn't feature a cool monster like The Werewolf, and isn't even unintentionally hilarious like The Giant Claw. The "scariest" effect is tall, skinny Eric with very theatrical-looking pasty skin and dark hollows under his cheekbones for a skull-like appearance. And the premise is weak even for a B movie of this sort-- how in the world did the cabal think they could take over a girl's home and periodically murder the residents without anyone noticing? Healthy young girls having heart attacks? Really?

|

| Uh-oh! This is no spa, and that's not a jacuzzi! |

Also good is Paul Cavanaugh as the anxious, conscience-plagued Cooper. In a nicely realized scene in which the other members of the group condemn Cooper to death for fear he'll spill their secrets ("We decided against your renewal," Murdock coldly tells the dying man), Cooper at first says that he's ready. His next lines are the best in the movie, a warning to his amoral cohorts:

"220 years is too long for any man to live. After a time, you think you're more than a man, you think you can make life… and take life."Good advice not only for arrogant mad doctors, but anyone with power over other people's lives. However, with death just minutes away, Cooper recants his weariness with eternal life and tells the group that perhaps it's a mistake after all for him to die now and possibly lose all the work he's contributed to the project. He rationalizes that if allowed to live, he might be able to find a way to synthesize the energy transference formula so that no one else need die. It's a poignant and well acted scene.

And finally, I will go on record as saying that I both liked and appreciated the unusual ending. Suffice it to say that you will either find it the most preposterous, laughable and anticlimactic ending you've ever seen in a cheap B, or like me, you will find it strangely affecting and very much in keeping with the mindset of these villainous, yet very human, characters. If you're intrigued, check it out!

Where to find it:

Oldies.com

Human monsters hundreds of years old!