Pros: Haunting, character-driven story; Great cast; Excellent widescreen cinematography

Cons: Plot implausibilities and a slow-burn mystery may send some looking for the emergency exits

This post is part of the Aviation in Film blogathon hosted by Rebecca Deniston at her Taking Up Room blog. After you’ve boarded the flight here at Films From Beyond, don’t forget to make connections to the other great flight film posts at the blog hub.

Back in August 2019, I wrote about a couple of TV movies -- The Horror at 37,000 Feet and The Ghost of Flight 401 -- featuring supernatural occurrences on airliners ("Fear of Flying: Special TV Movie Double Feature Edition").

For a lot of people, you don’t need to introduce ghosts or demons to make air travel scary. If you think too hard about it, there’s something unnatural (if not downright supernatural) about taking a 50 ton jet airliner up to 35,000 feet and cruising merrily along at 600 mph. Considering that it’s been a little over the span of a single lifetime since the Wright brothers flew their motorized equivalent of a kite for a few seconds, it doesn’t seem like jet airliners should be possible. (Okay, maybe a Betty White lifetime, but still…)

Covid only added to the ranks of the fear-of-flying club, with many folks reluctant to share a cramped airliner cabin and recirculated air with a hundred other people wearing cheap disposable masks dangling from their chins.

For all the misgivings, air travel remains the safest way to get around. If you’re nervous, but you absolutely, positively have to get there overnight, it’s best to think of other things and board that flight -- the statistics are overwhelmingly on your side.

But whatever you do, don’t screen any of the dozens of airline disaster flicks before your trip. They depict a distressingly large number of ways for a flight to go wrong, each one more heart-stoppingly frightful than the last.

|

| Sit back, relax, and leave the flying to us! |

In just the infamous 1970s Airport series alone, there are mad bombers, hijackers, heat-seeking missiles and mid-air collisions to send fear-of-flying into the stratosphere. The ridiculous culmination of the '70s fascination with air disasters was the made-for-TV SST - Death Flight (1977), which, not content just to feature mechanical problems and a mid-air explosion, upped the ante with a deadly virus outbreak.

Even before the golden age of flight frights, films like No Highway in the Sky (1951), The High and the Mighty (1954) and Zero Hour! (1957) explored more mundane but no less frightening sets of circumstances that could potentially send a multi-ton aircraft plunging to earth. (Zero Hour, with its premise of food poisoning taking out an airliner flight crew and many of the passengers, was hilariously lampooned by Airplane! a couple of decades later.)

It’s one thing when evildoers conspire against us -- where humans are involved, the best laid plans often go astray and the good guys at least have a fighting chance of prevailing.

But when Fate comes calling in the form of a loose fuselage bolt, or an unnoticed computer glitch, or sudden wind shear, or all of the above adding up to a perfect storm of disastrous failure, we start to lose confidence in ourselves and our vaunted technology to keep us safe and secure. We need a convenient scapegoat to restore our faith.

Fate Is the Hunter jettisons the long, nail-biting build-up to disaster of a Zero Hour! or Airport to tell a much more somber story of the aftermath of a tragic crash, and one investigator’s determination to explain the inexplicable and salvage the reputation of his friend, the captain of the doomed plane.

The horrific crash that propels Fate Is the Hunter’s drama is shown in a pre-titles sequence. Captain Jack Savage (Rod Taylor) and Sam McBane (Glenn Ford) are old buddies who flew army transport back in the war, and are now employees of Consolidated Airlines. McBane is a desk jockey working as the airline’s director of flight operations. They exchange pleasantries as Savage gets ready to pilot a routine flight from Los Angeles to Seattle.

|

| Consolidated Airlines flight 22 is getting ready for its rendezvous with Fate. |

Shortly after take-off, one of the plane’s engines catches fire. The ship is still airworthy, but three other planes are in the vicinity, and Savage has to fly a holding pattern while the traffic clears. The crisis escalates as an alarm bell sounds that the plane's only remaining engine is on fire. Savage has no choice but to try to land on a stretch of beach, and almost makes it safely before plowing into a pier. The toll is 53 dead, with only a flight attendant, Martha Webster (Suzanne Pleshette) surviving when she is miraculously thrown clear.

A detailed examination of the wreckage reveals that a seagull got sucked up into one engine, causing it to jam and catch fire. But mysteriously, the other engine is in perfect working order. Webster, who was in the cockpit when everything hit the fan, swears that alarm bells for both engines were going off shortly before the crash, but still suffering from shock, her testimony is discounted.

Savage’s posthumous reputation takes a big hit when a bartender contacts the investigators, saying that Savage was in his bar buying drinks only a couple of hours before the flight. Savage was well-known for his womanizing and hard partying, so the airline executives, wanting to cut their losses, are prepared to pin everything on the captain. Everyone except McBane, who co-piloted transport planes with Savage over the treacherous Himalayan “Hump” route during the war, and knew that under his care-free exterior, Jack was an extremely skilled and responsible pilot.

McBane conducts his own investigation to get to the truth and head off the scapegoating of his friend. In trying to reconstruct Savage’s movements in the last few hours before the flight, McBane interviews several people, all of whom provide important insights into the kind of man Jack was: Lisa Bond (Dorothy Malone), a wealthy socialite and Jack’s fiancée for a short time; Sally Fraser (Nancy Kwan), an oceanographer who came to know the dashing pilot as a tender, compassionate man; Ralph Bundy (Wally Cox), whose life Savage heroically saved during the war; and Mickey Doolan (Mark Stevens), another wartime co-pilot who owed his life to Savage, and later knew him as non-judgmental friend when Doolan became an alcoholic.

McBane, a rational, by-the-numbers sort of guy, is thrown when Sally, a sober scientist, suggests that Fate can explain the seemingly senseless tragedy.

Sally: "…There must be faith attached, the acceptance of a divine operation, a plan."

McBane: "Fifty-three people were destroyed! If you can see the divinity in that..."

Sally: "As I said, there must be faith."

McBane: "Alright, suppose you use that instead of logic, I’m sorry, I can’t."

Sally: "Once you can, so many things will fall into place. It may even occur to you then that Fate has been moving you too."

|

| Sally and McBane reflect on the vagaries of Fate. |

But as McBane delves more deeply into the mystery and prepares to testify before the Civil Aeronautics Board, the bizarre chain of events that contributed to the crash has him coming around to Sally’s way of thinking:

- The type of seagull that got sucked into the engine was normally not found in the area

- Three other aircraft being in the same vicinity at the same time, forcing the crippled airliner into a holding pattern, was a 1 in 1000 occurrence [Note: people in the know report that a crippled plane would always, always, always take landing priority over other air traffic, so this is a problematic plot point.]

- The pier that ultimately caused the aircraft to crack-up and burn had been scheduled to be taken down just days before, but the contractor had decided to go fishing instead

At the hearing, McBane doubles down on the idea that Fate was behind the crash, causing consternation among the board members, the victims’ families and the press. The embarrassed airline executives can’t wait to fire him, but somehow he manages to convince the bigwigs to let him recreate the flight down to the last detail in a last ditch attempt to solve the mystery of the flight’s final moments.

Martha, the sole survivor, is terrified of getting back on board an identical airplane and tempting Fate all over again, but at the last minute agrees to come along to help reconstruct the flight as accurately as possible. It’s a million-to-one shot, but it’s McBane’s only chance to get Fate to show all of its cards and save Savage’s reputation.

|

| It's deja vu all over again for Martha (Suzanne Pleshette). |

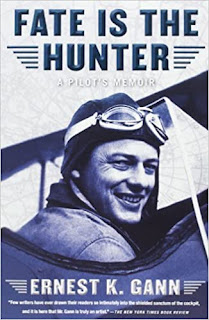

Fate Is the Hunter is only nominally based on the best-selling 1961 book of the same title by Ernest K. Gann. The book is a fascinating account of Gann’s aviation career, piloting commercial passenger DC-2s and DC-3s in the rough-and-tumble 1930s, and then during WWII flying army air transport in the north and south Atlantic and over the infamous “Hump” route across the Himalayas to China.

Gann was an all-American go-getter and renaissance man, a type that has become all but extinct in the 21st century. Before becoming a pilot, he worked as a movie cartoonist and helped make documentary newsreels. He was also an accomplished sailor, and even tried running his own commercial fishing business for a short time. But his biggest fame came as a best-selling author and screenwriter.

By the time that the movie Fate Is the Hunter was released in 1964, six of Gann’s novels had been made into motion pictures, and he had contributed screenplays to five of them. Fate the book, a memoir with numerous anecdotes ranging over several decades, was more of a challenge to turn into a coherent drama.

Gann tried his hand at some early drafts of the screenplay, but the author was so disappointed with the final version, credited to screenwriter Harold Medford, that he asked that his name be removed from the film. He lamented in a later autobiography that this was a bad move, as Fate Is the Hunter played constantly on TV for many years, and by having his name removed he missed out on some healthy TV residuals.

Fate the book is a compelling read. Gann had a knack for sizing up people, especially his fellow pilots, in just a colorful sentence or two. He could also wax eloquent about a profession that was 99.8% boring routine, but then could send your heart in your throat at a moment’s notice. He knew very well that when tragedy strikes, rational people do everything in their power to deny that sometimes, the difference between delivering a plane safely to its destination and crashing it is a matter of sheer luck:“An airplane crashes. There is a most thorough investigation. Experts analyze every particle, every torn remnant of the machine and what is left of those within it. Every pertinent device of science is employed in reconstructing the incident and searching for the cause. Sometimes the investigators wait for weeks until the weather is exactly the same as it was during the crash. They fly exactly the same route in exactly the same kind of airplane and they go to elaborate trouble trying to duplicate the thinking of the pilot, who can no longer communicate his thinking. Often at considerable risk to themselves, the investigators attempt what have been reported as the final tragic maneuvers of the crashed airplane. And sometimes they discover a truth which they can explain in the hard, clear terms of mechanical science. They must never, regardless of their discoveries, write off the crash as simply a case of bad luck. They must never, for fear of official ridicule, admit other than to themselves, which they all do, that some totally unrecognizable genie has once again unbuttoned his pants and urinated on the pillar of science.” [Ernest K. Gann, Fate Is the Hunter, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1961/2011, p 8.]

In spite of Gann’s disappointment, Fate the movie expands on and effectively dramatizes the author’s central thesis.

It’s all there: the inexplicable tragedy, the rush to judgment to explain it away as pilot error, McBane’s lonely crusade to defend Savage’s reputation, the meticulous reconstruction of the flight, and ultimately, awe and wonder at the workings of remorseless Fate.

|

| Lonely is the man who talks about Fate when everyone else wants a rational explanation. |

Whatever you think of the Fickle Finger of Fate premise, the film’s stellar cast helps to sell it as a serious drama instead of cheap melodrama. Glenn Ford is just the right mixture of intense determination in defending his friend’s reputation, and vulnerability as his faith in science and statistics turns to humble acknowledgement of a universe that has its own plans, humanity be damned.

Nancy Kwan has a challenging role as McBane’s philosophy “tutor,” delivering lines that are only a step or two above a carnival fortune teller’s schtick. It doesn’t help that her character is introduced as a Chinese war orphan who was adopted and brought to the States, furthering the hackneyed notion of Asian inscrutability. To the film’s credit, she is also presented as a capable and knowledgeable scientist, an oceanographer, which helps tamp down the banality.

In the flashback scenes, Rod Taylor walks the devil-may-care pilot routine right up to the point of being insufferable, but when called on to interact with honest emotion, he’s very good. Suzanne Pleshette’s role as Martha, the flight attendant and sole survivor, is a relatively small one, but allows for some vivid emoting, from casual banter to pure terror in the pre-titles sequence, to survivor’s guilt when she is interviewed by McBane, and back to terror at the climax when history seems to be repeating itself during the test flight.

Fans of non-stop, pulse-pounding action will want to book a different cinematic flight, but those who go along for the ride will enjoy a great cast at the peak of their games, Oscar-nominated black and white widescreen photography courtesy of Milton Krasner, an evocative music score by Jerry Goldsmith, and a haunting, character-driven story.

|

| McBane is not very appreciative of Savage's rendition of "Blue Moon" as they fly over the Himalayas. |

Where to find it: A very good copy is currently streaming on YouTube (but hurry, that flight could be canceled at any time, and affordable DVD copies are hard to find).