Pros: Nigel Kneale's teleplay is a wrily humorous send-up of Hammer Studios; Features an off-the-wall creation of a peculiar monster

Cons: Plausibility is sacrificed for the convenience of the plot

Yes, I know that the blog title is FILMS From Beyond the Time Barrier, but every once in a while, when the stars and planets are in perfect alignment and broadcast reception is crystal clear, I like to write about the classic TV that has entertained me over the years. Besides which, it’s time for another installment of Terence Canote’s Favourite TV Show Episode Blogathon over at A Shroud of Thoughts. You’ll want to adjust your antenna in order to tune in all the great posts that Terence is hosting this year.

Where would the movies be without that great 20th century innovation known as method acting? We might never have thrilled to Marlon Brando’s signature, anguished cry of Stellaaaa! in his sweaty t-shirt. The only Dean in our collective memory might be that guy named Jimmy who sold sausages on TV, instead of the late, great James Dean. Worst of all, we might never have gotten to know that bottomless well of feelings that is Shia LaBeouf.

From its origins in early 20th century Russian theater, the technique’s creator, Konstantin Stanislavski, could scarcely have imagined how popular it would become thousands of miles away and many years later in America, thanks to the tireless efforts of Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan.

In the hands of Hollywood, this method of fully inhabiting a character’s head has sometimes allowed actors to soar to sublime heights, and almost as often to plumb the depths of ridiculous excess.

One of the most notorious adherents of method acting, Dustin Hoffman, has done both. While making Marathon Man (1976), in which he portrays a NY graduate student caught up in a conspiracy involving Nazi war criminals and smuggled diamonds, Hoffman decided to inhabit his role as completely as possible.

The story goes that when co-star Laurence Olivier asked Hoffman how filming had gone for a scene in which his character was sleep-deprived for days, Hoffman admitted that he had made himself stay up for 72 hours in preparation. To which the classically-trained actor replied, “Why don’t you just try acting?”

A few years later on the set of Kramer vs. Kramer (1981), Hoffman would take it upon himself to make co-star Meryl Streep suffer for her art too. His tactics included abruptly smashing a wine glass to get an unrehearsed reaction, slapping her between takes to increase the tension between their two characters, and reminding Streep of the recent death of her boyfriend to up the emotional intensity of her scenes.

Streep won her first Oscar for the role, and Hoffman was the first person she thanked in her acceptance speech, but it does call into question the ethics of involving others involuntarily in the madness of your method. (Not to mention, smashing wine glasses without warning could put somebody’s eye out.)

|

| "Is it safe?" With Dustin Hoffman on the set, maybe not. |

Speaking of madness in the method, the protagonist of today’s featured episode, the titular “Dummy,” plumbs those depths and then some. In this cleverly constructed story centered on a B movie production, actor Clyde Boyd (Bernard Horsfall), aka “The Dummy,” is having a very bad day on the set of the latest entry in the long running Dummy horror franchise.

It’s bad enough that Clyde has to wear a heavy, cumbersome and stiflingly hot monster suit, but in the middle of an important take, he sees his arch nemesis, actor Peter Wager (Simon Oakes) hanging around the set.

It seems that during a time when Clyde was despairing over his stalled career, Wager started wooing Clyde’s attractive wife, and before long she had left him for the slimy lothario, taking their young daughter with her.

Clyde’s friend, producer “Bunny” Nettleton (Clive Swift), had managed to get financing for yet another Dummy picture, saving Clyde from destitution, but unwittingly also hired the very man who Clyde blamed for stealing his family.

With Wager hanging around, Clyde keeps freezing up and blowing the takes. The pressure is on, because a crucial supporting actor, Sir Ramsey (Thorley Walters), is insisting that after the day’s shooting he’s off to a vacation in the sunny Caribbean, and if the scenes aren’t completed, tough luck.

|

| The problematic graveyard scene in the fictional B movie production, Revenge of the Dummy. |

Bunny is caught in a triangular dilemma with his lead actor having a nervous breakdown, the cause of the breakdown refusing to bow out for the good of the production, and another pompous, selfish supporting actor ready to blow this pop stand to stick his toes in a sandy beach.

When Clyde retreats to his dressing room to start hitting the bottle, Bunny, desperate to get the picture in the can, has to give him the pep talk of his life:

“[Y]ou’re something different Clyde. I don’t think you’ve ever known yourself. You work in another dimension altogether. We never thought about it, we just let it happen. We never talked about it, but we felt it... So did all those other people, all over the world. You don’t need lines written down by other men, other people’s thoughts to repeat… it happens deep down, like going down to the sea, where words don’t function anymore. The rules are different… pressure… perceptivity… awareness… on that level, you reach us.”

Then, when Clyde is ready to once again don the Dummy’s monster mask,

“It’s starting Clyde, can’t you feel it? The power in you? This is it, this is the part I can hardly watch. Oh my god I never wanted to see this, I never wanted to be in this room when you… [pausing for dramatic effect] become the Dummy! I can feel it, I can feel it taking over!”

It’s a rousing halftime football speech and method acting master class rolled into one. Stanislavski couldn’t have done better himself. But unfortunately for Bunny and everyone else on the set, the speech works too well. Powered by a vast reserve of pent-up emotional pain, Clyde actually becomes one with The Dummy, and embarks on a rampage that would make even Dustin Hoffman recoil in horror.

|

| Bunny channels Stanislavski for the benefit of his faltering star. |

Before it’s all played out, a cast member is choked, the police called in, and Clyde’s wife summoned to try to talk him down. And as if things couldn’t get any worse, arch-nemesis Wager is lurking around, itching to use the shotgun he’s retrieved from his car. Can Bunny corral the monster he’s created before someone else gets hurt?

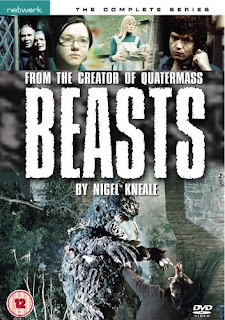

"The Dummy" was one of 6 episodes in an anthology series, Beasts, broadcast in the UK by ITV in 1976. The series was the brainchild of writer Nigel Kneale, a master of sci-fantasy, horror and the macabre. (Mr. Kneale is no stranger to Films From Beyond -- see my reviews of two Hammer film adaptations of his work, The Abominable Snowman and Quatermass 2, and his fascinatingly prophetic dystopian teleplay, "The Year of the Sex Olympics.")

Kneale is best known for his creation Dr. Bernard Quatermass, the crustily courageous scientist whose exploits in several BBC series of the ‘50s thrilled large and enthusiastic UK audiences, and who became even more popular with the Hammer film adaptations (The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass and the Pit in addition to Quatermass 2).

In spite of creating some of the BBC’s most watched series up to that time, all good collaborations must eventually come to an end, and by the mid-'70s Kneale and the BBC had parted ways due to a combination of personal and creative differences.

The year before Beasts, Kneale had scored a success with the ATV production company, penning a creepy folk horror episode, “Murrain” (1975), for their anthology series Against the Crowd. ATV approached him with the idea of writing a whole set of episodes for a thematic anthology series. Kneale proposed exploring the dark, bestial side of humanity through its various relationships with the animal kingdom, and Beasts was born.

As Kneale biographer Andy Murray relates,

“The decision was taken that few animals would actually be seen in the new plays. They would simply be heard, or their presence and influence would be felt, a latent, invisible force. The key to the project, though, was that there would be a great deal of variety between the six plays. ‘That was the first thing that [ATV producer] Nick Palmer and I agreed on,’ Kneale recalls, ‘to make them as different as possible from one another: one would be a funny one, another one horrifying, another one more ordinary.’” [Andy Murray, Into the Unknown: The Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale, Headpress, 2006, p. 126]

Illustrating this variety, in addition to "The Dummy," fan favorites from the series include “Baby,” about a rural veterinarian dealing with superstitious locals who believe that the mummified body of an unidentified animal found in a farmhouse is a witch’s familiar, and “During Barty’s Party,” about a middle-aged couple trapped in their home by a pack of super-intelligent rats.

The animal connection is less direct in “The Dummy,” although the creature suit that Clyde wears is definitely animalistic (not to mention cheap-looking even for a B movie), bringing out his simmering bestial nature at a very inopportune time.

|

| The Dummy gets a final going-over before his big scene. |

While the episode isn’t laugh-out-loud funny, there are farcical elements throughout that elicit the occasional knowing grin. “The Dummy” seems like a comically inappropriate name for a 7-foot-tall monster that is supposed to thrill and terrify audiences, but the character is literally dumb (as in mute), and the actor who animates it has also lost his voice, as it were, through a series of traumatic life set-backs.

Then there’s the duo of Joan Eastgate (Lillias Walker), a journalist covering the making of the latest Dummy movie, and Mike (Ian Thompson), the put-upon studio publicist who tries in vain to prevent Joan from glomming on to the production’s many glitches, foremost of which is the star’s incipient meltdown.

At one point Mike, with barely concealed boredom, rattles off all the films in the Dummy series (which seems to be Kneale's dig at the Hammer horror film cycle that had finally played itself out in the mid-'70s). It’s also a knowing-grin moment for anyone who’s ever rolled their eyes at the film industry's love of sequels:

Joan: “How many have there been?”

Mike: “Dummy films? Six. (Counting on his fingers) Dummy, Horror of the Dummy, Death of the Dummy, Return of the Dummy, and, uh, Dummy and the Devil, Dread of the Dummy, and this one’s a Revenge… a touch obvious in my view…”

|

| Mike almost runs out of fingers trying to count all the Dummy movies. |

Later on, in a conversation with Bunny, Joan becomes a sort of one-woman Greek chorus foreshadowing doom, as she likens Clyde to a ritual dancer wearing a ceremonial mask.

Joan: “It’s not a disguise, they [the tribe] know the man’s inside, but it doesn’t matter. They believe the mask itself is alive, always, all the time, the man is just helping… very deep stuff…”

On the other end of the intellectual spectrum are the other “dummies,” the hopelessly narcissistic supporting actors Wager and Sir Ramsey. Simon Oates does a great job with his deplorable Wager character, oozing contempt for Clyde at every opportunity, while at the same time disingenuously protesting to Bunny that it wasn’t his fault that the man’s wife got fed up with him.

Thorley Walters as Sir Ramsey is the very picture of pompous self-regard, making only the feeblest efforts to appear concerned after a man has been killed and the set is in chaos; you can almost see the wheels turning in his head trying to figure out if the tragedy will affect his vacation plans.

|

| Ramsey and Wager yuck it up as the set of Revenge of the Dummy devolves into chaos. |

Kneale, with dozens of TV and movie projects under his belt by this point, wanted to capture his film industry experience via "The Dummy" episode. Biographer Murray again:

“With a generous helping of barbed humour, Kneale -- who’d always been fond of backstage drama -- was using his own experiences at Bray Studios to satirise the glory days of Hammer. ‘It was staged just like a Hammer film. I’d watched them at it. They were so cosy, these pictures, there was never anything less horrific! But if it had been real and somebody had got accidentally killed, well, that would be a different thing entirely. Not something you’d bargained for.’” [Murray, p. 130]

There are some things about Kneale’s fictional Hammer-lite studio that don’t quite ring true. Clyde has been the man in the monster suit for all the Dummy films, and characters at various times talk about his star quality, but it’s really the suit that’s the star, and seemingly any competent extra could wear the thing. At one point, as Clyde is having his breakdown, Bunny and the director talk about the possibility of replacing him, but dismiss it -- somehow, it wouldn’t be the same without Clyde in the suit. With so much on the line, it doesn’t make much sense.

Regardless, Kneale, with his tongue firmly in cheek, suggests that the so-called “primitive” dancer becoming one with the spirits in his ceremonial mask is not so different from the modern method actor parading around a movie set in his monster suit.

Even if the idea of method actors as shamans seems absurd, “The Dummy” is worth a look, if only for Bunny’s impromptu pep talk. It’s one of the most off-the-wall scenes of a monster being created that you’ll ever see.

|

| Behold, the Dummy! |

Where to find it: Streaming | Complete series