Pros: Creative location shooting and use of repurposed state fair exhibit halls; A fairly unique explanation for its dystopian setting

Cons: Gets bogged down with a lot of pseudo-scientific dialog; Some of the principal actors are as stiff as dept. store mannequins

Many thanks to Barry at Cinematic Catharsis and Gill at Realweegiemidget Reviews for coming up with the Futurethon event and inspiring their fellow bloggers to explore the future through movies. If you haven’t already, check out their sites for links to more cinematic prognostications.

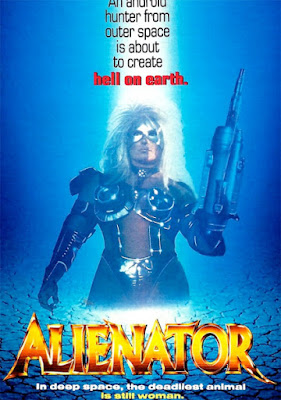

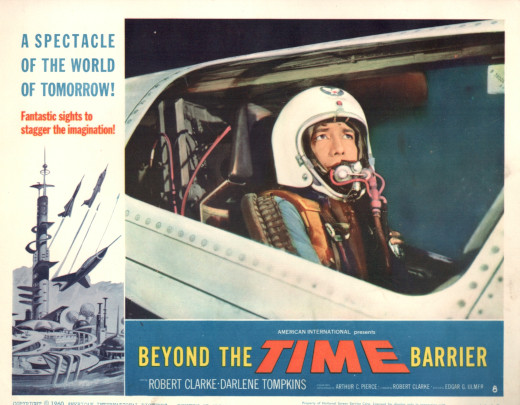

So here I am in the futuristic year 2023, and I’m only now getting around to reviewing the film that provided the name (in part) for this blog. All I can say is that it’s about time. 2024, the year in which Beyond the Time Barrier is set, is almost upon us. If there is even the slightest possibility that the events depicted in the film are prophetic, then there is precious little time to prepare.

As a public service, Films From Beyond is breaking through the time barrier to present our near future as envisioned in the 1960 movie. Are these events highly improbable? Perhaps. Impossible? You be the judge.

Robert Clarke stars as Major William Allison, an Air Force test pilot who has been assigned to fly the X-80 rocket-plane to the edge of outer space. After firing the rocket engine and soaring to an altitude of 100 miles, the plane accelerates uncontrollably, and Allison loses contact with the base.

|

| Put your tray tables up and fasten your seat belts -- 2024 is going to be a bumpy ride! |

Once Allison gets control back and brings the plane in for a landing, he’s amazed to find that the base is completely deserted and in an extremely dilapidated state. Off in the distance he spots the ruins of a city, and next to that, weird structures, including huge towers with blazing lights illuminating the landscape.

As Allison approaches the structures, he’s hit with a paralyzing ray, whereupon figures in radiation suits trundle him off to an underground lair.

The major soon finds that he’s not in Kansas anymore. After being decontaminated in a giant glass enclosure and getting into a shoving match with some guards, he is introduced to the elderly leader known as The Supreme (Vladimir Sokoloff), his second-in-command, the Captain (Boyd “Red” Morgan), and The Supreme’s granddaughter Trirene (Darlene Tompkins).

Allison learns from The Supreme that he is a “guest” at The Citadel, a subterranean complex built as a haven from the hordes of violent mutants that roam the contaminated surface. The Supreme and the Captain are the only members of the Citadel that can hear and talk -- all the others, including Trirene, are deaf mutes as the result of a mysterious plague (although Trirene has the extrasensory ability to read minds). The major is mightily confused, not understanding how so much could have happened in the short time he was aloft in his rocket plane.

|

| "Excuse me, but I seem to have taken a wrong turn at the ionosphere..." |

Allison’s troubles are compounded by the Captain, who is suspicious that he is some sort of spy. The major is thrown into a dungeon reserved for captured mutants, but is released a short time later when Trirene, who has taken a shine to the handsome pilot, convinces her grandfather that he’s no threat.

After gaining The Supreme’s confidence by way of Trirene, Allison is allowed to meet three other “guests” of the Citadel: Gen. Kruse (Stephen Bekassy), Prof. Bourman (John Van Dreelen) and Captain Markova (Arianne Ulmer), who, conveniently, can also hear and talk. It’s this crew that clues the major into the fact that he’s traveled into the 21st century -- 2024 to be exact.

Kruse explains that the notorious plague was caused by radioactive dust from above-ground atomic tests breaking down the atmosphere’s protective layers, allowing deadly cosmic radiation to blanket the earth. Much of the planet’s population was killed off, with most of the survivors ending up either sterile deaf mutes or ravening bald-headed mutants.

Like Allison, all three accidentally broke the time barrier traveling in spaceships that approached the speed of light, and ended up prisoners at the Citadel after crash landing. The Captain, not wanting to let their knowledge and expertise go to waste, put them to work developing a solar energy plant. Markova cattily suggests to the clueless major that his job is now to mate with Trirene, one of the few women left who isn’t sterile.

When the group learns that Allison left his plane at the base intact and ready to fly, their eyes light up. Bourman excitedly explains that there’s a chance that they can send Allison back to 1960, where he can prevent the plague from ever happening. The professor lays out a deceptively simple formula on a chalkboard: take the rocket-plane’s escape velocity and add the velocities of earth’s rotation, its orbit around the sun, and the solar system’s movement through space, and voila!, you’ve got the near-light speed you need to enter the fifth dimension and travel back through time! (Uh-huh...)

|

| "Pay attention class, there's going to be a quiz later." |

Standing in the way of the plan is the paranoid Captain, who has surveillance devices everywhere and is not likely to just sit back and let his prisoner jet off to parts unknown. And then there’s the Kruse crew -- one or more of them may have plans of their own for the plane. Finally, there’s Trirene -- who wouldn’t be tempted to stay put and regenerate civilization with such a special, beautiful girl? (And that doesn’t even take into account the mutants, who are itching to burst from their confines and wreak vengeance on their cruel masters.)

Okay, rather than spoil the ending, let’s see what Beyond the Time Barrier got right about life in the roaring 2020s:

✔ The ruling elites live in luxurious enclaves surrounded by bleak ruins and decaying infrastructure.

✔ Xenophobia runs rampant.

✔ Draconian security measures and omnipresent surveillance keep everyone in line.

✔ The general rule is to shoot your ray gun first and ask questions later.

✔ Society’s undesirables (the mutants) are consigned to poverty and prison.

✔ Much of the population is mute and goes along with whatever the elites say.

✔ A well-meaning but doddering old man nominally rules over the whole mess.

And on the bright side:

✔ Solar power is an up-and-coming energy source.

What it got wrong:

✔ The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963 prohibited all above-ground nuclear tests, which were the cause of Time Barriers’s cosmic radiation plague. (However, the plot point does prefigure the depletion of the ozone layer that became an issue in the ‘70s.)

✔ Interior design predominantly based on the equilateral triangle never caught on.

✔ Jumpsuits that made everyone look like 1950s gas station attendants never became mandatory work attire.

|

| Beyond the Time Barrier also predicted the advent of 5G cell towers... or maybe not. |

The man responsible for Time Barrier's prophecies was Arthur C. Pierce. In addition to Time Barrier, Pierce wrote a number of B sci-fi scripts in the ‘50s and ‘60s, including The Cosmic Man (1959), Invasion of the Animal People (aka Terror in the Midnight Sun, 1959), The Human Duplicators (1965), Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966) and The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966), among others (see my reviews of the first two films here and here).

While Pierce never penned any true sci-fi classics, he had a knack for writing scientific-sounding dialog and tweaking familiar themes in unique ways (i.e., atomic testing degrading the earth’s protective atmosphere). On the downside, Pierce was a bit too enamored with pseudo-science; his movies were often bogged down by characters laboriously mansplaining cracked science concepts (like Prof. Bourman’s chalkboard lecture on time travel and the speed of light).

While working on Time Barrier, Pierce created one very tense, dramatic scene that never made it into the script. In his memoir, Robert Clarke (who produced the film in addition to starring in it) recalled a story conference between the screenwriter and director Edgar G. Ulmer that became overheated:

“One day in the office at General Service Studios, Art [Pierce] turned in the umpteenth rewrite of one particular scene and once again Edgar seemed to be displeased, and he said something that provoked Art. I don’t remember Edgar’s comment, but it was like lighting a firecracker under Art. Edgar was seated at a desk and Art was sitting in a chair, doodling with a long yellow pencil. Something snapped in this poor, tormented writer’s mind: He jumped up out of his chair and leaned across Edgar’s desk and broke the yellow pencil in half right in front of Edgar’s nose. …

It was a very dramatic moment, but later on, one could see the lighter side of it. Art was a conscientious and resourceful sci-fi writer who knew the necessary nomenclature and had done his homework on the technical aspects, but his dialogue wasn’t what Edgar was seeking and finally Art got fed up with Edgar’s goading. … The incident seemed to bother Edgar a little bit; I remember that later on, Edgar in his heavy Hungarian accent referred to Art as ‘This wrrriter who brrreaks his pencil in front of my face!’ But Edgar’s resentment soon passed; he was the type who let everything roll off his back.” [Robert Clarke and Tom Weaver, Robert Clarke: To “B” or Not to “B”, A Film Actor’s Odyssey, Midnight Marquee Press, 1996, p. 202]

No one, especially Ulmer, had time to hold a grudge. Beyond the Time Barrier and The Amazing Transparent Man were shot back-to-back at the same Texas location over the course of only two weeks (neither Pierce or Clarke were involved in the latter production).

These would be the last films Ulmer would direct on American soil. Savvy fans know Ulmer as one of the great B movie directors, with a resume that includes such cult classics as The Black Cat (1934; with Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff), Bluebeard (1944; with John Carradine), Detour (1945; the low budget film-noir masterpiece with Tom Neal and Ann Savage), and The Man from Planet X (1951; also with Robert Clarke).

By the time Time Barrier and Transparent Man rolled around, Ulmer’s best work was behind him. As hinted by the story conference fracas, Ulmer was probably not greatly inspired by Time Barrier's script; he was content to shoot long, plodding scenes of dialog in stationary medium shots and call it a day. On the plus side, the veteran director managed to get his daughter Arianne the part of the duplicitous, femme-fatale-ish Capt. Markova.

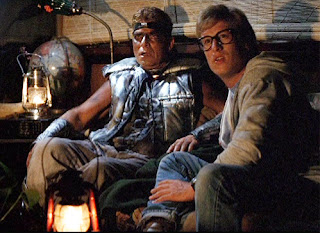

|

| Trirene and Major Allison relax after a hard day listening to incessant technobabble. |

WARNING: SPOILERS ARE LURKING JUST BEYOND THE TIME BARRIER

The film manages to break through the boredom barrier at the climax, when Markova has treacherously let loose the imprisoned mutants and Allison is desperately trying to escape and get back to his plane. In the scenes where the maddened mutants chase down terrified Citadel dwellers, it’s obvious that the bare-bones production could only afford to outfit a handful of mutant extras with ratty clothes and ill-fitting skull caps. The extras are supplemented with mismatched stock footage of scruffy dungeon dwellers from Fritz Lang’s 1959 costume potboiler The Indian Tomb.

But the mutants' screams and shouts as chaos ensues are truly jarring, and you feel sorry for the poor Citadel denizens whose only fault was to blindly (and mutely) follow inept leaders. On top of that, the back stabbing comes fast and furious as various characters jockey to see who gets to ride on the rocket-plane back to their original time period.

For these and other scenes, Clarke and crew made great use of ready-made locations. The futuristic Citadel consisted of structures and exhibits left over from expositions held at Fair Park in Dallas, Texas. Carswell Air Force Base near Ft. Worth stood in for Major Allison’s home base, and a nearby abandoned WWII-era Marine Corps Air Base was utilized for the deserted 2024 ruins. [IMDb trivia]

When Clarke made Beyond the Time Barrier, he was hoping to become a B movie mogul. After appearing in the micro-budgeted sci-fi thriller The Astounding She-Monster (1957), he was astounded by how much money the threadbare production made at the theaters. He told himself he could do even better, and the result was The Hideous Sun Demon (1958), which Clarke wrote, produced, directed and starred in (see my reviews of She-Monster and Sun Demon).

He took a print of Sun Demon to American International Pictures (AIP) in the hopes of securing a multiple picture distribution deal, but was turned down. On the rebound, he signed with a small outfit, Miller Consolidated Pictures, to do Beyond the Time Barrier. It wasn’t long after Time Barrier hit the theaters that the overextended company went under, and ironically, AIP ended up taking over distribution of the picture. After the dust settled, Clarke never saw a dime of profit from either Sun Demon or Time Barrier; all he had to show for his efforts was his $1,000 salary for acting in Time Barrier.

|

| AIP executives hold Robert Clarke hostage while they run off with all the profits from Beyond the Time Barrier. |

But Clarke was nothing if not resilient. In a interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Clarke insisted that he was grateful for his experiences behind the camera:

I would never say I was sorry because if I had not done it, I think I would have been sorry and would be saying that I wish I had tried it. It was an interesting experience. I wish, of course, that it had turned out more profitably and that it had led to other things that would have been more mainstream. With Roger Corman, pictures like these were stepping stones to bigger productions. But I took such a terrible bath with the bankruptcy on both Sun Demon and Time Barrier that I just felt there was no way to make another one and come out with anything. [Tom Weaver, Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers, McFarland, 1988, pp. 90-91.]

If you decide to check out Beyond the Time Barrier, here’s hoping you’re as resilient as Robert Clarke and don’t regret your decision. Because, Prof. Bourman’s theories notwithstanding, most physicists insist that traveling back in time and undoing past actions is impossible.

Where to find it: Streaming #1 | Streaming #2 | DVD