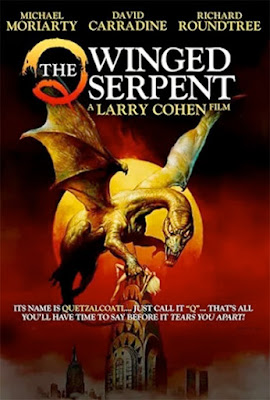

Now Playing: Q: The Winged Serpent (1982)

Pros: Great performance by Michael Moriarty; Upends giant monster movie clichés with creativity and wit.

Cons: Choppy editing gives short shrift to the ritual murder storyline.

Pros: Great performance by Michael Moriarty; Upends giant monster movie clichés with creativity and wit.

Cons: Choppy editing gives short shrift to the ritual murder storyline.

I was very sorry to see that one of my all-time favorite independent filmmakers, Larry Cohen, passed away recently at the age of 77. Larry exemplified the true independent spirit: passionate about his work, inventive, always trying to come up with fresh material, and uncorrupted by big money. Given $100 million, Larry would have preferred to make 100 1 million dollar movies that said something original than 1 blockbuster that served up the same tired old franchise clichés.

As a director Larry never worked with that kind of money, not because he wasn’t talented enough -- he had talent and drive in spades -- but because big money would have compromised his independence and vision. Thankfully, genre filmmaking is all the richer for his insistence on being his own man.

|

| Larry Cohen, 1936 - 2019 |

Q may be off the beaten track even in the sci-fi/horror genres, but in the context of Larry’s career, it’s one of his signature works. Nominally, Q is a giant monster flick about the living embodiment of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, a flying “serpent” that takes up residence in Manhattan and starts feasting on its residents. But Cohen, who was always looking to pour new wine into old genre bottles, upends a bunch of hoary monster movie clichés and creates a very interesting antihero while he’s at it.

The film starts out with a gory scene of an unfortunate window washer who, working high up on the Empire State building, is suddenly decapitated by an unseen thing. NYC detectives Shepard (David Carradine) and Powell (Richard Roundtree) are investigating, and the best they can come up with is that a shard of glass fell from the top of the building and took off the man’s head in a freak accident. Except there are no reported broken windows.

Next, we’re introduced to Jimmy Quinn (Michael Moriarty), a befuddled ex-con and all-around doormat who seems to want to get his life together, but whose worst enemy is himself. He’s a talented pianist, but when he auditions at a local nightclub at his girlfriend’s urging, he messes around to the visible disgust of the proprietor and blows his chance. Jimmy’s back-up plan is to drive the getaway car for his old gang, who are getting ready to rob a diamond retailer.

|

| Q avoids long restaurant lines by plucking her meals from the city's rooftops. |

The professor introduces Shepard to Quetzacoatl, an ancient winged-serpent god that, legend has it, can be summoned by just this sort of ritual sacrifice. Coincidentally, reports start flooding in of a huge monstrosity flying among the skyscrapers, and of wealthy Manhattanites being plucked off the roofs of their luxury condos.

Quinn, the perennial loser, gets himself into another fine mess when he goes along with his buddies on the diamond heist. Despite insisting that he’s only there to drive the car and he doesn’t do guns, his accomplices shove a revolver in his hand and force him to accompany them inside the store. Predictably, shots are fired, chaos ensues, and Jimmy loses the satchel of diamonds as he stumbles into the street and gets clipped by a car.

In a panic he hobbles over to the Chrysler building to look up his lawyer. Finding the office door locked and paranoid that the cops are right behind him, he makes his way up to the deserted tip of the building. At the top of a construction access ladder, he finds to his amazement a large open gash in the structure, and a nest made out of large branches and boards that contains a huge, primeval-looking egg.

|

| "That must be one mighty big pigeon..." |

Cohen’s primary subversion of the standard monster movie formula is to relegate the action-hero stars playing the cops to the margins for much of the movie, while putting the hapless, fidgety Jimmy front and center. While the detectives are standing around scratching their heads over the murders and sightings, Jimmy, in inspired fits, is using his knowledge of the creature’s hideout to get back at his partners in crime and blackmail New York city authorities.

Michael Moriarty, who was relatively unknown at the time, is more than up to the task of carrying the film. By turns he is cocky, sniveling, greedy and clueless. After boasting to his long-suffering girlfriend (Candy Clark) that he led two of his gang buddies to their deaths, he is perplexed by her revulsion. And when he demands from the city authorities a million bucks and exclusive rights to Q’s story in exchange for information about the creature’s lair, he goes from self-pity to “top of the world ma!” egotism in a New York minute.

|

| "Don't make eye contact, it will only encourage him." |

The cops do catch up to the monster at the climax, but in a clever turnaround of the classic King Kong story, they’re the ones holed up at the top of the skyscraper, defending it from the flying monster.

Cohen is also smart to reveal his monster gradually, in stages. At first, we only see a flash of a beak or claw as the torpid, unsuspecting humans are carried away. He intersperses these scenes with subjective, birds-eye shots that glide lazily over even the tallest Manhattan skyscrapers, suggesting god-like omniscience. Then, as the film heads to a climax, we finally see the monster in its entirety, done very competently via stop-motion animation.

|

| "I think it went that way!" |

Later on, Cohen inserts shots of decorative birds and eagles jutting out, gargoyle-like, from the facade of the Chrysler building, as if to suggest that, for all its technology, civilization is not that far removed from superstition and sky-god worship.

In Tony Williams’ book Larry Cohen: The Radical Allegories of a Guerilla Filmmaker (McFarland, 1997), Cohen related how important the Chrysler building was as a location, and the lengths he went to film there:

"[I]t was a perfect location since its feathered structure is bird-like. It also had gargoyles of birds jutting out on all sides. The Chrysler Building was an ideal spot for a giant ‘Q’ to choose for its nest. We could never have afforded to build the pinnacle of the Chrysler Building, so we had to shoot in the actual location. That meant hoisting all the cameras, equipment, and lights, etc., straight up into the tower. The actors had to climb up a very precarious series of ladders … David Carradine actually climbed into the very tip of the needle. It was only wide enough for one person to navigate. He fired his machine gun off from there and the helicopter cameras came as close as possible to get shots of him in action. Apparently, hundreds of people down below in the streets heard the machine-gun fire, and some of them thought an assassination was actually taking place. The New York Daily News is only a few blocks away, and they sent over reporters. They featured us in a front-page story with the headline, 'Hollywood Movie Company Terrorizes New York.'"[p. 396]Larry never let low budgets or bureaucratic obstacles stand in the way of his vision. Although his films are not polished visual spectacles by contemporary standards, they all have an inventiveness, humanity, and subversive wit that many of today’s action and horror films lack. If you’re not acquainted with his work, Q is a great place to start.

Where to find it: Q is available on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as Amazon Prime.