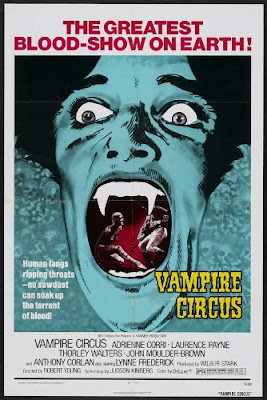

Now Playing: Vampire Circus (1972)

Pros: Adds youthful vitality and a mod visual style to Hammer's standard vampire treatment.

Cons: Too ambitious for its short run time; Some characters and plot lines are not adequately developed.

Pros: Adds youthful vitality and a mod visual style to Hammer's standard vampire treatment.

Cons: Too ambitious for its short run time; Some characters and plot lines are not adequately developed.

Living in southern Nevada, I’ve been lucky to see several magnificent Cirque du Soleil shows based in Las Vegas, including Cirque’s first permanently-located show Mystere, established on the Strip in 1993. From rather humble beginnings as a troupe of street performers hailing from Quebec, Canada, Cirque du Soleil has become a worldwide phenomenon, staging daring visual feasts of sophisticated sets, inventive costumes and awe-inspiring talent.

Cirque du Soleil showcases some of the most extraordinary, gifted acrobats in the world. Their agility, power and grace seem beyond human. You could be forgiven for thinking you’d been transported to another world as they perform amidst Cirque’s wild, surrealistic sets.

In simpler times, more conventional circuses elicited a similar sense of awe and wonder from audiences. Before screens and digital effects completely captured our imaginations, we could still be enthralled by a real, solid, living, breathing fantasy world plopped down in the middle of our dull, prosaic lives.

Since wonder and awe are occasionally companions to fear, writers and filmmakers have occasionally pulled back the circus tent flap to explore its dark side. Ray Bradbury’s classic 1962 novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, about a carnival headed by the sinister Mr. Dark, was originally written up as a movie treatment that failed to gain studio backing. (It would later be made into a 1983 movie starring Jonathan Pryce.)

The 1960s saw a number of films featuring circuses as a backdrop to murder and mayhem, including Circus of Horrors (1960; with Anton Diffring), Circus of Fear (1966; with Christopher Lee), and Berserk (1966; with Joan Crawford).

And then, early in the 1970s, Hammer’s Vampire Circus came to town. While neither Cushing or Lee appear in the film, it makes up for its lack of star power with a copious amount of action and blood crammed into an 87 minute run time.

|

| It's curtains for the Count. |

Fast forward 15 years, and the village is the grip of a mysterious plague, with a multitude of corpses being hauled off in handcarts. The village elders -- the Burgermeister, the schoolmaster and the local doctor among them -- debate whether the plague is supernatural or merely natural in origin. The Count’s curse is definitely in the back of their minds despite the passage of time. Supernatural in origin or not, the state authorities have decided to quarantine the village by force of arms to prevent the contagion from spreading.

Cue the “Circus of Nights,” which rolls into town in spite of the quarantine. The villagers wonder how the circus got through, but are eager for the distraction from their grim problems. An enigmatic gypsy woman (Adrienne Corri) heads up the troupe consisting of a sinister dwarf in clown makeup (Skip Martin), a mute strongman (David Prowse), acrobats, dancers, and an assortment of wild animals including a chimpanzee, a tiger, and a black leopard.

|

| Cirque du Soleil it's not, but the villagers don't seem to mind |

For a film with such a limited budget and minimal sets, there’s more going on than in most three-ring circuses. It’s hard to keep track of everyone and everything without a scorecard: There’s the demonic Count who prefers the blood of young children; his main squeeze, the schoolmaster’s wife; the schoolmaster who leads the rebellion; the grieving father who’s lost his daughter to the vampire; the foppish Burgermeister (Thorley Walters) who welcomes the sinister circus to his village; his daughter, who has a thing for a handsome circus performer who seems to be mysteriously linked to the fearsome panther; the devilish dwarf, who is able to lead all the villagers around by the nose; the mysterious gypsy woman and her silent strongman; the seemingly innocent acrobat couple with amazing shapeshifting powers; the village doctor, who runs off mid-film to evade the quarantine and seek help in the capital city; the doctor’s son Anton (John Moulder-Brown), who is enamored of the schoolmaster’s daughter Dora (Lynne Frederick) , and who together become the prime targets of the Count’s revenge… Got all that?

|

| "Abra-abra-cadabra. I want to reach out and grab ya!" |

Even stranger, when the burgermeister’s daughter Rosa (Christine Paul) becomes infatuated with a handsome young circus member Emil (Anthony Higgins), the mother, after some feeble protests, cheerfully gives her blessing for the young woman to run away with the stranger. While this could be seen as another instance of the mysterious power the circus has over the town, in the context of the scene it just seems ridiculous.

|

| "Tell me, does this blood clash with my lipstick?" |

On the upside, Vampire Circus takes some long standing Hammer conventions -- the 19th century central European setting, the depraved vampire Count, the bevy of beautiful vampire victims and accomplices -- and adds a good deal of vitality to them. The “Circus of Nights” is a nice touch, becoming a sort of surreal play within a play. Its resident vampires are some of the most physical of the Hammer repertoire, adding acrobatic leaps and shapeshifting powers to the usual evil licentiousness.

The Circus’ sideshow attraction, the Mirror of Life, is another interesting addition to all the weirdness. At first it appears to be nothing more than the standard set of funhouse mirrors. But the last and biggest mirror turns out to be a portal through which the vampires can lure victims to their doom.

|

| "Mirror, mirror on the wall, who's the most evil of them all?" |

While the studio went down fighting with their tried-and-true style for such films as Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter (1974) and Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell (1974), they also tried staying relevant by updating their most precious commodity, Dracula. The results were Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972), The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973; both with Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing), and the highly weird horror/martial arts mash-up The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974; with Peter Cushing but minus Lee).

|

| "Now this won't hurt a bit..." |

Ironically, Sir James Carreras, co-founder and then chairman of Hammer Films (and father of the film’s producer, Michael Carreras) reacted to the project with a good deal of skepticism, predicting that “If shot as scripted, 50 percent will end up on the cutting room floor,” and adding, “What’s happened to the great vampire/Dracula subjects we used to make without all the unnecessary gore and sick-making material?” (as related in The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films, Marcus Hearn and Alan Barnes, Titan Books, 2007). He’d no doubt forgotten that many critics had leveled almost identical protests against Hammer’s game changing technicolor horrors, The Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula, years before.

Now, many years later, Vampire Circus stacks up as an eccentric curiosity next to today’s horror output, except perhaps for the fixation on children as victims -- few genre filmmakers of any era have wanted to go down that path. Still, for all its faults and lack of real scares, it’s nonetheless an interesting, stylish film bordering on the surreal.

Where to find it: As of the date of this post, Vampire Circus is available through Amazon Prime.