Now Playing: Diary of a Madman (1963)

Pros: Plays well as either supernatural or psychological horror, depending upon your mood; Price’s mostly understated performance hits just the right note.

Cons: The Horla’s voice sounds more like a mean boss on a bad Monday than a sinister, unearthly creature.

Pros: Plays well as either supernatural or psychological horror, depending upon your mood; Price’s mostly understated performance hits just the right note.

Cons: The Horla’s voice sounds more like a mean boss on a bad Monday than a sinister, unearthly creature.

By the end of his career, Vincent Price had appeared in (or done voice work for) over 200 films and TV shows. Born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1911, he parlayed an upper middle-class upbringing and top-notch education into an early theater success, playing Prince Albert in the hit play “Victoria and Regina” in both London and New York.

In an era when successful stage actors often attracted the attention of Hollywood scouts, Price made the leap into movies, achieving second billing under Constance Bennett in a high society comedy, Service de Luxe, in 1938. While he was active in theater the rest of his life, it’s the movies, especially the B horrors that marked the latter part of his career, for which he’s most famous.

Even in the heady days of the 1940s, before television disrupted the movie industry, there were some early macabre roles that hinted of things to come. In 1940, Price took a turn as the titular character in The Invisible Man Returns (and eight years later provided the voice of the Invisible Man in the gag ending of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein). In the low-budget thriller Shock (1946), he played a wife-murdering physician who attends to the traumatized, mute woman who witnessed the foul deed from her apartment window.

|

| Price as Cardinal Richelieu |

Off camera, Price’s real life was almost as interesting as the characters he played. More than a few of Vincent’s fellow actors and filmmakers have testified that he was the consummate gentleman on the set, always approachable and ready to help.

In between his movie and stage work he managed to pursue a number of passions. He was a renowned art collector and patron, active in such organizations such as the Archives of American Art and the National Society of Arts and Letters. He even partnered with Sears Roebuck & Co. to make original, affordable works of art available in stores via the Vincent Price Collection (he personally curated the collection by making frequent buying trips).

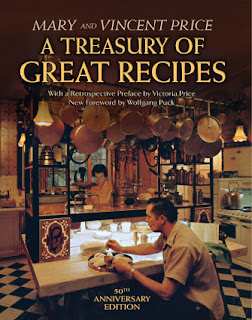

As if that weren’t enough, Vincent was also a noted culinary expert and wine connoisseur. With his wife Mary, he co-authored a lavish cookbook, A Treasury of Great Recipes (1965), which became a bestseller and eventually a collector’s item. His growing gastronomic reputation led to an invitation to be a co-founder of the American Food and Wine Institute, as well an appointment as the international ambassador for California wines. Naturally, the Price’s dinner parties attracted the cream of Hollywood society, politicians, and even a British royal or two. (For more on Price's fascinating life outside of theater and film, see Victoria Price's excellent book Vincent Price: A Daughter's Biography, St. Martin's Press, 1999.)

Perhaps it’s more accurate to say Price made movies and appeared in plays in between living a highly cultured, exemplary life. But being wealthy and refined isn’t always as easy as it seems, especially in the United States. Americans have always been conflicted about high society. They admire great wealth, but are largely put off by intellectuals and connoisseurs of all types who they see as setting themselves above average, hard-working people.

Popular movies naturally reflect the values and biases of the public at large. Ironically, the urbane, sophisticated Price made a very good living portraying refined, worldly characters who were also villainous, corrupt and/or ridiculous.

As Longfellow said, “Whom the gods would destroy they first make mad.” It’s been a long-running tradition that whom the Hollywood gods would destroy, they first make into B-movie madmen. The list of glamorous A-list stars who, as they aged, descended into what must have seemed like the 7th circle of B-movie hell to keep working is a very long one (think Joan Crawford’s last role in the execrable sci-fi/horror pic Trog, or Ray Milland as The Thing with Two Heads).

Price’s advantage when the B movie horror scripts inevitably came flooding in was that he was never a leading man to begin with, and the characters he was used to playing were often unsympathetic. He still played millionaires (House on Haunted Hill, 1959), industrialists (The Fly, 1958 & Return of the Fly, 1959), doctors (The Tingler, 1959; The Abominable Dr. Phibes, 1970) and the usual assortment of princes and nobles (Pit and the Pendulum, 1961; The Masque of the Red Death, 1964; etc.), but the horror genre largely supplanted the historical costume, crime, and romance dramas of his earlier career.

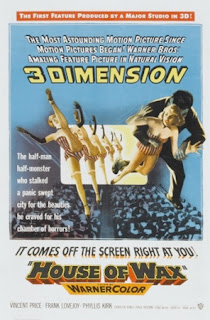

The film that opened up the floodgates was House of Wax (1953), a 3D remake of Lionel Atwill’s 1933 vehicle Mystery of the Wax Museum. In House, Price plays Henry Jarrod, sculptor and proprietor of a failing wax museum, who is horribly injured when his business associate burns down the museum to collect the insurance money. Jarrod rebounds by opening up a new museum of the macabre that is far more commercially successful, but lurking behind the scenes is a madman who has been scarred both physically and psychologically.

Released by Warner Bros. at the beginning of the 3D craze of the early ‘50s, House was wildly successful, raking in over $20 million on a paltry $1 million budget. The film was Price’s sensational horror debut, the equivalent of Karloff’s Frankenstein and Lugosi’s Dracula. It was also one of the few times that Vincent would don horror makeup as the frightfully disfigured Jarrod. Price’s stock-in-trade would become playing characters who were refined and elegant on the outside, but monsters, often mad ones, on the inside.

Diary of a Madman, released a full decade after House of Wax, is typical of the typecasting that dominated Price’s resume after his effective performance as the mad sculptor Jarrod. Diary came smack dab in the middle of a run of low-budget, technicolor Gothic horrors, most from American International Pictures, that solidified Price as a King of Terror in the same league as Karloff, Lugosi, Lee and Cushing. In the several years leading up to Diary, House of Usher (1960), Pit and the Pendulum (1961), and The Raven (1963) had chilled audiences; The Haunted Palace (1963), The Masque of the Red Death (1964), and The Tomb of Ligeia (1964) would soon follow.

Diary came from Admiral Pictures, not AIP, but most horror fans were unlikely to care, given that it ticked off most of the boxes for a scary-good time at the theater. Like the AIP Poe pictures, Diary was shot in gorgeous technicolor on a nothing budget. It tells the tale of a respected French magistrate (or judge if you prefer) who finds himself in the thrall of an invisible evil entity that has the power to take over his will and make him kill.

|

| "I tell you doc, I get this throbbing headache right here, and then everything turns green!" |

The unnerving confrontation with the condemned man soon leads to a series of uncanny incidents that have Cordier doubting his sanity. Trying to relax in his study, he is alarmed to see that a photograph of his dead wife and child is hanging next to the fireplace. He interrogates his manservant, who has no idea how the portrait got there. Returning it to a trunk in the attic, Cordier is again alarmed when he walks over to look at a bust of his wife, and finds the words “Hatred is evil” written in the heavy dust in front of the sculpture -- words that Girot had uttered just before attacking him. When he tries to show the writing to the manservant, he’s shocked to find that it has completely vanished.

The high strangeness culminates back at Cordier’s court offices, where he finds that the file containing Girot’s trial testimony has mysteriously appeared on his desk. Suddenly, a bottle of ink turns over onto the papers as if tipped by an invisible hand. Cordier hears disembodied, evil laughter, then collapses in his chair as a voice menacingly tells him, “You deprived me of Girot’s body, his mind, his will… now I will have yours!”

Fearing for his sanity and unable to continue with his magistrate duties, Cordier retreats home. He makes a visit to the doctor, who dismisses the idea that he is going mad. The doctor prescribes a change of lifestyle, advising him to reconnect with the art world and take up sculpting again, which he enjoyed when his wife was still alive.

|

| Cordier, Odette, and Odette's bust (okay, I know what you're thinking - get your mind out of the gutter!) |

Cordier agrees, unaware that Odette is the painter’s wife. She is none too happy that her husband (Paul Duclasse, played by Chris Warfield) is struggling and selling his paintings too cheaply, and sees an opportunity to get some money out of the wealthy magistrate.

Over the course of the next several weeks, Cordier is rejuvenated as Odette sits for him. He’s had no more visits from the malevolent entity, and is beginning to think it was all a bad dream as he becomes more and more enamored by Odette.

The relationship becomes so cozy that, in an unguarded moment, he admits to Odette that his wife committed suicide. The admission seems to have triggered something: after Odette leaves the studio, the invisible entity barges back into the good magistrate’s life like an avenging angel (or demon).

In a theatrical voice dripping with contempt, it introduces itself as a Horla, a member of a race of beings that exist on a parallel plane of existence, but who can be brought into the human plane through acts of human evil. When Cordier protests that he has always fought evil, the Horla accuses him of murder-- he blamed his innocent wife for the death of their son and drove her to suicide.

“Now I am here and will never leave you,” the Horla declares. Through Cordier’s unacknowledged evil acts, he has surrendered his will to the malevolent entity. With the Horla seemingly in control, the once respectable magistrate starts down the road to perdition.

|

| "Where are you, you wascally Horla!" |

The Horla tells Cordier that Paul must die, but Cordier resists. Ominously, a huge vase in the mansion’s entryway falls as Paul makes his exit, narrowly missing him. This is only the first incident in a grim series that will result in murder, mutilation, and attempted murder.

Somewhat like the Horla itself, there is a less visible movie -- one of subtler psychological horror -- lurking in the shadows behind what appears to be straight-out horror. On the surface, Diary of a Madman hits viewers over the head with the idea of a very real, yet invisible monster.

At the film’s end, as Cordier’s associates are trying to make sense of his diary, the manservant insists, “he was ill for so long, the insanity grew worse, he didn’t know what he was doing!” The estate executor turns to the priest with a half-question -- “this Horla, it was in his imagination of course…” -- to which the priest responds, “can it be denied that evil exists, or that it can possess a man?”

|

| "Dang! Cordier only left me his toaster oven and this stupid diary!" |

Cordier has just finished presiding over an arduous capitol murder trial and sentenced a man to death -- one who attacks him in his jail cell after making one last desperate tempt to proclaim his innocence. This opens up a Pandora’s box of unpleasant memories, manifested by the portrait of his wife and son that mysteriously shows up in his study.

Cordier’s studio with its dust-covered reminders of a previous life is a perfect metaphor for the magistrate’s unconscious repression of his own guilt. The writing in the dust that is there and then suddenly isn’t -- “Hatred is evil” -- is a warning from that unconscious.

Vivacious, flirtatious Odette seems to promise new life and new love, and it’s just at this point, where Cordier’s hope is greatest, that the Horla, like a monster from the Id, rises up with a vengeance. The entity takes the portrait of Cordier’s dead family out of its dusty trunk and hurls it at him, accusing him of murder by mental cruelty. Perhaps worse yet, the Horla uses its invisible hands to rework the clay of Odette’s sculpture from a laughing beauty to the visage of a malicious, calculating shrew. Despite Cordier’s weak protestations, the verdict is severe: his past is a lie, as is his future; he has become a condemned prisoner of his own guilty mind.

After Paul Duclasse’s visit, Cordier knows there is no future with the gold-digging Odette, but she has awakened hope and yearning (and the Horla) in him, and for that she has to die. At this point, Diary pays gruesome homage to Price’s memorable role in House of Wax. With no recollection of following Odette to her apartment and stabbing her, he is shocked by the morning paper’s headline that her headless corpse has been found.

|

| It's deja vu all over again: Price does his familiar mad sculptor bit. |

Paul Duclasse is arrested for the murder on the testimony of witnesses who saw him arguing with his wife shortly before the crime. Cordier at first denies having known Odette or Paul, but when he is scheduled to preside at Paul’s trial, his conscience gets the better of him, setting up a final confrontation with the Horla (or his unconscious, or both -- you make the call).

Price is excellent as the prominent, respected man haunted by his past and an invisible entity that won’t let him forget it. In an interview conducted years after the film’s release, director Reginald Le Borg paid Price something of a backhanded compliment. When asked if Price had any enthusiasm for the role or if it was just another job for him, Le Borg responded,

"It was just another job for him. But he did become conscious that I was holding him down. I had looked at some of his other pictures, and I thought he overacted in some. On Diary of a Madman I held him down -- he started to gesticulate and raise his voice in some scenes, and so I took him aside and whispered, ‘Tone it down, it’ll be much more effective that way.’ He did, and he thanked me very much afterward." [Tom Weaver, Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers, McFarland, 1988, p. 246]In the same interview, Le Borg also addressed one of the more problematic aspects of the film -- the Horla’s voice:

"I felt that the story was a good one and it came out very well -- except for the voice of the Horla, which I wanted to distort quite a bit. We made a test of the voice, the way I wanted it, and [producer] Eddie Small said, ‘I can’t understand a word!’ He wanted the Horla to speak normally, which was wrong." [Ibid., p. 245]Wrong is something of an understatement. The Horla, performed by Joseph Ruskin, sounds like a game show announcer trying to be sinister, and goes a long way to undoing the carefully crafted aura of uncanny dread.

|

| "Hey, what's with all that clay you've been bringing home on your clothes?" |

On the plus side of the ledger is Nancy Kovack’s performance as Odette. In addition to being scheming and flirtatious, Odette is also vivacious in a way that goes beyond mere good looks. She is happy and healthy and enjoys the company of men. Even as she’s throwing over her poor, struggling artist husband for the wealthy and respectable Cordier, you can still sympathize with her, at least a little -- girls like Odette just want to have fun, and she was unlucky to be born in the wrong era.

While Diary is not up there with the best of Price’s Gothic horrors, it’s a solid B production, competently (if somewhat stodgily) directed, beautifully shot by cinematographer Ellis W. Carter, and featuring some good performances. Unfortunately, debuting in the middle of Price’s run of highly acclaimed and profitable Edgar Allan Poe pictures for AIP, it got somewhat lost in the shuffle. But the Horla still lives on in digital streams and on DVD.

Where to find it: try here for the DVD; and for the moment, it’s also streaming on Youtube.

Epilogue: Fittingly for such a creature, the Horla seems to have been born out of real tragedy. Guy de Maupassant, “father of the modern short story,” was famous for his clever plots and keen insights into psychological states. He influenced a number of great writers, including Somerset Maugham, Henry James and O. Henry. A lover of solitude, later in life he developed a paranoia complex that was no doubt aggravated by the syphilis that he contracted as a young man. A few years after writing The Horla he tried committing suicide, and died in a private asylum in Paris in 1893.

In his article for Mysterious Universe, “Famous Writers and their Bizarre Paranormal Experiences,” Brent Swancer relates Maupassant’s tortured state of mind in his last years:

In his article for Mysterious Universe, “Famous Writers and their Bizarre Paranormal Experiences,” Brent Swancer relates Maupassant’s tortured state of mind in his last years:

"[T]owards the end of his life [Maupassant] claimed that he had frequently been visited by his doppelgänger, who would often talk and interact with him. One day, things took a sinister turn when de Maupassant was sitting at work writing a story called The Horla, when his doppelgänger had apparently entered the room, calmly taken a seat next to him, and begun dictating what the author was writing until the unnerved man called to his servant in a panic and the double vanished. Bizarrely, this particular story he had been working on is about a man being haunted by an evil entity that plans to turn him insane and take over his body. Almost prophetically, Maupassant is said to have gradually lost his grip on sanity in the years after finishing the story. As his mental state further deteriorated, Maupassant was allegedly visited by his doppelgänger again, with the entity sitting in his room and burying its face in its hands as if in abject despondency. Maupassant would later be admitted to an insane asylum, where he would eventually die around a year after this weird last encounter, perhaps with thoughts of the doppelgänger still dancing through his head. Maupassant would write about his doppelgänger experience in his short story Lui."

No comments:

Post a Comment