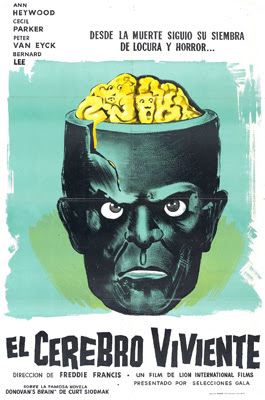

Now Playing: The Brain (1962)

Pros: Interesting melding of a crime thriller with sci-fi; Dark and moody with eccentric characters

Cons: Wooden acting by the lead; Straight-up sci-fi / horror fans will be disappointed

Pros: Interesting melding of a crime thriller with sci-fi; Dark and moody with eccentric characters

Cons: Wooden acting by the lead; Straight-up sci-fi / horror fans will be disappointed

I'm not sure why, but lately I've been on a living head / living brain kick. A few months ago I did a quick survey of the curious "living head" sci-fi subgenre of the '50s and '60s. Before that, I wrote about the greatly under-appreciated The Colossus of New York (1958), wherein a brilliant scientist has his brain transplanted into a robot body, resulting in some unexpected -- and cheesily fun -- consequences.

Not to keep beating a dead horse, but as science and cybernetics grind relentlessly toward that day when we can finally preserve the brain (or our living consciousness) outside of these shells we call bodies, perhaps we need to revisit that ancient mind-body debate -- what is it that truly makes us… us? Is the core of our being in the brain, with all the electrical activity that produces conscious thought (and that unique personality that is all you), or is there more to us than just that one, albeit very vital, part? Is the body also an essential part of what is you? What about the soul? Does it even exist? If it does, does it need a body? Laugh at moldy old B movies like Colossus and The Brain That Wouldn't Die all you want, but they actually attempt to address these issues in offbeat and entertaining ways.

The obscure UK-German co-production The Brain (1962) presents its own quirky take on this existential subject in its relatively spare 83 minute run time. The Brain (and its source novel, Donovan's Brain by Curt Siodmak) posits that, just as nature abhors a vacuum, the living brain abhors being bodiless. So much so, that, given time, it will develop frightening telepathic and telekinetic powers to procure the needed body. After all, what good is pure thought without the physical means to back it up? And if that pure thought just happened to belong to a powerful, implacable multimillionaire used to having his own way, you can imagine how pissed he'd be to find himself reduced to a mass of brain matter plopped into a glass jar with some electrodes attached.

In Siodmak's original 1942 novel and the best-known film adaptation, Donovan's Brain (1953; with Lew Ayres, Gene Evans and Nancy Davis), Donovan is a monster who uses his telepathic powers to carry on with his evil deeds and eliminate his enemies. The Brain (and an earlier predecessor, The Lady and the Monster, 1944) takes a different tack, wherein the disembodied magnate exercises mind control to investigate his own murder and right some wrongs (or at least that's what I gather from the synopsis -- I've never seen the 1944 adaptation).

|

| "I ain't got no body..." |

Just as Holt begins dictating into a tape recorder, we see an exterior shot of the plane, and an explosion. Cut to the crash site, where Doctors Peter Corrie and Frank Shears (Peter van Eyck and Bernard Lee, respectively) are inspecting the scene for survivors. It seems their research lab, where they've been doing some interesting work with monkey brains, is nearby, and naturally they've been called out to the site to help (never mind that after a mid-air explosion and crash, there wouldn't be much left to help with).

Miraculously, there's enough left of Holt to scrape up and take back to the lab -- but no time to take him to the hospital (uh-huh). Just as Corrie and Shears are ready to pronounce the financier dead, they spot evidence of brain activity. The somewhat-less-than-ethical Corrie is excited by the prospect of finally being able to experiment with a human brain, while at the same time saving a life (in a manner of speaking). He persuades his decidedly reluctant surgeon colleague to help him extract the brain from Holt's completely broken and rapidly fading body. Little does he know that he'll soon be in the employ, so to speak, of the determined rich man who refuses to die.

Corrie devises a system that activates a light over the tank whenever Holt's brain is "awake." "Every thought has it's own signature," he tells his beautiful lab assistant Ella (Ellen Schwiers). That night, Corrie can't sleep. He wanders downstairs, seemingly lost in thought, and pauses over the tank holding Holt's brain. As he shuffles away in the darkened room the brain-activity light comes on, eerily illuminating the disembodied grey matter floating in the tank. Corrie soon finds himself at his desk, pondering the microphone from Holt's dictation machine that was recovered from the crash. He starts to write on a sheet of paper, but then switches the pen from his right hand to his left!

|

| "You took his brain... what will they say when they dig him up again?" |

Although it was filmed in England and more than half the cast is British, this dark, moody British-German co-production is more reminiscent of the Dr. Mabuse and Edgar Wallace crime thrillers ("krimis") that were so popular in Germany in the 1960s. Peter van Eyck in the lead role of Corrie/Holt gives The Brain a decidedly Teutonic tilt: he played in several of the Dr. Mabuse films of the 1960s, including The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), Dr. Mabuse vs. Scotland Yard (1963), and The Secret of Dr. Mabuse (1964). Unfortunately, van Eyck is pretty wooden throughout the film, thus undercutting the menace and intrigue of a character in the grip of a powerful telepathic brain. James Bond fans will immediately recognize Bernard Lee in the Frank Shears role -- that very same year he would appear as 'M' in the first Bond movie, Dr. No (and reprise the role in 9 more Bond films after that).

|

| You'd better do everything this man tells you to -- telepathically or not! |

Martin: I became a painter, because I couldn't think of anything that would annoy my father more.Freddie Francis, the Oscar-winning cinematographer turned horror and sci-fi film director, keeps things moving nicely in a shadowy, "Dr. Mabuse meets Donovan's Brain" fantasy world. Not long after this film, he directed a couple of decent psychological thrillers for Hammer, Paranoiac (with Oliver Reed, 1963) and Nightmare (1964). He also had a go at both Frankenstein and Dracula for Hammer (The Evil of Frankenstein, 1964 and Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, 1968). In addition, he directed some of the better Amicus horror anthologies, including Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965) and Tales from the Crypt (1972). (See also my post on another of Francis' creepy directorial outings, The Creeping Flesh, 1973.)

Corrie: Did you succeed?

Martin: Oh yes, I succeeded. I wanted to be as unlike him as I possibly could. He was a great, busy beast of prey… so I decided to be innocently useless.

I won't go so far as to say that if you see just one adaptation of Siodmak's Donovan's Brain, this should be it. But if you're a fan of the dark, film-noirish German "krimis," your brain will thank you for tracking it down.

Where to find it:

Trash Palace (Rare Sci-fi and Fantasy Movies)

Amazon Instant Video

No comments:

Post a Comment